This year’s Cannes Classic sidebar has one or two priceless gems glittering in its antique crown. Apart from well-known legends: Ozu’s Tokyo Story, Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Wilder’s Apartment, Varda’s One Sings, The Other Doesn’t and Bondarchuks’ War and Peace, there are some worthwhile lesser known features not be missed.

This year’s Cannes Classic sidebar has one or two priceless gems glittering in its antique crown. Apart from well-known legends: Ozu’s Tokyo Story, Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Wilder’s Apartment, Varda’s One Sings, The Other Doesn’t and Bondarchuks’ War and Peace, there are some worthwhile lesser known features not be missed.

To start with, there is Henry Decoin’s Beating Heart from 1940, a fitting tribute to leading star Danielle Darrieux, who died last year aged 100. The couple were married while filming this screwball comedy, which was remade in Hollywood in 1946. Darrieux plays Arlette, a young girl running away from a reform school, only to join a school for pick-pockets, run by a Fagin-like character. He instructs her to steal an ambassador’s watch, but Arlette falls in love with him. Like in most of Decoin’s well-structured films, the tempo plays a big role. Decoin was often overlooked as a director, largely because of his rather uneven output, but his post-war noir masterpieces like La Chatte (1958) are really stunning.

Jacques Rivette is famous for his playful features such as Céline and Juliette go Boating, but his one and only excursion into mainstream, La Religieuse (1966), based on a Diderot novel, is full of anarchic fun. Suzanne Simonin (Anna Karina), is incarcerated in a cloister against her will, and soon falls foul of not one, but three Mother-Superiors: they treat her sadistically, tenderly, or as an object for plain lesbian lust – but Suzanne stays pure. This anti-clerical romp was very popular at the box office, and served as a liberating force for Karina who finally got a divorce from JL Godard after having acted in their final collaboration, Made in USA, in the same year.

Jacques Rivette is famous for his playful features such as Céline and Juliette go Boating, but his one and only excursion into mainstream, La Religieuse (1966), based on a Diderot novel, is full of anarchic fun. Suzanne Simonin (Anna Karina), is incarcerated in a cloister against her will, and soon falls foul of not one, but three Mother-Superiors: they treat her sadistically, tenderly, or as an object for plain lesbian lust – but Suzanne stays pure. This anti-clerical romp was very popular at the box office, and served as a liberating force for Karina who finally got a divorce from JL Godard after having acted in their final collaboration, Made in USA, in the same year.

Hyenas (1992), directed by Senegalese filmmaker Djibri Diop Mambety (1945-1998), is a re-telling of the Durrenmatt play ‘Der Besuch der alten Dame’ (Visit of an old Lady). Set in an impoverished African village, the old lady in question is very rich – but she has not forgotten how her lover (now the Mayor) had treated her when she was pregnant with his child. She asks the townsfolk a simple question: do they want to participate in her wealth and punish the guilty man, or would they prefer clean hands and poverty. Colourful and very passionate, this adaption of a Swiss play works very well in its African setting.

Hyenas (1992), directed by Senegalese filmmaker Djibri Diop Mambety (1945-1998), is a re-telling of the Durrenmatt play ‘Der Besuch der alten Dame’ (Visit of an old Lady). Set in an impoverished African village, the old lady in question is very rich – but she has not forgotten how her lover (now the Mayor) had treated her when she was pregnant with his child. She asks the townsfolk a simple question: do they want to participate in her wealth and punish the guilty man, or would they prefer clean hands and poverty. Colourful and very passionate, this adaption of a Swiss play works very well in its African setting.

Diamonds of the Night. Adapted from a short story by Arnošt Lustig, Diamonds in the Night follows two boys (Ladislav Jánsky and Antonín Kumbera) on the run through the forest after escaping a train taking between concentration camps. Showing in the Cannes Classics sidebar, it tributes the Czech New Wave director Jan Nemec whose concept of “pure film”, urged audiences to relate their own experience to the ephemeral fractured narrative he masterfully puts together in this cinematic wartime escape drama..

Youssef Chahine (1926-2008), Egypt’s most famous director, was very critical of radical elements of the Muslim faith. Destiny (1997) is set in the 12th century in the Spanish province of Andalusia, then ruled by Muslims. The Caliph appoints the liberal philosopher Averros as a high court judge. But his wise and humane judgement become the butt of criticism by a group of radical Muslims, who want to banish the Caliph, using Averros as a means to and end. After a long inner struggle, the Caliph sends the philosopher into exile, but the radicals lose out: Averros’ rule of law has gained popularity all over the province. Chahine, as always, directs with great sensibility, and a brilliant use of colour.

Finally, there is La Hora de los Hornos (The hour of the Furnace) from Fernando Solanas, a documentary which could only be shown in his homeland of Argentina in 1973, five years after its premiere in 1968. Exploring a central theme of worldwide insurrection, from student unrest in the USA to Czech resistance against the Soviet invasion, Solanas paints a picture of an utopian liberation. Even Argentina, which never really had the slightest hope of a proper democracy – never mind a revolution – is shown as ripe for revolution on behalf of the working masses. Running for over four hours, La Hora is a document of hope, well-structured, passionate and idealistic – but unfortunately overtaken by a grim reality. Still, it is a worthwhile, monumental effort. AS

THE FULL CLASSICS LINE-UP

Beating Heart (Battement de cœur) by Henri Decoin (1939, 1h37, France)

2K Restoration presented by Gaumont in association with the CNC. Image works carried out by Eclair, sound restored by L.E. Diapason in partnership with Eclair.

Ladri di biciclette (Bicycle Thieves by Vittorio De Sica (1948, 1h29, Italy)

Presented by Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna, Stefano Libassi’s Compass Film and Istituto Luce-Cinecittà. Restored by Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna and Stefano Libassi’s Compass Film, in collaboration with Arthur Cohn, Euro Immobilfin and Artédis, and with the support of Istituto Luce-Cinecittà. Restoration carried out at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory.

Enamorada by Emilio Fernández (1946, 1h39, Mexico)

Presented by The Film Foundation. Restored by UCLA Film & Television Archive and The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project in collaboration with Fundacion Televisa AC and Filmoteca de la UNAM. Restoration funded by the Material World Charitable Foundation. The film will be introduced by Martin Scorsese.

Tôkyô monogatari (Tokyo Story / Voyage à Tokyo) by Yasujiro Ozu (1953, 2h15, Japan)

Tôkyô monogatari (Tokyo Story / Voyage à Tokyo) by Yasujiro Ozu (1953, 2h15, Japan)

Presented by Shochiku. Digital restoration by Shochiku Co., Ltd., in cooperation with The Japan Foundation. For the 4K restoration, the duplicated 35mm negative was provided by Shochiku, managed by Shochiku MediaWorX Inc. and conducted by IMAGICA Corp. French distribution in theaters: Carlotta Films.

Vertigo by Alfred Hitchcock (1958, 2h08, United States of America)

Vertigo by Alfred Hitchcock (1958, 2h08, United States of America)

Presented by Park Circus. 4K digital restoration from the VistaVision negative done by Universal Studios. The film will be screened at the Cinéma de la Plage (Movies on the Beach).

The Apartment by Billy Wilder (1960, 2h05, United States of America)

Presented by Park Circus with the co-operation of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. 4K digital restoration from the original camera negative. Digital restoration completed by Cineteca di Bologna, Colour Grading by Sheri Eissenburg at Roundabout in Los Angeles. Supervised on behalf of Park Circus by Grover Crisp.

Démanty noci (Diamonds of the Night) by Jan Němec (1964, 1h08, Czech Republic)

Presented by the National Film Archive, Prague. The restoration was done by the Universal Production Partners studio in Prague, under the supervision of the National Film Archive, Prague.

Voyna i mir. Film I. Andrei Bolkonsky (War and Peace. Film I. Andrei Bolkonsky)

by Sergey Bondarchuk (1965, 2h27, Russia)

Presented by Mosfilm Cinema Concern. Digital frame-by-frame restoration of image and sound from 2K scan. Producer of the restoration: Karen Shakhnazarov.

La Religieuse (The Nun)

by Jacques Rivette (1965, 2h15, France)

Presented by Studiocanal. 4K restoration from the original camera negative. Sound restauration from the sound negative (only matching element). Works carried out by L’immagine Ritrovata laboratory under the supervision of Studiocanal and Ms. Véronique Manniez-Rivette with the help of the CNC, the Cinémathèque française and the Fonds culturel franco-américain.

Četri balti krekli (Four White Shirts)

Četri balti krekli (Four White Shirts)

by Rolands Kalnins (1967, 1h20, Latvia)

Presented by National Film Centre of Latvia. 4K Scan and 3K Digital Restoration from the original 35mm image internegative and print positive materials mastered in 2K. Restoration financed by the National Film Centre of Latvia, the restoration made by Locomotive Productions (Latvia). Director Rolands Kalnins in attendance.

La Hora de los hornos (The Hour of the Furnaces)

by Fernando Solanas (1968, 1h25, Argentina)

Presented by CINAIN – Cinemateca y Archivo de la Imagen Nacional. 4K Restoration from the original negatives, thanks to Instituto Nacional de Cine y Artes Audiovisuales (INCAA), in Buenos Aires. With the supervision of director Fernando “Pino” Solanas. French Distribution: Blaq Out. Fernando Solanas in attendance.

Specialists / Gli specialisti)

by Sergio Corbucci (1969, 1h45, France, Italy, Germany)

Presented by TF1 Studio. Full version previously unseen restored in 4K from the original Technicolor-Techniscope image negative and French and Italian magnetic tapes by TF1 Studio. Digital work carried out by L’Image Retrouvée laboratory, Paris / Bologne. French theater distribution: Carlotta Films. The film will be screened at the Cinéma de la Plage (Movies on the Beach).

João a faca e o rio (João and the Knife)

João a faca e o rio (João and the Knife)

by George Sluizer (1971, 1h30, the Netherlands)

Presented by EYE Filmmuseum, Stoneraft Film in association with Haghefilm Digital. A full 4K restoration of the original 35mm Techniscope camera negative shot by Jan de Bont. By bypassing the originally required analogue blow up to Cinemascope, this digital restoration presents a direct-from-negative colour richness and image sharpness never seen before.

Blow for Blow

by Marin Karmitz (1972, 1h30, France)

Presented by MK2. Restoration carried out by Eclair from the original negative in 2K with the help of the CNC and supervised by director Marin Karmitz. The film will be re-released in French movie theaters on May 16th, 2018. Marin Karmitz in attendance.

L’une chante, l’autre pas (One Sings the Other Doesn’t)

L’une chante, l’autre pas (One Sings the Other Doesn’t)

by Agnès Varda (1977, 2h, France)

Presented by Ciné Tamaris.

The film will be screened at the Cinéma de la Plage (Movies on the Beach) with Agnès Varda in attendance.

2k digital restoration from the original negative and restoration, color grading under the supervision of Agnès Varda and Charlie Van Damme. With the support of the CNC, of the fondation Raja, Danièle Marcovici & IM production Isabel Marant, with the support of Women in Motion / KERING. International Sales MK2 films. Distribution in theaters: Ciné Tamaris (the film will be released in France on July, 4th, 2018).

Grease

by Randal Kleiser (1978, 1h50, United States of America)

Presented by Park Circus and Paramount Pictures. 4K digital restoration from the original camera negative. The film will be screened at the Cinéma de la Plage (Movies on the Beach) with John Travolta in attendance.

Fad,jal

by Safi Faye (1979, 1h52, Senegal, France)

Presented by the CNC and Safi Faye. Digital restoration carried out from the 2K scan of the 16mm negatives. Restoration made by the CNC laboratory. Safi Faye in attendance.

Five and the Skin (Cinq et la peau)

Five and the Skin (Cinq et la peau)

by Pierre Rissient (1981, 1h35, France, Philippines)

Presented by TF1 Studio. 4K restoration from the original camera negative and the French magnetic tape by TF1 Studio with the support of the CNC and the collaboration of director Pierre Rissient. French distribution in theaters: Carlotta Films. Pierre Rissient in attendance.

A Ilha dos Amores (The Island of Love)

by Paulo Rocha (1982, 2h49, Portugal, Japan)

Presented by Cinemateca Portuguesa – Museu do Cinema. 4K wet gate scan of two 35mm image and sound interpositives struck in a Japanese film lab in 1996. Digital grading was made by La Cinemaquina (Lisbon, Portugal) using a 35mm distribution print from 1982 as a reference. Digital restoration of the image was made by IrmaLucia Efeitos Especiais (Lisbon, Portugal).

Out of Rosenheim (Bagdad Café)

by Percy Adlon (1987, 1h44, Germany)

Presented by Studiocanal. 4k Scan and restoration. Work led by Alpha Omega Digital in Munich and carried out under the continuous supervision of director Percy Adlon. Original negative, kept in Los Angeles in excellent condition, processed in Munich for scanning and image by image restoration. The film will be screened at the Cinéma de la Plage (Movies on the Beach) with Percy Adlon in attendance.

Le Grand Bleu (The Big Blue)

by Luc Besson (1988, 2h18, France, United States of America, Italy)

Presented by Gaumont. A 2K restauration. Image work carried out by Eclair, sound restored by L.E Diapason in partnership with Eclair. A screening organized to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the screening of the film opening the Festival de Cannes in 1988. The film will be screened at the Cinéma de la Plage (Movies on the Beach).

Driving Miss Daisy

by Bruce Beresford (1989, 1h40, United States of America)

Presented by Pathé. 4K restoration made from 35mm original image and sound negatives. Restoration carried out by Pathé L’image Retrouvée laboratory (Paris/Bologne) with the collaboration of director Bruce Beresford.

Cyrano de Bergerac

by Jean-Paul Rappeneau (1990, 2h15, France)

Presented by Lagardère Studios Distribution. Scan from the original negative and 4K restoration carried out by L’Image Retrouvée for Lagardère Studios Distribution with the support of the CNC, the Cinémathèque française, the Fonds Culturel Franco-Américain, Arte France–Unité Cinéma, Pathé et Mr. Francis Kurkdjian. French distribution in theaters: Carlotta Films (in progress). Jean-Paul Rappeneau in attendance.

Hyenas

by Djibril Diop Mambety (1992, 1h50, Senegal, France, Switzerland)

Lamb

by Paulin Soumanou Vieyra (1963, 18 min, Senegal) Presented by La Cinémathèque de l’Institut français, Orange and PSV Films. Digital restoration made from 2K scan of the 35mm negatives. Restoration carried out by Eclair.

El Massir (Destiny)

by Youssef Chahine (1997, 2h15, Egypt, France)

A preview of the full retrospective which will take place at the Cinémathèque française in October 2018, the film will be presented by Orange Studio and MISR International films with the support of the CNC, fostered by the Cinémathèque française. 4K restauration at Éclair Ymagis laboratory by Orange Studio, MISR International Films and the Cinémathèque française with the support of the CNC. The film will be screened at the Cinéma de la Plage (Movies on the Beach).

CANNES FILM FESTIVAL 71st EDITION | 8 -19 MAY 2018

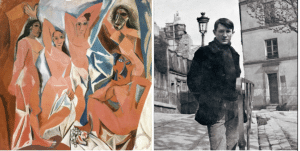

The Young Picasso

The Young Picasso

Writer/Dir: Lars von Trier | Cast: Uma Thurman, Matt Dillon, Riley Keough | Thriller | Bruno Ganz | 155′

Writer/Dir: Lars von Trier | Cast: Uma Thurman, Matt Dillon, Riley Keough | Thriller | Bruno Ganz | 155′ Dir: Rohena Gera | Drama | India | 97′

Dir: Rohena Gera | Drama | India | 97′ This year’s Cannes Classic sidebar has one or two priceless gems glittering in its antique crown. Apart from well-known legends: Ozu’s Tokyo Story, Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Wilder’s Apartment, Varda’s One Sings, The Other Doesn’t and Bondarchuks’ War and Peace, there are some worthwhile lesser known features not be missed.

This year’s Cannes Classic sidebar has one or two priceless gems glittering in its antique crown. Apart from well-known legends: Ozu’s Tokyo Story, Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Wilder’s Apartment, Varda’s One Sings, The Other Doesn’t and Bondarchuks’ War and Peace, there are some worthwhile lesser known features not be missed. Jacques Rivette is famous for his playful features such as Céline and Juliette go Boating, but his one and only excursion into mainstream, La Religieuse (1966), based on a Diderot novel, is full of anarchic fun. Suzanne Simonin (Anna Karina), is incarcerated in a cloister against her will, and soon falls foul of not one, but three Mother-Superiors: they treat her sadistically, tenderly, or as an object for plain lesbian lust – but Suzanne stays pure. This anti-clerical romp was very popular at the box office, and served as a liberating force for Karina who finally got a divorce from JL Godard after having acted in their final collaboration, Made in USA, in the same year.

Jacques Rivette is famous for his playful features such as Céline and Juliette go Boating, but his one and only excursion into mainstream, La Religieuse (1966), based on a Diderot novel, is full of anarchic fun. Suzanne Simonin (Anna Karina), is incarcerated in a cloister against her will, and soon falls foul of not one, but three Mother-Superiors: they treat her sadistically, tenderly, or as an object for plain lesbian lust – but Suzanne stays pure. This anti-clerical romp was very popular at the box office, and served as a liberating force for Karina who finally got a divorce from JL Godard after having acted in their final collaboration, Made in USA, in the same year. Hyenas (1992), directed by Senegalese filmmaker Djibri Diop Mambety (1945-1998), is a re-telling of the Durrenmatt play ‘Der Besuch der alten Dame’ (Visit of an old Lady). Set in an impoverished African village, the old lady in question is very rich – but she has not forgotten how her lover (now the Mayor) had treated her when she was pregnant with his child. She asks the townsfolk a simple question: do they want to participate in her wealth and punish the guilty man, or would they prefer clean hands and poverty. Colourful and very passionate, this adaption of a Swiss play works very well in its African setting.

Hyenas (1992), directed by Senegalese filmmaker Djibri Diop Mambety (1945-1998), is a re-telling of the Durrenmatt play ‘Der Besuch der alten Dame’ (Visit of an old Lady). Set in an impoverished African village, the old lady in question is very rich – but she has not forgotten how her lover (now the Mayor) had treated her when she was pregnant with his child. She asks the townsfolk a simple question: do they want to participate in her wealth and punish the guilty man, or would they prefer clean hands and poverty. Colourful and very passionate, this adaption of a Swiss play works very well in its African setting. Tôkyô monogatari (Tokyo Story / Voyage à Tokyo) by Yasujiro Ozu (1953, 2h15, Japan)

Tôkyô monogatari (Tokyo Story / Voyage à Tokyo) by Yasujiro Ozu (1953, 2h15, Japan) Vertigo by Alfred Hitchcock (1958, 2h08, United States of America)

Vertigo by Alfred Hitchcock (1958, 2h08, United States of America) Četri balti krekli (Four White Shirts)

Četri balti krekli (Four White Shirts)  João a faca e o rio (João and the Knife)

João a faca e o rio (João and the Knife) L’une chante, l’autre pas (One Sings the Other Doesn’t)

L’une chante, l’autre pas (One Sings the Other Doesn’t) Five and the Skin (Cinq et la peau)

Five and the Skin (Cinq et la peau)

Festival bigwig Thierry Frémaux warned us to expect shocks and surprises from this year’s festival line-up, distilled down from over 1900 features to an intriguing list of 18 – and there will be a few more additions before May 8th. The main question is “where are the stars?” or better still “Where is Isabelle Huppert” doyenne of the Croisette – up to now. The answer seems to be that they are on the jury –

Festival bigwig Thierry Frémaux warned us to expect shocks and surprises from this year’s festival line-up, distilled down from over 1900 features to an intriguing list of 18 – and there will be a few more additions before May 8th. The main question is “where are the stars?” or better still “Where is Isabelle Huppert” doyenne of the Croisette – up to now. The answer seems to be that they are on the jury –