In his latest feature Camille Claudel 1915, French auteur Bruno Dumont has remained faithful to his somewhat sincere, morbid take on humanity. In this instance we’re delving into the life of Camille Claudel – portrayed by Juliette Binoche – in her later years, when confined to a mental institution following the nervous breakdown that came as a result of her affair with Auguste Rodin. Dumont discusses his influences, how cautious he had to be when handling such a subject matter, the prevalence of patriarchal injustice in the film, and what attracts him to creating such unforgiving, often bleak feature films.

In his latest feature Camille Claudel 1915, French auteur Bruno Dumont has remained faithful to his somewhat sincere, morbid take on humanity. In this instance we’re delving into the life of Camille Claudel – portrayed by Juliette Binoche – in her later years, when confined to a mental institution following the nervous breakdown that came as a result of her affair with Auguste Rodin. Dumont discusses his influences, how cautious he had to be when handling such a subject matter, the prevalence of patriarchal injustice in the film, and what attracts him to creating such unforgiving, often bleak feature films.

Was the story of Camille Claudel one you knew much about prior to getting involved in this project?

It’s actually quite a well known story in France, she was a famous artist with this tragic destiny, ending up in a mental hospital. So yes, I knew about it before.

This isn’t the first film about Camille Claudel, with the 1980s take, starring Gérard Depardieu. Did you use that at all to inspire you – specifically in relation to Camille’s history with Rodin?

Yes, and because that film had been made, I didn’t need to cover that again, that aspect had been made into a film already. So I decided the next part of the story, which is far more obscure. Also, that moment in Camille’s life suits Juliette much better given her age.

Was delving in to a more obscure time in Camille’s life, allow you more artistic licence?

Yes, exactly. It’s more interesting because it’s more obscure and to study the psychiatry of an artist is very interesting to me.

With close-up shots of Juliette’s face, it reminded me of The Passion of Joan of Arc – was that an influence on this title?

Yes, and there is a relationship between the two women, because in a way they both burn. They’re both prisoners.

Another potential influence I could see is One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – especially in how our protagonist seemed to think that, in her mind, she was perhaps above everybody else there, and yet was unhinged herself.

Yeah, well the Claudel family are quite odd and very sure of their own genius. They have this superiority and are fully aware of their own genius. It makes them quite annoying, but that’s how they are. But yes, she was unhinged, it’s not a question of whether she is mad or not, it’s the length of time that she spent in there which is terrible. The problem is her brother’s influence in keeping her imprisoned. You have the scene with the doctor saying she’s much better and that she’s calmer and that she can be taken out. But the brother doesn’t. That’s the tension.

When treading on territory such as this, studying mental illness – how cautious do you have to be in order to remain sensitive to the subject matter?

I couldn’t imagine making actors play mad, so I had to be truthful by showing people who are genuinely mentally ill. So I was forced into that decision. Above all, Camille Claudel is writing about how hard it is to live with these women in her letters. So the whole mission of the film was to have this environment like that, with real patients. So I managed to find a psychiatrist who understood the therapeutic value of them being in the film, but you do need somebody to give you authorisation, so I had medical authorisation to do a casting in the hospital. Some people didn’t want to be in it, and some parents didn’t want their children to be in, so I just took people who did want to be in it.

In regards to Camille’s interaction with some of the other patients, we see quite a ruthless, callous side to her. Was it important for you to portray her flaws, to help us understand the character even more?

Yes, she was a hard, tough woman. She has this superiority about her, and she would treat everybody there like a lesser being – including her brother, who she calls ‘Little Paul’. She is pretty arrogant.

Was it ever a challenge to maintain that level of empathy, and yet show her for all of her imperfections?

I wasn’t judging her, I was taking as much as I could from the letters, which is as close as I could get to who the character was, and her relationships with other people. So I wasn’t trying to impose my own judgement on a historic character, you know, they are who they are. It’s the same for Paul, it’s easy to make him unlikeable – but I like him [laughs]. But he’s not a hero. He was a great writer, but he was also a coward. Like a lot of people. We’re all like that in some ways, and that’s the interesting part.

The film is very difficult to watch at times, and can be bleak and unforgiving. Do you get gratification from provoking such an emotional response from the viewer?

The film is difficult to watch because it’s difficult to look at mental illness. The film also takes you on a journey of love, by the end you love these women. In the end you find light. Camille is smiling by the end. In this journey, there is something that comes out that is a positive, in a way. The audience member, when they come out, can be happy, somehow. It’s a difficult journey, but can be a happy one.

This is not the first film of yours to tackle such severe themes – what attracts you to explore the darker, more dramatic side of life as a filmmaker?

In human beings there is lightness, darkness, happiness… I’m just occupied by the heavier side. You have to treat the serious side seriously, and the lighter side lightly. When you read Shakespeare, it’s not necessarily all funny, but in Shakespeare it is beautifully written, and in tragedy there is beauty. There is beauty in tragedy.

Back to Camille Claudel – how prevalent is the theme of patriarchal injustice?

Absolutely vital. It’s absolutely about that – at the beginning on the 20th century when women hadn’t been emancipated. She was ahead of her time, she was the light at the beginning of this century, but it was absolutely torturous, and she was rejected by all the people around her, even her family. It was very torturous. Especially Rodin, who abandoned her. For Rodin, she was a rival that really pissed him off, so she’s emblematic of women’s liberation. Poor Claudel is a kind of masochist, but also representative of his epoch.

At the heart of this tale, is an artist being denied her creativity. As an artist yourself, were you able to relate to the character and put yourself in her shoes, and wonder how you would react in this situation?

Yes, I was filming somebody who is forbidden life, forbidden creativity, forbidden freedom, and yes it’s touching. You touch a contemporary issue of alienation as well.

In regards to the look of the film, it’s a very beautiful aesthetic, creating a very serene atmosphere. Did you enjoying playing on the way that contradicts the inner turmoil?

It’s only through cinema that you can have, through these grimacing faces, the ability to show the beauty behind them. So the directing of the film has to be dignified, in order to show the women’s dignity as well.

In his latest feature Camille Claudel 1915, French auteur Bruno Dumont has remained faithful to his somewhat sincere, morbid take on humanity. In this instance we’re delving into the life of Camille Claudel – portrayed by Juliette Binoche – in her later years, when confined to a mental institution following the nervous breakdown that came as a result of her affair with Auguste Rodin. Dumont discusses his influences, how cautious he had to be when handling such a subject matter, the prevalence of patriarchal injustice in the film, and what attracts him to creating such unforgiving, often bleak feature films.

Was the story of Camille Claudel one you knew much about prior to getting involved in this project?

It’s actually quite a well known story in France, she was a famous artist with this tragic destiny, ending up in a mental hospital. So yes, I knew about it before.

This isn’t the first film about Camille Claudel, with the 1980s take, starring Gérard Depardieu. Did you use that at all to inspire you – specifically in relation to Camille’s history with Rodin?

Yes, and because that film had been made, I didn’t need to cover that again, that aspect had been made into a film already. So I decided the next part of the story, which is far more obscure. Also, that moment in Camille’s life suits Juliette much better given her age.

Was delving in to a more obscure time in Camille’s life, allow you more artistic licence?

Yes, exactly. It’s more interesting because it’s more obscure and to study the psychiatry of an artist is very interesting to me.

With close-up shots of Juliette’s face, it reminded me of The Passion of Joan of Arc – was that an influence on this title?

Yes, and there is a relationship between the two women, because in a way they both burn. They’re both prisoners.

Another potential influence I could see is One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – especially in how our protagonist seemed to think that, in her mind, she was perhaps above everybody else there, and yet was unhinged herself.

Yeah, well the Claudel family are quite odd and very sure of their own genius. They have this superiority and are fully aware of their own genius. It makes them quite annoying, but that’s how they are. But yes, she was unhinged, it’s not a question of whether she is mad or not, it’s the length of time that she spent in there which is terrible. The problem is her brother’s influence in keeping her imprisoned. You have the scene with the doctor saying she’s much better and that she’s calmer and that she can be taken out. But the brother doesn’t. That’s the tension.

When treading on territory such as this, studying mental illness – how cautious do you have to be in order to remain sensitive to the subject matter?

I couldn’t imagine making actors play mad, so I had to be truthful by showing people who are genuinely mentally ill. So I was forced into that decision. Above all, Camille Claudel is writing about how hard it is to live with these women in her letters. So the whole mission of the film was to have this environment like that, with real patients. So I managed to find a psychiatrist who understood the therapeutic value of them being in the film, but you do need somebody to give you authorisation, so I had medical authorisation to do a casting in the hospital. Some people didn’t want to be in it, and some parents didn’t want their children to be in, so I just took people who did want to be in it.

In regards to Camille’s interaction with some of the other patients, we see quite a ruthless, callous side to her. Was it important for you to portray her flaws, to help us understand the character even more?

Yes, she was a hard, tough woman. She has this superiority about her, and she would treat everybody there like a lesser being – including her brother, who she calls ‘Little Paul’. She is pretty arrogant.

Was it ever a challenge to maintain that level of empathy, and yet show her for all of her imperfections?

I wasn’t judging her, I was taking as much as I could from the letters, which is as close as I could get to who the character was, and her relationships with other people. So I wasn’t trying to impose my own judgement on a historic character, you know, they are who they are. It’s the same for Paul, it’s easy to make him unlikeable – but I like him [laughs]. But he’s not a hero. He was a great writer, but he was also a coward. Like a lot of people. We’re all like that in some ways, and that’s the interesting part.

The film is very difficult to watch at times, and can be bleak and unforgiving. Do you get gratification from provoking such an emotional response from the viewer?

The film is difficult to watch because it’s difficult to look at mental illness. The film also takes you on a journey of love, by the end you love these women. In the end you find light. Camille is smiling by the end. In this journey, there is something that comes out that is a positive, in a way. The audience member, when they come out, can be happy, somehow. It’s a difficult journey, but can be a happy one.

This is not the first film of yours to tackle such severe themes – what attracts you to explore the darker, more dramatic side of life as a filmmaker?

In human beings there is lightness, darkness, happiness… I’m just occupied by the heavier side. You have to treat the serious side seriously, and the lighter side lightly. When you read Shakespeare, it’s not necessarily all funny, but in Shakespeare it is beautifully written, and in tragedy there is beauty. There is beauty in tragedy.

Back to Camille Claudel – how prevalent is the theme of patriarchal injustice?

Absolutely vital. It’s absolutely about that – at the beginning on the 20th century when women hadn’t been emancipated. She was ahead of her time, she was the light at the beginning of this century, but it was absolutely torturous, and she was rejected by all the people around her, even her family. It was very torturous. Especially Rodin, who abandoned her. For Rodin, she was a rival that really pissed him off, so she’s emblematic of women’s liberation. Poor Claudel is a kind of masochist, but also representative of his epoch.

At the heart of this tale, is an artist being denied her creativity. As an artist yourself, were you able to relate to the character and put yourself in her shoes, and wonder how you would react in this situation?

Yes, I was filming somebody who is forbidden life, forbidden creativity, forbidden freedom, and yes it’s touching. You touch a contemporary issue of alienation as well.

In regards to the look of the film, it’s a very beautiful aesthetic, creating a very serene atmosphere. Did you enjoying playing on the way that contradicts the inner turmoil?

It’s only through cinema that you can have, through these grimacing faces, the ability to show the beauty behind them. So the directing of the film has to be dignified, in order to show the women’s dignity as well. STEFAN PAPE

[youtube id=”Q8mhgcMU-kI” width=”600″ height=”350″]

CAMILLE CLAUDEL 1915 IS NOW ON DVD- BLU RAY

Dirty weekends don’t come any dirtier than the one in this ferocious indie revenge thriller that has ravishing locations, a twisty storyline, and a female lead who is not just a pretty face.

Dirty weekends don’t come any dirtier than the one in this ferocious indie revenge thriller that has ravishing locations, a twisty storyline, and a female lead who is not just a pretty face. Le Corbeau (1942)

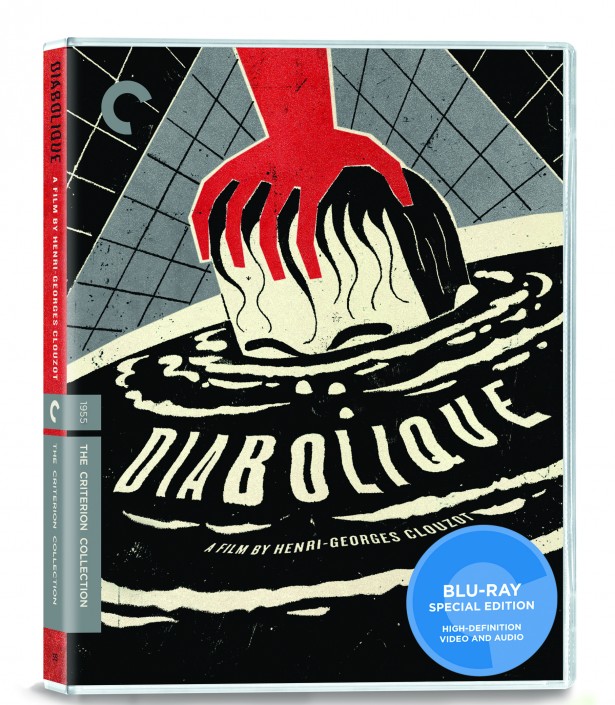

Le Corbeau (1942) Upon its release in 1943, Le Corbeau was condemned by the political left and right and the church, and Clouzot was banned from filmmaking for two years.

Upon its release in 1943, Le Corbeau was condemned by the political left and right and the church, and Clouzot was banned from filmmaking for two years. Woman in Chains (1968)

Woman in Chains (1968) Karina went on to star in seven of his films, the first was Le Petit Soldat that same year. She won Best Actress at the Berlin Film Festival in 1961 for Une Femme est une Femme. While marriage to Godard was stormy to say the least – he neglected her emotionally – “he was the sort of man who would go for a packet of cigarettes and return three weeks later” – their artistic relationship blossomed with a string of New Wave hits: Vivre sa Vie (1962); Bande a Part (1964); Pierrot Le Fou (1965); Alphaville (1965) and Made in USA (1966). When Godard cast her in his episode ‘Anticipation’ for The Oldest Profession (1966), they were already divorced and not on speaking terms. But Karina stayed loyal to Godard and a few years ago at the BFI she talked about him in glowing terms.

Karina went on to star in seven of his films, the first was Le Petit Soldat that same year. She won Best Actress at the Berlin Film Festival in 1961 for Une Femme est une Femme. While marriage to Godard was stormy to say the least – he neglected her emotionally – “he was the sort of man who would go for a packet of cigarettes and return three weeks later” – their artistic relationship blossomed with a string of New Wave hits: Vivre sa Vie (1962); Bande a Part (1964); Pierrot Le Fou (1965); Alphaville (1965) and Made in USA (1966). When Godard cast her in his episode ‘Anticipation’ for The Oldest Profession (1966), they were already divorced and not on speaking terms. But Karina stayed loyal to Godard and a few years ago at the BFI she talked about him in glowing terms.

Dir: Alain Resnais; Cast: Sabine Azéma, Pierre Arditi, André Dussollier, Fanny Ardant; France 1986, 112 min.

Dir: Alain Resnais; Cast: Sabine Azéma, Pierre Arditi, André Dussollier, Fanny Ardant; France 1986, 112 min.

But Julien Duvivier’s 1956 thriller DEADLIER THAN THE MALE (Voici les temps des Assassins) somehow manages to outdo them all when it comes to violent women in film Noir: Catherine (Delorme) is the daughter of the drug depending Gabrielle (Bogaert), and tries to escape from the milieu by marrying the restaurant owner Andre Chatelin (Gabin), who has divorced her mother. Telling him that Gabrielle is dead, the scheming Catherine succeeds in marrying the much older man, who soon learns that his wife is lying about her mother. He more or less imprisons her with her mother Antoinette (Bert), also a restaurant owner, who kills her chicken with a whip – which she also uses on Catherine. The frightened woman asks Andre’s friend, the student Gerard (Blain), to kill her husband, but when he refuses, she kills him. Her end – by the fangs of a particular vicious animal – is particularly gruesome. Again, the images of Armand Thirad are undeserving of this blatant ideology.

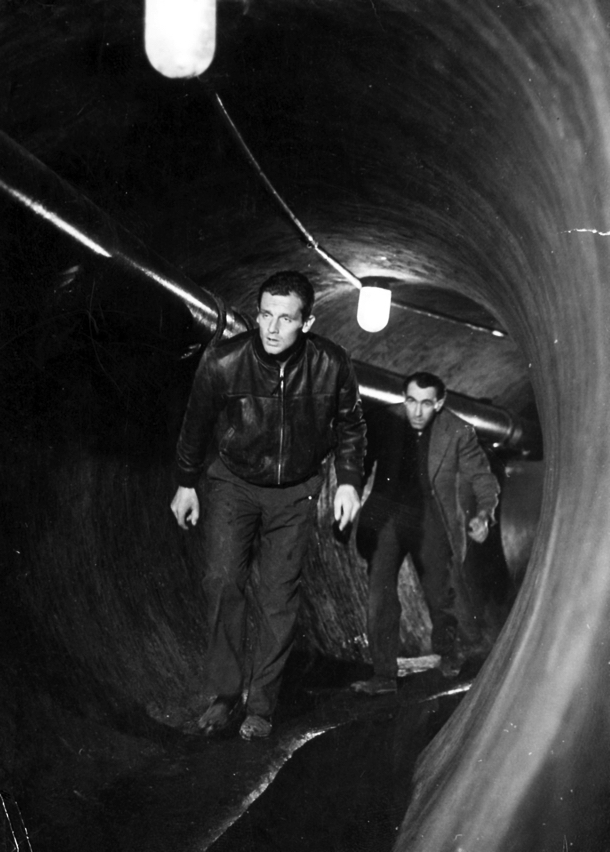

But Julien Duvivier’s 1956 thriller DEADLIER THAN THE MALE (Voici les temps des Assassins) somehow manages to outdo them all when it comes to violent women in film Noir: Catherine (Delorme) is the daughter of the drug depending Gabrielle (Bogaert), and tries to escape from the milieu by marrying the restaurant owner Andre Chatelin (Gabin), who has divorced her mother. Telling him that Gabrielle is dead, the scheming Catherine succeeds in marrying the much older man, who soon learns that his wife is lying about her mother. He more or less imprisons her with her mother Antoinette (Bert), also a restaurant owner, who kills her chicken with a whip – which she also uses on Catherine. The frightened woman asks Andre’s friend, the student Gerard (Blain), to kill her husband, but when he refuses, she kills him. Her end – by the fangs of a particular vicious animal – is particularly gruesome. Again, the images of Armand Thirad are undeserving of this blatant ideology. The notorious Pépé LE MOKO (Jean Gabin, in a truly iconic performance) plunges into the gangster underworld as a wanted man: women long for him, rivals hope to destroy him, and the law is breathing down his neck at every turn. On the lam in the labyrinthine Casbah of Algiers, Pépé is safe from the clutches of the police–until a Parisian playgirl compels him to risk his life and leave its confines once and for all. One of the most influential films of the 20th century and a landmark of French poetic realism, Julien Duvivier’s Pépé le moko is presented here in its full-length version. AVAILABLE FROM CRITERION COLLECTION | Amazon Prime

The notorious Pépé LE MOKO (Jean Gabin, in a truly iconic performance) plunges into the gangster underworld as a wanted man: women long for him, rivals hope to destroy him, and the law is breathing down his neck at every turn. On the lam in the labyrinthine Casbah of Algiers, Pépé is safe from the clutches of the police–until a Parisian playgirl compels him to risk his life and leave its confines once and for all. One of the most influential films of the 20th century and a landmark of French poetic realism, Julien Duvivier’s Pépé le moko is presented here in its full-length version. AVAILABLE FROM CRITERION COLLECTION | Amazon Prime Dir: Maurice Tourneur | Writer: Jean-Paul Le Chanois | Cast: Pierre Frenay, Josseline Gaël | Fantasy Horror | France 78′

Dir: Maurice Tourneur | Writer: Jean-Paul Le Chanois | Cast: Pierre Frenay, Josseline Gaël | Fantasy Horror | France 78′ WINTER’S CHILD (L’ENFANT DE L’HIVER) (1989) ****

WINTER’S CHILD (L’ENFANT DE L’HIVER) (1989) **** Dir.: Alain Resnais; Cast: Delphine Seyrig, Giorgio Albertazzi, Sacha Pitoeff; France/Italy 1961, 94 min

Dir.: Alain Resnais; Cast: Delphine Seyrig, Giorgio Albertazzi, Sacha Pitoeff; France/Italy 1961, 94 min

Dir.: Jean Renoir; Cast: Rene Lefevre, Florelle, Jules Berry, Nadia Sibirskaia; France 1936, 80 min.

Dir.: Jean Renoir; Cast: Rene Lefevre, Florelle, Jules Berry, Nadia Sibirskaia; France 1936, 80 min. Vagabond

Vagabond

Artistic director Carlo Chatrian has unveiled his final line-up with an exciting eclectic selection of titles spanning mainstream and arthouse fare due to run at the picturesque Lake Maggiore setting from the 1st until 11th August 2018.

Artistic director Carlo Chatrian has unveiled his final line-up with an exciting eclectic selection of titles spanning mainstream and arthouse fare due to run at the picturesque Lake Maggiore setting from the 1st until 11th August 2018.

This year’s Cannes Classic sidebar has one or two priceless gems glittering in its antique crown. Apart from well-known legends: Ozu’s Tokyo Story, Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Wilder’s Apartment, Varda’s One Sings, The Other Doesn’t and Bondarchuks’ War and Peace, there are some worthwhile lesser known features not be missed.

This year’s Cannes Classic sidebar has one or two priceless gems glittering in its antique crown. Apart from well-known legends: Ozu’s Tokyo Story, Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Wilder’s Apartment, Varda’s One Sings, The Other Doesn’t and Bondarchuks’ War and Peace, there are some worthwhile lesser known features not be missed. Jacques Rivette is famous for his playful features such as Céline and Juliette go Boating, but his one and only excursion into mainstream, La Religieuse (1966), based on a Diderot novel, is full of anarchic fun. Suzanne Simonin (Anna Karina), is incarcerated in a cloister against her will, and soon falls foul of not one, but three Mother-Superiors: they treat her sadistically, tenderly, or as an object for plain lesbian lust – but Suzanne stays pure. This anti-clerical romp was very popular at the box office, and served as a liberating force for Karina who finally got a divorce from JL Godard after having acted in their final collaboration, Made in USA, in the same year.

Jacques Rivette is famous for his playful features such as Céline and Juliette go Boating, but his one and only excursion into mainstream, La Religieuse (1966), based on a Diderot novel, is full of anarchic fun. Suzanne Simonin (Anna Karina), is incarcerated in a cloister against her will, and soon falls foul of not one, but three Mother-Superiors: they treat her sadistically, tenderly, or as an object for plain lesbian lust – but Suzanne stays pure. This anti-clerical romp was very popular at the box office, and served as a liberating force for Karina who finally got a divorce from JL Godard after having acted in their final collaboration, Made in USA, in the same year. Hyenas (1992), directed by Senegalese filmmaker Djibri Diop Mambety (1945-1998), is a re-telling of the Durrenmatt play ‘Der Besuch der alten Dame’ (Visit of an old Lady). Set in an impoverished African village, the old lady in question is very rich – but she has not forgotten how her lover (now the Mayor) had treated her when she was pregnant with his child. She asks the townsfolk a simple question: do they want to participate in her wealth and punish the guilty man, or would they prefer clean hands and poverty. Colourful and very passionate, this adaption of a Swiss play works very well in its African setting.

Hyenas (1992), directed by Senegalese filmmaker Djibri Diop Mambety (1945-1998), is a re-telling of the Durrenmatt play ‘Der Besuch der alten Dame’ (Visit of an old Lady). Set in an impoverished African village, the old lady in question is very rich – but she has not forgotten how her lover (now the Mayor) had treated her when she was pregnant with his child. She asks the townsfolk a simple question: do they want to participate in her wealth and punish the guilty man, or would they prefer clean hands and poverty. Colourful and very passionate, this adaption of a Swiss play works very well in its African setting. Tôkyô monogatari (Tokyo Story / Voyage à Tokyo) by Yasujiro Ozu (1953, 2h15, Japan)

Tôkyô monogatari (Tokyo Story / Voyage à Tokyo) by Yasujiro Ozu (1953, 2h15, Japan) Vertigo by Alfred Hitchcock (1958, 2h08, United States of America)

Vertigo by Alfred Hitchcock (1958, 2h08, United States of America) Četri balti krekli (Four White Shirts)

Četri balti krekli (Four White Shirts)  João a faca e o rio (João and the Knife)

João a faca e o rio (João and the Knife) L’une chante, l’autre pas (One Sings the Other Doesn’t)

L’une chante, l’autre pas (One Sings the Other Doesn’t) Five and the Skin (Cinq et la peau)

Five and the Skin (Cinq et la peau) Festival bigwig Thierry Frémaux warned us to expect shocks and surprises from this year’s festival line-up, distilled down from over 1900 features to an intriguing list of 18 – and there will be a few more additions before May 8th. The main question is “where are the stars?” or better still “Where is Isabelle Huppert” doyenne of the Croisette – up to now. The answer seems to be that they are on the jury –

Festival bigwig Thierry Frémaux warned us to expect shocks and surprises from this year’s festival line-up, distilled down from over 1900 features to an intriguing list of 18 – and there will be a few more additions before May 8th. The main question is “where are the stars?” or better still “Where is Isabelle Huppert” doyenne of the Croisette – up to now. The answer seems to be that they are on the jury –

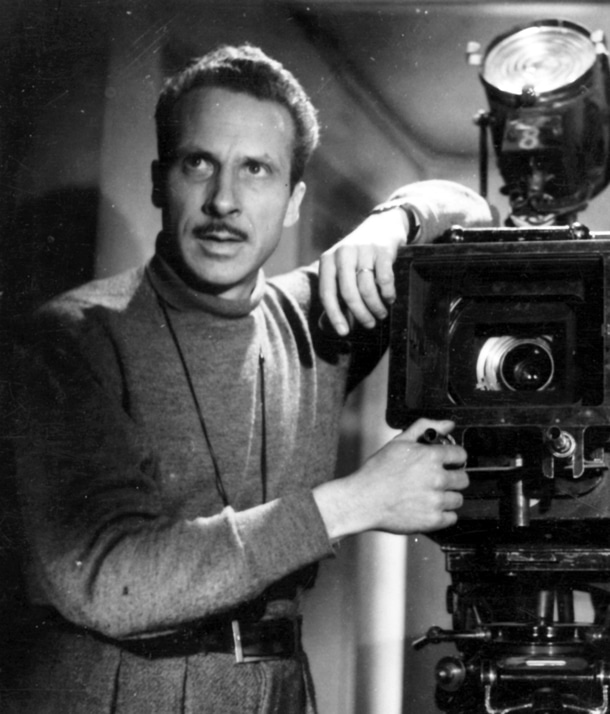

s Dee), a Canadian nurse, takes care of Jessica (Christine Gordon) on the West Indian island of St. Sebastian. Jessica is married to the sugar planter Paul Holland (Tom Conway). She falls in love with Paul’s half-brother Wesley (James Ellison). After a scene with her husband, she falls into a trauma, and after several attempts of ‘curing’ her, Mrs. Rand (Edith Barnett), Paul and Wesley’s mother confesses that she has cast a voodoo spell on Jessica for bringing the family into disrepute. Wesley finally kills Jessica, to set her free. Tourneur preferred Zombie to Cat People, and often cited it as his favourite film. Zombie is Tourneur’s purest film when it comes to cinematic poetry, combining sounds and images into a “power of suggestion”, enhanced by the film’s narrative, which is full of enigma and contradiction, eluding any attempt to interpret it in a linear way. Zombie “is a sustained exercise in uncompromising ambiguity. Perfecting the formula that Lewton and Tourneur had developed in Cat People, the film carries its predecessor’s elliptical, oblique narrative procedures to astonishing extremes. The dialogue is almost nothing but a commentary on past events, obsessively revisiting itself, finally giving up the struggle and surrendering to a mute acceptance of the inexplicable. We watch the slow, atmospheric, lovingly detailed scenes with delight and fascination, realising at the end, that we have seen nothing but the traces of a conflict decided in advance.” (Chris Fujiwara).

s Dee), a Canadian nurse, takes care of Jessica (Christine Gordon) on the West Indian island of St. Sebastian. Jessica is married to the sugar planter Paul Holland (Tom Conway). She falls in love with Paul’s half-brother Wesley (James Ellison). After a scene with her husband, she falls into a trauma, and after several attempts of ‘curing’ her, Mrs. Rand (Edith Barnett), Paul and Wesley’s mother confesses that she has cast a voodoo spell on Jessica for bringing the family into disrepute. Wesley finally kills Jessica, to set her free. Tourneur preferred Zombie to Cat People, and often cited it as his favourite film. Zombie is Tourneur’s purest film when it comes to cinematic poetry, combining sounds and images into a “power of suggestion”, enhanced by the film’s narrative, which is full of enigma and contradiction, eluding any attempt to interpret it in a linear way. Zombie “is a sustained exercise in uncompromising ambiguity. Perfecting the formula that Lewton and Tourneur had developed in Cat People, the film carries its predecessor’s elliptical, oblique narrative procedures to astonishing extremes. The dialogue is almost nothing but a commentary on past events, obsessively revisiting itself, finally giving up the struggle and surrendering to a mute acceptance of the inexplicable. We watch the slow, atmospheric, lovingly detailed scenes with delight and fascination, realising at the end, that we have seen nothing but the traces of a conflict decided in advance.” (Chris Fujiwara).

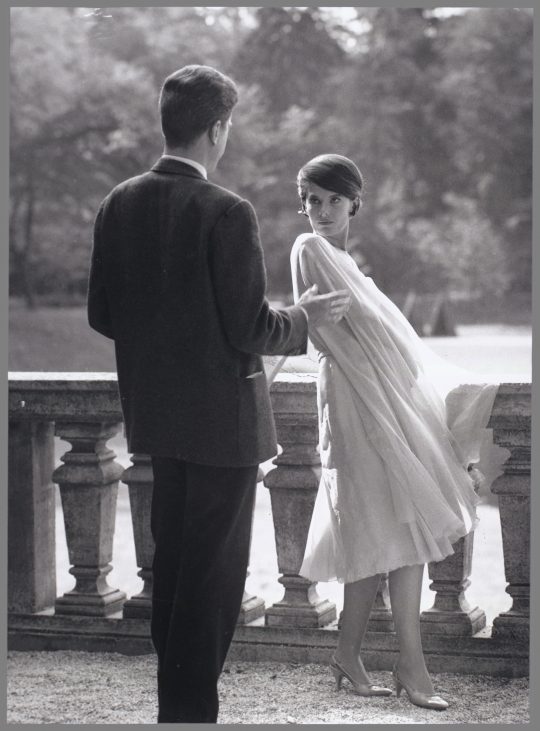

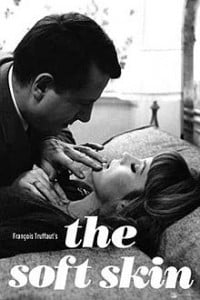

Truffaut’s La Peau Douce is known, in translation, as Soft Skin, as it best conveys the film’s vulnerability of character and minimal eroticism. It’s a superb, understated study of adultery that descends into a crime passionel.

Truffaut’s La Peau Douce is known, in translation, as Soft Skin, as it best conveys the film’s vulnerability of character and minimal eroticism. It’s a superb, understated study of adultery that descends into a crime passionel.