Dresden 1918, Robert Siodmak left his upper-middle class, orthodox Jewish home in this epicentre of European modern art, to join a theatre touring company. He was 18, and this was the first of many radical changes that would see him becoming a pioneer of film noir, and directing 56 feature films fraught with (anti)heroes who are morose, malevolent, violent and generally downbeat (spoilers).

Dresden 1918, Robert Siodmak left his upper-middle class, orthodox Jewish home in this epicentre of European modern art, to join a theatre touring company. He was 18, and this was the first of many radical changes that would see him becoming a pioneer of film noir, and directing 56 feature films fraught with (anti)heroes who are morose, malevolent, violent and generally downbeat (spoilers).

Robert Siodmak began his film career in 1925, translating inter-titles. Later he learnt the editing business with Harry Piel. In 1927/28 he worked under Kurt (Curtis) Bernhardt (Das letzte Fort) and Alfred Lind. But MENSCHEN AM SONNTAG (1929/30) (left) would transform his professional life forever. Together with Edgar G. Ulmer, he would direct a semi-documentary, social realist portrait that pictured ordinary Berliners, far away from the expensive “Illusionsfilme” (escapist films) of the UFA. The idea was the brainchild of Robert’s younger brother Curt (born in Kracow), who would become a screen-writer and director of Horror/SF films, and follow his brother and Ulmer to Hollywood – along with the rest of the team: Billy Wilder, Eugen Schüfftan, Fred Zinnemann and Rochus Gliese (later art director for Murnau’s Sunrise). Robert Siodmak, Ulmer and Giese would also be part of the “Remigrants”, film makers, who would return to Germany after 1945.

MENSCHEN AM SONNTAG was filmed on a succession of Sundays in 1929. Subtitled “a film without actors” – which is misleading, since the actors – non-professionals – co-wrote and co-produced the film, had already returned to their day jobs when the film was premiered in 1930. The five main protagonists spend a weekend near a lake in a Berlin suburb: Wolfgang (a wine seller) and Christl (a mannequin) meet for the first time at the Bahnhof Zoo by accident on Saturday morning, Christl had been stood up. On the same evening, Erwin (a taxi driver) and his girl friend Annie have a violent quarrel, tearing up each other’s photos. As a result, Erwin and his friend Wolfgang travel with Christl on the following Sunday to the Nicolas Lake. And here on the ‘beach’ Wolfgang meets Brigitte (a vinyl record sales assistant), the four spend the day together; intercut with images of the forlorn “stay-at-home” Annie. The final scene returns the quartet to the heart of the metropolis: four million waiting for another Sunday. MENSCHEN AM SONNTAG is a chronicle; a document shot against the narrative UFA style of the day. There is no story, just interaction. Even in the complex narratives of his films Noir, Siodmak would always be the bystander, the person who observes much more than directs.

MENSCHEN AM SONNTAG was filmed on a succession of Sundays in 1929. Subtitled “a film without actors” – which is misleading, since the actors – non-professionals – co-wrote and co-produced the film, had already returned to their day jobs when the film was premiered in 1930. The five main protagonists spend a weekend near a lake in a Berlin suburb: Wolfgang (a wine seller) and Christl (a mannequin) meet for the first time at the Bahnhof Zoo by accident on Saturday morning, Christl had been stood up. On the same evening, Erwin (a taxi driver) and his girl friend Annie have a violent quarrel, tearing up each other’s photos. As a result, Erwin and his friend Wolfgang travel with Christl on the following Sunday to the Nicolas Lake. And here on the ‘beach’ Wolfgang meets Brigitte (a vinyl record sales assistant), the four spend the day together; intercut with images of the forlorn “stay-at-home” Annie. The final scene returns the quartet to the heart of the metropolis: four million waiting for another Sunday. MENSCHEN AM SONNTAG is a chronicle; a document shot against the narrative UFA style of the day. There is no story, just interaction. Even in the complex narratives of his films Noir, Siodmak would always be the bystander, the person who observes much more than directs.

INQUEST (VORUNTERSUCHUNG), Robert Siodmak’s third feature film as a director, produced in 1931, is his first ‘Kriminalfilm” (thriller). The student Fritz Bernt (Gustaf Fröhlich), has a three year-long affair with the prostitute Erna – he also receives money from her. After falling in love with his friend Walter’s sister, Fritz wants to leave Erna. Out of cowardice, he sends Walter to her flat to break the news. But Walter sleeps with Erna’s flatmate and goes for a drink afterwards. When Erna’s body is found the next morning, Fritz is the main suspect. In charge of the inquest is Dr. Bienert (Albert Bassermann), who happens to be Walter’s father. The denouement is a surprise. In many ways, INQUEST is a “Strassenfilm”, Kracauer’s definition of films where the middle-class protagonist is in love with a sexy prostitute, but goes home to roost, marrying a bourgeois girl of his own class. Some of the main scenes of the film are shot in the staircase of the house where Erna lives, the shadowy lighting clearly foreshadowing Siodmak’s Noir period. Sexuality is the enemy of bourgeois society here, and Bassermann’s Dr. Bienert is a blustering patriarch, who would sacrifice anyone to save his son.

INQUEST (VORUNTERSUCHUNG), Robert Siodmak’s third feature film as a director, produced in 1931, is his first ‘Kriminalfilm” (thriller). The student Fritz Bernt (Gustaf Fröhlich), has a three year-long affair with the prostitute Erna – he also receives money from her. After falling in love with his friend Walter’s sister, Fritz wants to leave Erna. Out of cowardice, he sends Walter to her flat to break the news. But Walter sleeps with Erna’s flatmate and goes for a drink afterwards. When Erna’s body is found the next morning, Fritz is the main suspect. In charge of the inquest is Dr. Bienert (Albert Bassermann), who happens to be Walter’s father. The denouement is a surprise. In many ways, INQUEST is a “Strassenfilm”, Kracauer’s definition of films where the middle-class protagonist is in love with a sexy prostitute, but goes home to roost, marrying a bourgeois girl of his own class. Some of the main scenes of the film are shot in the staircase of the house where Erna lives, the shadowy lighting clearly foreshadowing Siodmak’s Noir period. Sexuality is the enemy of bourgeois society here, and Bassermann’s Dr. Bienert is a blustering patriarch, who would sacrifice anyone to save his son.

THE BURNING SECRET (BRENNENDES GEHEIMNIS) is based on a novel by Stefan Zweig. Shot in 1932, it was to be Siodmak’s last German film for 23 years. In a Swiss Sanatorium, the twelve-year old Edgar (H.J. Schaufuss) is bored, and pleased to befriend Baron Von Haller (Willi Forst), a racing driver. But he does not know that Von Haller is using him to get close to his mother (Hilde Wagner). Soon Edgar gets suspicious, the two adults always want to be alone. He surprises them in flagrante and runs home to his father, although he does not give his secret away. When his mother arrives, he looks at her knowingly, but stays ‘mum’. Siodmak has sharpened the edges of this coming-of-age story, the novel concentrating more on romantic and psychological aspects. There is real violence between Edgar and Von Haller, and the lovemaking of the adulterous couple, which Edgar interrupts, is more vicious than affectionate. When the film was premiered in March 1933, Siodmak was already living in Paris, and Goebbels denounced the film as un-German, not surprisingly, since both the author of the novel and the director of the film were Jews living abroad in exile.

When Siodmak shot MOLLENARD (1937) in France, it would be the penultimate of his French-set features. (In 1938, he would finish “Ultimatum” for the fatally ill Robert Wiene; and in the same year he is credited with “artistic supervision” for Vendetta, directed by Georges Kelber). MOLLENARD (HATRED) is the nearest to a film Noir so far: it is a fight to the death between Captain Mollenard (Harry Baur) and his wife Mathide (Gabrielle Dorziat). Captain Mollenard is a gun runner in Shanghai, he is shown as a hero, a good friend to his crew. When he returns to Dunkirk and his wife and two children, illness renders him powerless to his vitriolic wife, who tries to turn the children against him. Mollenard attempts to use his strength to re-conquer his wife, but fails, unlike during his days in Shanghai. The son takes the side of his mother, the daughter tries to drown herself, but Mollenard saves her. In the end, his crew carries the dying man out of the house, he would end his life where he was most happy – at sea. MOLLENARD is a contrast between utopia and dystopia for the main protagonist: the sea, where he is free (to commit crimes), and the bourgeois home, where he is a prisoner of conventions. He is unable to survive in this which cold, emotionless prison. MOLLENARD is seen as his greatest film in France, a dramatic version of Noir.

When Siodmak shot MOLLENARD (1937) in France, it would be the penultimate of his French-set features. (In 1938, he would finish “Ultimatum” for the fatally ill Robert Wiene; and in the same year he is credited with “artistic supervision” for Vendetta, directed by Georges Kelber). MOLLENARD (HATRED) is the nearest to a film Noir so far: it is a fight to the death between Captain Mollenard (Harry Baur) and his wife Mathide (Gabrielle Dorziat). Captain Mollenard is a gun runner in Shanghai, he is shown as a hero, a good friend to his crew. When he returns to Dunkirk and his wife and two children, illness renders him powerless to his vitriolic wife, who tries to turn the children against him. Mollenard attempts to use his strength to re-conquer his wife, but fails, unlike during his days in Shanghai. The son takes the side of his mother, the daughter tries to drown herself, but Mollenard saves her. In the end, his crew carries the dying man out of the house, he would end his life where he was most happy – at sea. MOLLENARD is a contrast between utopia and dystopia for the main protagonist: the sea, where he is free (to commit crimes), and the bourgeois home, where he is a prisoner of conventions. He is unable to survive in this which cold, emotionless prison. MOLLENARD is seen as his greatest film in France, a dramatic version of Noir.

PIÈGES (1939) was Siodmak’s last French film before emigrating to the USA – and his greatest box-office success of this period. Whilst most of Siodmak’s French films featured fellow emigrés in front and behind the camera, PIÈGES only has the co-author, Ernst Neubach, as a fellow emigré– the DOP, Ted Pahle, was American, and the star, Maurice Chevalier, already an legend was very much a Frenchman: Siodmak had established himself. (A fact, which would count for nothing at the start of his US career.) PIÈGES is the story of a serial killer who murders eleven women in the music-hall world of Paris. The police, whose main suspect is the night-club-owner and womaniser Fleury (Chevalier), chooses Arienne (the debutant Marie Dea), to lure the murderer into the open. But Arienne falls in love with Fleury’s associate Brémontière, only to find out that he is the murderer. In the end the gutsy Arienne (Dea is a subtle antithesis to the French heroines of this period) has to risk her lift to save her husband Fleury’s. There are more than a few clues to the later “Phantom Lady” in PIÈGES. Eric von Stroheim is brilliant as a mad fashion czar who has lost his fortune and adoring women.

PIÈGES (1939) was Siodmak’s last French film before emigrating to the USA – and his greatest box-office success of this period. Whilst most of Siodmak’s French films featured fellow emigrés in front and behind the camera, PIÈGES only has the co-author, Ernst Neubach, as a fellow emigré– the DOP, Ted Pahle, was American, and the star, Maurice Chevalier, already an legend was very much a Frenchman: Siodmak had established himself. (A fact, which would count for nothing at the start of his US career.) PIÈGES is the story of a serial killer who murders eleven women in the music-hall world of Paris. The police, whose main suspect is the night-club-owner and womaniser Fleury (Chevalier), chooses Arienne (the debutant Marie Dea), to lure the murderer into the open. But Arienne falls in love with Fleury’s associate Brémontière, only to find out that he is the murderer. In the end the gutsy Arienne (Dea is a subtle antithesis to the French heroines of this period) has to risk her lift to save her husband Fleury’s. There are more than a few clues to the later “Phantom Lady” in PIÈGES. Eric von Stroheim is brilliant as a mad fashion czar who has lost his fortune and adoring women.

SON OF DRACULA (1943) was already Robert Siodmak’s seventh film in Hollywood, his first for Universal. Scripted by his brother Curt, SON OF DRACULA was a great risk for Robert, it was his first outing in the classical Horror genre, not to mention the great ‘Dracula tradition’ started by Ted Browning in 1931. The film is set in the bayous of Louisianna, where Katherine Caldwell has inherited the plantation “Dark Oaks” from her father, who died suddenly under mysterious circumstances. She gives a party, and entertains Count Alucard (Lon Chaney jr.) an acquaintance from her travels in central Europe. She discards her fiancée Frank and marries Alucard. Frank shoots the count, but the bullet passes through him, killing Katherine. In prison, Katherine visits him as a bat, turning into her human form (a first in film history), and asking Frank to kill Alucard, so they can live together forever as vampires. Frank grants her wish, but also burns her in her coffin. SON OF DRACULA is pure gothic horror, but suffered from Lon Chaney jr. being miscast in a role created by Bela Lugosi as his Alter Ego. Strongest are the scenes in the bayous, where the evil still lurks after the death of Katherine and Alucard: everything seems toxic, the spell of the vampire lives on.

COBRA WOMAN (1943) was Robert Siodmak’s first film in colour, shot in widescreen Technicolor. Its star, Maria Montez, an aristocrat from the Dominican Republic, whose real name was Maria Africa Garcia Vidal de Santo Silas, would later gain cult status after her early death at the age of 39 from a heart attack in her bathtub in Paris. Maria plays Tollea, who is whisked away just before her wedding to Ramu, to her birth island where her evil twin sister Naja (also played by Montez) holds sway. Ramu and his helper Kado follow her, but Tollea has decided to sacrifice her love for Ramu to become the new ruler of the island, so as to prevent an eruption of the volcano provoked by Naja’s sins. COBRA WOMAN is pure camp, Siodmak said “it was nonsense, but fun”.

COBRA WOMAN (1943) was Robert Siodmak’s first film in colour, shot in widescreen Technicolor. Its star, Maria Montez, an aristocrat from the Dominican Republic, whose real name was Maria Africa Garcia Vidal de Santo Silas, would later gain cult status after her early death at the age of 39 from a heart attack in her bathtub in Paris. Maria plays Tollea, who is whisked away just before her wedding to Ramu, to her birth island where her evil twin sister Naja (also played by Montez) holds sway. Ramu and his helper Kado follow her, but Tollea has decided to sacrifice her love for Ramu to become the new ruler of the island, so as to prevent an eruption of the volcano provoked by Naja’s sins. COBRA WOMAN is pure camp, Siodmak said “it was nonsense, but fun”.

In 1943 Siodmak was on a roll: he would make four film that year, and PHANTOM LADY (1943) was also the most important of his American period to date: the first of a quartet, which would form with The Spiral Staircase, The Killers and Criss Cross, the classic Noir films of their creator.

In 1943 Siodmak was on a roll: he would make four film that year, and PHANTOM LADY (1943) was also the most important of his American period to date: the first of a quartet, which would form with The Spiral Staircase, The Killers and Criss Cross, the classic Noir films of their creator.

PHANTOM LADY is based on a novel by Cornell Woolrich (William Irish), a prolific writer, whose novels and short stories were the basis for twenty films Noir of the classic period. They also provided the basis for Nouvelle Vague fare. Pivotal in Woolrich’s novels is the race against time. Scott Henderson, an engineer, is accused of murdering his wife. He proclaims his innocence, but is sentenced to death. His secretary Carol “Kansas” Richman (Ella Raines) is convinced he is not a murderer, and together with inspector Burges, she sets out to find the real culprit. Henderson’s alibi is a woman with a flamboyant hat, he meets in a bar, and spends the evening with, while his wife was murdered – but they promised not to reveal their identities. The mystery woman is illusive and when Carol tries to unravel her identity, the barman, who to denies having seen her at all, is run over by a car shortly after interviewed by Richman. Another witness, a drummer (Elisha Cook. Jr.), is also murdered, before Richman corners Franchot Tone, an artist, and Richman’s best friend as the murderer: he had an affair with Richman’s wife. German expressionism and Siodmak’s customary near documentary style dominate: New York is a bed of intrigue, where shadows lurk and footsteps signal danger. The majority of scenes could be watched without dialogue, particularly Cook’s drummer solo, which fits in well with the impressionist décor. With PHANTOM LADY, Robert Siodmak had found his (sub)genre.

CHRISTMAS HOLIDAY (1944), based on a novel by Somerset Maugham, has a most misleading title and is perhaps Siodmak’s most exotic film Noir. Lt. Mason, on Christmas leave, is delayed in New Orleans, where he meets the singer Jackie Lamont (Deanna Durham) who tells him her real name is Abigail Manette, and that her husband Robert (Gene Kelly) is in jail for murdering his bookie. In a long flashback, we see Robert’s mother trying to cover up her son’s crime. After Jackie leaves Mason, she is confronted in a roadhouse by Robert who has escaped from jail. Before he can shoot her, a policeman’s bullet kills him. Like “Phantom Lady”, CHRISTMAS HOLIDAY is photographed again by Woody Bredell, New Orleans is a tropical, outlandish setting and the film has much more the feel of a French film-noir than an American. Siodmak uses Wagner’s “Liebestod” to frame the love story of the doomed couple.

CHRISTMAS HOLIDAY (1944), based on a novel by Somerset Maugham, has a most misleading title and is perhaps Siodmak’s most exotic film Noir. Lt. Mason, on Christmas leave, is delayed in New Orleans, where he meets the singer Jackie Lamont (Deanna Durham) who tells him her real name is Abigail Manette, and that her husband Robert (Gene Kelly) is in jail for murdering his bookie. In a long flashback, we see Robert’s mother trying to cover up her son’s crime. After Jackie leaves Mason, she is confronted in a roadhouse by Robert who has escaped from jail. Before he can shoot her, a policeman’s bullet kills him. Like “Phantom Lady”, CHRISTMAS HOLIDAY is photographed again by Woody Bredell, New Orleans is a tropical, outlandish setting and the film has much more the feel of a French film-noir than an American. Siodmak uses Wagner’s “Liebestod” to frame the love story of the doomed couple.

THE SUSPECT (1944) is one of Siodmak’s less convincing Noirs. Philip Marshall (Charles Laughton), a sedentary middle-aged man, is driven out by his heartless wife Cora, and falls in love with the much younger Mary (Ella Raines). Philip becomes a different person, and thrives with his new love. But Cora finds out about the couple and threatens Philip with disclosure, which would have ruined him professionally. He kills first Cora, then his neighbour Gilbert Simmons, who blackmails him. Inspector Huxley has no proof against him, and Philip could start a new life with his young wife in Canada, but he decides to stay and give himself up, just as Huxley had predicted. Shot entirely in a studio, THE SUSPECT lacks suspense, and is only remarkable for Laughton’s brilliant performance.

THE STRANGE AFFAIR OF UNCLE HARRY (1945) features a semi-incestuous relationship between brother and sister: John “Harry” Quincy (George Sanders) lives a quiet life in New Hampshire with his sisters Lettie (Geraldine Fitzgerald) and Hester. When he meets the fashion designer Deborah Brown (Ella Raines), he falls in love with her. Lettie is jeaulous, and feigns a heart attack. Harry wants to murder her, but Hester drinks the poison intended for Lettie, who is convicted for Hester’s murder, but does not give away the real culprit, since she knows that her death will prevent Harry from marrying Deborah. To mollify The “MPAA code agency”, Siodmak found a new ending: Harry wakes up at, having only dreamt the events; producer Joan Harrison resigned from the project in protest. Lettie is a psychopath in the vein of the murderer in Phantom Lady and Olivia de Havilland’s murderous twin in The Dark Mirror. But there is more ambiguity to the narrative than is obvious at first sight: there is a vey clear resemblance between Lettie and Deborah – they might have been exchangeable for Harry. THE STRANGE AFFAIR OF UNCLE HARRY is one of the darkest Noirs, because all is played out on the background of a very respectable family, in small town America.

THE STRANGE AFFAIR OF UNCLE HARRY (1945) features a semi-incestuous relationship between brother and sister: John “Harry” Quincy (George Sanders) lives a quiet life in New Hampshire with his sisters Lettie (Geraldine Fitzgerald) and Hester. When he meets the fashion designer Deborah Brown (Ella Raines), he falls in love with her. Lettie is jeaulous, and feigns a heart attack. Harry wants to murder her, but Hester drinks the poison intended for Lettie, who is convicted for Hester’s murder, but does not give away the real culprit, since she knows that her death will prevent Harry from marrying Deborah. To mollify The “MPAA code agency”, Siodmak found a new ending: Harry wakes up at, having only dreamt the events; producer Joan Harrison resigned from the project in protest. Lettie is a psychopath in the vein of the murderer in Phantom Lady and Olivia de Havilland’s murderous twin in The Dark Mirror. But there is more ambiguity to the narrative than is obvious at first sight: there is a vey clear resemblance between Lettie and Deborah – they might have been exchangeable for Harry. THE STRANGE AFFAIR OF UNCLE HARRY is one of the darkest Noirs, because all is played out on the background of a very respectable family, in small town America.

THE SPIRAL STAIRCASE (1945) is Siodmak’s most famous Noir, a classic because of its old-dark-house setting and the woman-in-peril theme. In a small town in New England, handicapped women are being murdered. Helen (Dorothy McGuire) is watching a silent movie in town, where a lame woman is strangled. Helen then hurries home, to look after the family matriarch Mrs. Warren (Ethel Barrymore), who is bedridden. Since Helen is mute, she is in mortal danger: the killer lives in the house. When Helen finds the body of Blanche, who was engaged to Albert Warren (George Brent), after having left his half-brother Steve, Helen suspects Stephen and locks him in the cellar; then she tries to phone Dr. Parry, but she cannot communicate. Too late she finds out that Albert is the killer, who chases her up the spiral staircase, but his mother gets up and shoots him, causing Helen, who lost her voice after witnessing the traumatic death of her parents, to cry out loud. Very little of the background to the narrative has been mentioned: the theme being eugenics, a concept the late President Theodore Roosevelt was very keen on. Albert Warren has taken this concept a step further; he kills “weak and imperfect” humans because he believes his father would be proud of him. Like T. Roosevelt, Albert’s father was a big-game hunter. In his mother’s bedroom is a poster with a Teddy Roosevelt lookalike and the initials “TR” above an elephant’s tusk. Considering the Nazi Euthanasia programmes, this aspect of THE SPIRAL STAIRCASE has often been neglected by critics.

THE DARK MIRROR (1946) reflects Hollywood’s interest in Freud. Two identical sisters, Terry and Ruth Collins, both played by Olivia de Havilland, are suspected of murder, when one of the women’s suitors is found dead. Inspector Stevenson is fascinated by the two woman, but would not have solved the crime without the help of Dr. Elliot, a psychoanalyst. He finds out that whilst Ruth is a very adjusted and loving person, Terry is just her opposite: a ruthless psychopath, who fabricates clues, to make Ruth look like the murderess, whilst at the same time is planning to kill her sister, before Dr. Elliot is able to expose her. Siodmak deals with the “Doppelgänger” theme, which was explored as early as in the silent film era of expressionism, by using Freudian theory to explain the perversity of the “evil” sister: rejection, confusion and lastly alienation let her spin out of control, allowing only “herself” to survive. Unlike in The Spiral Staircase, the interior is totally unthreatening, which makes Terry’s murderous lust even more terrifying.

TIME OUT OF MIND (1946/7) is more melodrama than Noir. Chris Fortune (Robert Hutton), the son of a heartless and ambitious shipping tycoon, falls in love with the servant girl Kate (Phyllis Calvert). But in 19th century New England, this was not the social norm. Kate encourages Chris to marry a lady of his class, who turns out to be a beast and drives Chris more into alcohol dependency. Chris fancies himself as a composer, but only Kate believes in his talent. The Noir aspect is the family constellation: Chris is obviously weak, and his overbearing father (Leo G. Carroll) rules over his life. More to the point, Chris’s sister Rissa (Ella Raines) seemingly protects her younger brother, but is in reality totally obsessed by him. She represents the semi-incestuous theme running, not only through Siodmak’s, noir films.

TIME OUT OF MIND (1946/7) is more melodrama than Noir. Chris Fortune (Robert Hutton), the son of a heartless and ambitious shipping tycoon, falls in love with the servant girl Kate (Phyllis Calvert). But in 19th century New England, this was not the social norm. Kate encourages Chris to marry a lady of his class, who turns out to be a beast and drives Chris more into alcohol dependency. Chris fancies himself as a composer, but only Kate believes in his talent. The Noir aspect is the family constellation: Chris is obviously weak, and his overbearing father (Leo G. Carroll) rules over his life. More to the point, Chris’s sister Rissa (Ella Raines) seemingly protects her younger brother, but is in reality totally obsessed by him. She represents the semi-incestuous theme running, not only through Siodmak’s, noir films.

CRISS CROSS (1949) is perhaps Siodmak’s most personal Noir. Reworking elements of The Killers – and casting Burt Lancaster again in the role of the obsessed lover -, CRISS CROSS is the story of an “amour fou”, its emotional intensity on par with Tourneur’s classic Out of the Past. Steve Thompson (Lancaster) is still in love with his ex wife Anna (Yvonne De Carlo), who now lives with the gangster Slim Dundee (Dan Duryea). But when the two of them meet in a bar, the whole things starts up again. Dundee surprises them, Thompson comes up with an excuse: he needs Dundee’s help for an armed car robbery. But Dundee is suspicious: he and his gang kill Thompson’s partner and wound him after the robbery. When Anna goes missing with the money, Dundee suspects the couple have double-crossed him. Dundee has Thompson abducted, but Thompson bribes his captors and finds Anna. She is terrified by the thought that Dundee will find them and wants to abandon the wounded Steve, but Dundee arrives and shoots them both, before running towards the police. The final scene, when Anna’s and Steve’s bodies fall literally into each other, bullets flying as the police siren’s grow louder, is the apotheosis of everything that’s gone on since the scene in the bar. From then on, in true Noir fashion, all is told in flashbacks and voice-over narration. Anna is the quintessential Noir heroine, telling Steve: “All those things which have happened we’ll forget it. You see, I make you forget it. After it’s done, after it’s all over and we are safe, it will be just you and me. The way it should’ve been all along from the start”. CRISS CROSS is my personal favourite: dark, expressionistic, melancholic and wonderfully doomed.

THE GREAT SINNER (1948/9) is an awkward mixture of high literature and low-brow melodrama. Based partly on Dostoyevsky’s novel “The Gambler” and some autobiographical details of this author, Siodmak struggles to bring this expensive “A-picture” to life. The stars Gregory Peck (Fedya) and Ava Gardener (Pauline Ostrovsky) – in the first of three collaborations – do their best, but Christopher Isherwood’s script is a hotchpotch of the sensational and sentimental, tragic events unfold fast and furiously, logic and characterisation falling by the wayside. Told in a long flash-back, Pauline receives a manuscript from the dying writer Fedya, in which he tells the story of their first meeting in 1860 in Wiesbaden. Then, Fedya met Pauline on a train journey from Paris to Moscow, but follows her to the casino in Wiesbaden, to study the effects of gambling on the whole Ostrovsky clan. When Pitard, a gambler and friend of Pauline, steals Fedya’s money, the latter tries to save Pitard from his fate, and gives him the money so he can leave the city. But Pitard loses in the casino and shoots himself. Strangely enough, Fedya, who has fallen in love with Pauline, also becomes addicted to gambling – but telling himself, that he wants to win the money, so that Pauline’s father can pay back his debts to the casino owner Armand, and thus free Pauline from the engagement to the ruthless tycoon. But after some early success, Fedya looses heavily, tries to in vain to pawn a religious medal, which belongs to Pauline; finally, he wants to commit suicide, before he looses consciousness. Recovered, he finishes his novel and Pauline forgives him. In spite of a strong supporting cast including Ethel Barrymore, Melvin Douglas, Agnes Moorehead and Walter Huston, THE GREAT SINNER flopped at the box-office, having cost 20 m Dollar in today’s money, it lost 8 m Dollar. Siodmak, according to Gregory Peck, did not enjoy the responsibility of the big budget production, “he looked like a nervous wreck”.

With THE FILE ON THELMA JORDON (1949) Siodmak returned to the safe ground of Noir films. Thelma (Barbara Stanwyck) is unhappily married to Tony Laredo (Richard Rober), but is attracted to his animalistic sex-appeal. When she discusses burglaries at her wealthy aunt’s house, where she also lives, with assistant district attorney Cleve Marshall (Wendell Correy), the two fall in love. When the aunt is killed, and a necklace stolen, Thelma is the main suspect, because Tony has been away to Chicago. Thelma is put on trial, and Cleve pays her lawyer and plans the trial strategy with him, even though he has learned about Thelma’s past, and is convinced that she is the murderer. The aunt’s butler has seen a stranger at the crime scene, but did not recognise him. Thelma, who knows that the person is Cleve, does not give his name away. She is aquitted and wants to leave town with Tony, when Cleve confronts them. Tony beats Cleve up and the couple flee, but Thelma causes an accident on purpose, in which both are killed – but not before she has confessed to the murder. In spite of this, Cleve’s career and marriage is ruined. THE FILE ON THELMA JORDON is a neat reversal on Double Indemnity, which also starred Stanwyck as the Queen of all femme fatales. But here, Thelma and Cleve really love each other, and Thelma pays for her crime with her life, and Cleve will be ostracised by society for a long time. Whilst Wilder’s couple was evil from the beginning, Siodmak gives his lovers a much more human touch. THE FILE ON THELMA JORDON was Robert Siodmak’s last American Film Noir. He would later direct two more films, which are in certain ways close to the subgenre; but he would never again achieve the greatness of his American Film Noir cycle, even his directing output would run to another 18 films.

With THE FILE ON THELMA JORDON (1949) Siodmak returned to the safe ground of Noir films. Thelma (Barbara Stanwyck) is unhappily married to Tony Laredo (Richard Rober), but is attracted to his animalistic sex-appeal. When she discusses burglaries at her wealthy aunt’s house, where she also lives, with assistant district attorney Cleve Marshall (Wendell Correy), the two fall in love. When the aunt is killed, and a necklace stolen, Thelma is the main suspect, because Tony has been away to Chicago. Thelma is put on trial, and Cleve pays her lawyer and plans the trial strategy with him, even though he has learned about Thelma’s past, and is convinced that she is the murderer. The aunt’s butler has seen a stranger at the crime scene, but did not recognise him. Thelma, who knows that the person is Cleve, does not give his name away. She is aquitted and wants to leave town with Tony, when Cleve confronts them. Tony beats Cleve up and the couple flee, but Thelma causes an accident on purpose, in which both are killed – but not before she has confessed to the murder. In spite of this, Cleve’s career and marriage is ruined. THE FILE ON THELMA JORDON is a neat reversal on Double Indemnity, which also starred Stanwyck as the Queen of all femme fatales. But here, Thelma and Cleve really love each other, and Thelma pays for her crime with her life, and Cleve will be ostracised by society for a long time. Whilst Wilder’s couple was evil from the beginning, Siodmak gives his lovers a much more human touch. THE FILE ON THELMA JORDON was Robert Siodmak’s last American Film Noir. He would later direct two more films, which are in certain ways close to the subgenre; but he would never again achieve the greatness of his American Film Noir cycle, even his directing output would run to another 18 films.

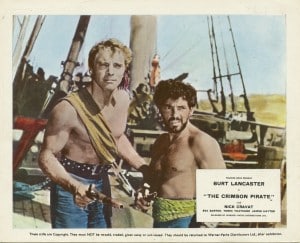

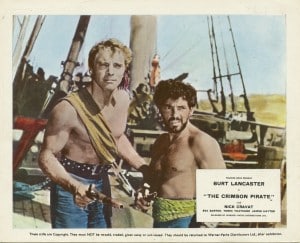

In the THE CRIMSON PIRATE (1951/2) Siodmak was reunited with Burt Lancaster, who also produced the film. Set in the late 18th century in the Caribbean, Captain Vallo (Lancaster), is a pirate, who tries to make money from selling weapons to the rebels on the island of Cobra, lead by El Libre (Frederick Leicester). On the island, Vallo falls in love with El Libre’s daughter Conseuela (Eva Bartok). Later he has to rescue her father, and support the revolution – even against the wishes of his fellow pirates, who do not see the reason for such a good deed – since it is totally unprofitable! In a stormy finale with tanks, TNT, machine guns and an outstanding colourful airship, our hero, now in drag, wins the revolution and Consulea’s heart. What is most surprising is the humour and lightheartedness of the production. Everything is told tongue-in-cheek, the action scenes are overwhelming and Lancaster (the ex-circus acrobat) dominates the film with his stunts. It seems hardly credible Robert Siodmak, creator of gloom and doom, dark shadows and even darker hearts, would be responsible for such an uplifting and hilarious spectacle, 15 years before Louis Malle’s equally enchanting “Viva Maria!”. Ken Adam, the future “Bond” production designer, earned one of his first credits for this film.

In the THE CRIMSON PIRATE (1951/2) Siodmak was reunited with Burt Lancaster, who also produced the film. Set in the late 18th century in the Caribbean, Captain Vallo (Lancaster), is a pirate, who tries to make money from selling weapons to the rebels on the island of Cobra, lead by El Libre (Frederick Leicester). On the island, Vallo falls in love with El Libre’s daughter Conseuela (Eva Bartok). Later he has to rescue her father, and support the revolution – even against the wishes of his fellow pirates, who do not see the reason for such a good deed – since it is totally unprofitable! In a stormy finale with tanks, TNT, machine guns and an outstanding colourful airship, our hero, now in drag, wins the revolution and Consulea’s heart. What is most surprising is the humour and lightheartedness of the production. Everything is told tongue-in-cheek, the action scenes are overwhelming and Lancaster (the ex-circus acrobat) dominates the film with his stunts. It seems hardly credible Robert Siodmak, creator of gloom and doom, dark shadows and even darker hearts, would be responsible for such an uplifting and hilarious spectacle, 15 years before Louis Malle’s equally enchanting “Viva Maria!”. Ken Adam, the future “Bond” production designer, earned one of his first credits for this film.

It will never be absolutely clear why Robert Siodmak decided to leave Hollywood after he finished THE CRIMSON PIRATE, to work again in Germany (with a one-film stop in France, so as to repeat his journey of the thirties backwards). In the USA, he was offered a lucrative six-film deal and had shown with his last film, that he could now also handle big productions successfully. There are rumours of pending HUAC hearings, because of his friendship with Charles Spencer Chaplin, but Siodmak himself never mentioned these as a reason for the return to his homeland. Rather like Fritz Lang and Edgar Ulmer, it can only be assumed that “Heimweh” was the reason for Siodmak’s return. True, he lived in Ascona, Switzerland, but he worked nearly exclusively in Germany. What he, and other “Remigrants” did not reckon with, was the political and cultural climate in the Federal Republic of Germany. When these directors had left Germany, the Nazis had just started the transformation of the country. But in the early fifties, the democracy of the country was not chosen, but forced on the population by the Allies. Old Nazis were still in many powerful positions, and the majority of the population still grieved, full of self-pity, about their defeat. The Third Reich, and particularly the Holocaust, were more or less Taboo, both in daily life and in all cultural referenced. The film industry also suffered from the lack of a new beginning; even Veit Harlan, director of Jud Süss, was allowed to restart his career. It is no co-incidence that neither Lang or Ulmer produced anything notable after their return.

The same can be said for Robert Siodmak, with one exception: THE DEVIL STRIKES AT NIGHT (NACHTS WENN DER TEUFEL KAM), which he directed in 1957 was, deservedly, nominated for the “Oscar” as “Best foreign film”. Set during WWII in Hamburg, the film tells the story of the serial killer Bruno Lüdke (Mario Adorf). When caught by inspector Kersten (Claus Holm), the latter’s superior, the Gestapo Officer Rossdorf (Hannes Messmer) points out that another man had already been ‘convicted’: Willi Keun (Wolfgang Peters), a small-time party member, had “been shot whilst escaping” – without informing the population about the murders, since just a monstrous criminal did not fit in with ruling ideology of the Aryan supremacy. Both, police man and Gestapo officer, now have the difficult task to start to convince the authorities that a German serial killer was on the loose for over a decade. Both will be sent to the Eastern front, to cover up the case. The film is based on real events, Bruno Lüdke (1908-1944) was mentally retarded, but may have confessed to more murders than he actually committed – to clear up unsolved murder cases. Siodmak re-creates the atmosphere of his best Noir films: the city is darkened, the image dissolves from an omniscient perspective to a particular one – particularly in the scene where Lüdke is caught in the headlights of a car. Fear and excitement permeate like a black stain throughout. Kesten’s obsession with the case create a fragmented world, where the images seem to splinter. Chaos rules, and nobody seems to be safe: the hunt for Lüdke, which frames the film, is shown like a haunting parable on the destructive nature of the 3rd Reich. Unfortunately, Siodmak fell short of this standard in the other 12 films directed in West Germany between 1955 and 1969.

The same can be said for Robert Siodmak, with one exception: THE DEVIL STRIKES AT NIGHT (NACHTS WENN DER TEUFEL KAM), which he directed in 1957 was, deservedly, nominated for the “Oscar” as “Best foreign film”. Set during WWII in Hamburg, the film tells the story of the serial killer Bruno Lüdke (Mario Adorf). When caught by inspector Kersten (Claus Holm), the latter’s superior, the Gestapo Officer Rossdorf (Hannes Messmer) points out that another man had already been ‘convicted’: Willi Keun (Wolfgang Peters), a small-time party member, had “been shot whilst escaping” – without informing the population about the murders, since just a monstrous criminal did not fit in with ruling ideology of the Aryan supremacy. Both, police man and Gestapo officer, now have the difficult task to start to convince the authorities that a German serial killer was on the loose for over a decade. Both will be sent to the Eastern front, to cover up the case. The film is based on real events, Bruno Lüdke (1908-1944) was mentally retarded, but may have confessed to more murders than he actually committed – to clear up unsolved murder cases. Siodmak re-creates the atmosphere of his best Noir films: the city is darkened, the image dissolves from an omniscient perspective to a particular one – particularly in the scene where Lüdke is caught in the headlights of a car. Fear and excitement permeate like a black stain throughout. Kesten’s obsession with the case create a fragmented world, where the images seem to splinter. Chaos rules, and nobody seems to be safe: the hunt for Lüdke, which frames the film, is shown like a haunting parable on the destructive nature of the 3rd Reich. Unfortunately, Siodmak fell short of this standard in the other 12 films directed in West Germany between 1955 and 1969.

In 1959 Siodmak worked in the Elstree-Borehamwood studios, to direct THE ROUGH AND THE SMOOTH, based on the novel by Robin Maugham. Robert Cecil Romer, 2nd Viscount Maugham, nephew of Somerset Maugham, was the enfant terrible of his family. Socialist and self-confessed homosexual, he was a very underrated novelist: The Servant, filmed in 1963 by Joseph Loosey, with Dirk Bogarde in the title role, is one of the classics of British post-WWII cinema. THE ROUGH AND THE SMOOTH shows similarities: Mike Thompson (Tony Britton), an archeologist, is engaged to Margaret (Natasha Parry), the daughter of his boss, who finances his work. Mike feels trapped in a loveless relationship, and falls for Ila Hansen (Nadja Tiller), a young and attractive woman. But she has a secret: not only is she in cahoots with the tough gangster Reg Barker (William Bendix), but there is a third man in her life, who has a hold over her. After Barker commits suicide, driven by Hansen’s demands, the latter tries also to blackmail Mike and Margaret. The ending is quiet original. There are very dark undertones, particularly for the late 50s, when Ila comments: “I don’t cry much, I have been hurt a lot”. THE ROUGH AND THE SMOOTH is a subversive film considering the context of its period. The camera pans over stultified Britain of the last 50s, where there seems to be no middle-ground between boring respectability and outright perversion. When the two worlds collide, the conflict is fought on both sides with grim, violent determination. With THE ROUGH AND THE SMOOTH, Siodmak, would, for the last time, come close to his American Noir films, for which he was called “Prince of the Shadows”: referring not only to the quality of the images, but also to a society, where, to quote Brecht, “we are only aware of the ones in the light, the ones in the shadows, we don’t see”. Robert Siodmak made sure that the ones in the shadows played the major roles in his Films Noir career. Andre Simonoviescz ©

In 1959 Siodmak worked in the Elstree-Borehamwood studios, to direct THE ROUGH AND THE SMOOTH, based on the novel by Robin Maugham. Robert Cecil Romer, 2nd Viscount Maugham, nephew of Somerset Maugham, was the enfant terrible of his family. Socialist and self-confessed homosexual, he was a very underrated novelist: The Servant, filmed in 1963 by Joseph Loosey, with Dirk Bogarde in the title role, is one of the classics of British post-WWII cinema. THE ROUGH AND THE SMOOTH shows similarities: Mike Thompson (Tony Britton), an archeologist, is engaged to Margaret (Natasha Parry), the daughter of his boss, who finances his work. Mike feels trapped in a loveless relationship, and falls for Ila Hansen (Nadja Tiller), a young and attractive woman. But she has a secret: not only is she in cahoots with the tough gangster Reg Barker (William Bendix), but there is a third man in her life, who has a hold over her. After Barker commits suicide, driven by Hansen’s demands, the latter tries also to blackmail Mike and Margaret. The ending is quiet original. There are very dark undertones, particularly for the late 50s, when Ila comments: “I don’t cry much, I have been hurt a lot”. THE ROUGH AND THE SMOOTH is a subversive film considering the context of its period. The camera pans over stultified Britain of the last 50s, where there seems to be no middle-ground between boring respectability and outright perversion. When the two worlds collide, the conflict is fought on both sides with grim, violent determination. With THE ROUGH AND THE SMOOTH, Siodmak, would, for the last time, come close to his American Noir films, for which he was called “Prince of the Shadows”: referring not only to the quality of the images, but also to a society, where, to quote Brecht, “we are only aware of the ones in the light, the ones in the shadows, we don’t see”. Robert Siodmak made sure that the ones in the shadows played the major roles in his Films Noir career. Andre Simonoviescz ©

MASTER OF SHADOWS | A RETROSPECTIVE OF ROBERT SIODMAK

Masters of Cinema home video release of CRISS CROSS; Robert Siodmak’s influential film noir masterpiece; to be released on 22 June 2020.

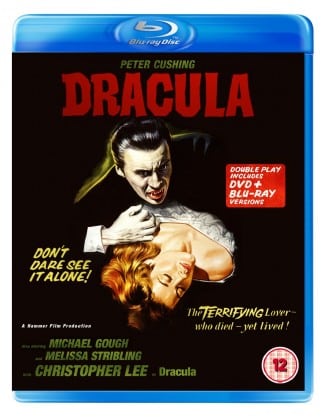

Atmospherically directed by Hungarian Peter Sasdy, and adapted for the screen by Anthony Hinds – stepping in due to budgetary constraints under the pseudonym of John Elder (he told his neighbours he was a hairdresser to avoid publicity throughout his entire career) this outing actually broadens the storyline into a damning social satire of Victorian repression and upper class ennui. The eclectic cast has Christopher Lee, Geoffrey Keen and Gwen Watford and sees three distinguished English gentlemen (Keen, Peter Sallis and John Carson) descend into Satanism, for want of anything better to do, accidentally killIng Dracula‘s sidekick Lord Courtly (Ralph Bates), in the process. As an act of revenge the Count vows they will die at the hands of their own children. But Lee actually bloodies the waters in the second half, swanning in glowering due to his lack of a domineering role in the proceedings.

Atmospherically directed by Hungarian Peter Sasdy, and adapted for the screen by Anthony Hinds – stepping in due to budgetary constraints under the pseudonym of John Elder (he told his neighbours he was a hairdresser to avoid publicity throughout his entire career) this outing actually broadens the storyline into a damning social satire of Victorian repression and upper class ennui. The eclectic cast has Christopher Lee, Geoffrey Keen and Gwen Watford and sees three distinguished English gentlemen (Keen, Peter Sallis and John Carson) descend into Satanism, for want of anything better to do, accidentally killIng Dracula‘s sidekick Lord Courtly (Ralph Bates), in the process. As an act of revenge the Count vows they will die at the hands of their own children. But Lee actually bloodies the waters in the second half, swanning in glowering due to his lack of a domineering role in the proceedings.

Dresden 1918, Robert Siodmak left his upper-middle class, orthodox Jewish home in this epicentre of European modern art, to join a theatre touring company. He was 18, and this was the first of many radical changes that would see him becoming a pioneer of film noir, and directing 56 feature films fraught with (anti)heroes who are morose, malevolent, violent and generally downbeat (spoilers).

Dresden 1918, Robert Siodmak left his upper-middle class, orthodox Jewish home in this epicentre of European modern art, to join a theatre touring company. He was 18, and this was the first of many radical changes that would see him becoming a pioneer of film noir, and directing 56 feature films fraught with (anti)heroes who are morose, malevolent, violent and generally downbeat (spoilers).

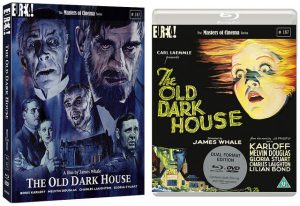

Dir: James Whale | Wri: Benn Levy/J B Priestley | Cast: Boris Karloff| Charles Laughton | Eva Moore | Gloria Stuart | Melvyn Douglas| Raymond Massey | Horror / Comedy |US 75′

Dir: James Whale | Wri: Benn Levy/J B Priestley | Cast: Boris Karloff| Charles Laughton | Eva Moore | Gloria Stuart | Melvyn Douglas| Raymond Massey | Horror / Comedy |US 75′

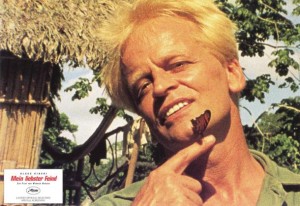

There is no filmmaker like Edgar Pêra (b.1960). His work may be an acquired taste but it is always inventive and Avant-garde referencing his heroes in creative ways and keeping the past alive. The Portuguese auteur often pays tribute to Dziga Vertov, Branquinho da Fonseca and Fernando Pessoa – but always in an ingenious way – transforming their ideas into bizarre and refreshing features, some will screen in a retrospective at the

There is no filmmaker like Edgar Pêra (b.1960). His work may be an acquired taste but it is always inventive and Avant-garde referencing his heroes in creative ways and keeping the past alive. The Portuguese auteur often pays tribute to Dziga Vertov, Branquinho da Fonseca and Fernando Pessoa – but always in an ingenious way – transforming their ideas into bizarre and refreshing features, some will screen in a retrospective at the  Edgar Henrique Clemente Pêra first studied psychology, but soon realised his vocation in Film at the Portuguese National Conservatory, currently

Edgar Henrique Clemente Pêra first studied psychology, but soon realised his vocation in Film at the Portuguese National Conservatory, currently

Dir: Maurice Tourneur | Writer: Jean-Paul Le Chanois | Cast: Pierre Frenay, Josseline Gaël | Fantasy Horror | France 78′

Dir: Maurice Tourneur | Writer: Jean-Paul Le Chanois | Cast: Pierre Frenay, Josseline Gaël | Fantasy Horror | France 78′