BACKYARD CINEMA at MERCATO METROPOLITANO is the latest immersive cinema space where its scene shifting theme has now found a permanent home in the Elephant & Castle venue. From now on the ambiance transform seasonally and the latest incarnation is Miami Beach with its own beach bar with delicious Italian fare to feast on. To feel the sand between your toes, flip-flops are provided. MERCATO METROPOLITANO is at Elephant and Castle. The full film programme is here.

BACKYARD CINEMA at MERCATO METROPOLITANO is the latest immersive cinema space where its scene shifting theme has now found a permanent home in the Elephant & Castle venue. From now on the ambiance transform seasonally and the latest incarnation is Miami Beach with its own beach bar with delicious Italian fare to feast on. To feel the sand between your toes, flip-flops are provided. MERCATO METROPOLITANO is at Elephant and Castle. The full film programme is here.

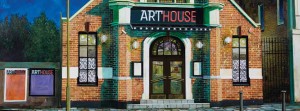

ARTHOUSE CROUCH END, 159 Tottenham Lane N8 9BT

An intimate child-friendly venue (ever been locked in with a two-year old tantrum) that offers all the latest arthouse films just around the corner for Crouch End and Stroud Green dwellers. Membership scheme available.

An intimate child-friendly venue (ever been locked in with a two-year old tantrum) that offers all the latest arthouse films just around the corner for Crouch End and Stroud Green dwellers. Membership scheme available.

GREENWICH PICTUREHOUSE, 180 Greenwich High Road Greenwich London SE10 8NN

Showing all the latest indie and arthouse fare – Box Office Number: 0871 902 5732 (calls cost 13p per minute plus your telephone company’s access charge). Membership scheme available

Email: greenwich@picturehouses.co.uk General Manager:

Designed for the modern filmgoer, CURZON ALDGATE is a new four-screen cinema in London’s culturally vibrant East End. Curzon will bring their renowned programming to the venue – ranging from the best of Hollywood to critically acclaimed independent cinema from all over the world. Curzon Cult Membership is now available £350, buys free tickets for a year!

Designed for the modern filmgoer, CURZON ALDGATE is a new four-screen cinema in London’s culturally vibrant East End. Curzon will bring their renowned programming to the venue – ranging from the best of Hollywood to critically acclaimed independent cinema from all over the world. Curzon Cult Membership is now available £350, buys free tickets for a year!

THE EXHIBIT | BALHAM | 12 BALHAM STATION ROAD | SW12 8SG| An arts venue with an American bar and restaurant here for your entertainment. From art-house to retro films, weekend comedy to life drawing classes and art exhibitions, in an ever-changing revolving programme.

THE EXHIBIT | BALHAM | 12 BALHAM STATION ROAD | SW12 8SG| An arts venue with an American bar and restaurant here for your entertainment. From art-house to retro films, weekend comedy to life drawing classes and art exhibitions, in an ever-changing revolving programme.

The Exhibit has a state-of-the-art cinema with 12 sofas for two and great cocktails, bottomless brunch (clearly guaranteed not to add to your bottom). There are flexible spaces available to hire and even Speed Dating for those who prefer to meet face to face.

Also on offer: New Year’s Eve Champagne and Glitter Party and a selection of Christmas-themed films.

THE EVERYMAN KINGS CROSS | Handyside Street | London N1

Independent group The Everyman bijou cinema opens in the heart of the 67-acre King’s Cross estate in mid July 2016 with three screens in an office building known as R7 and locate adjacent to the University of the Arts London.

The Everyman Cinema now includes 16 venues, ranging from the iconic 100-year-old Screen on the Green to the latest space in Crossrail Place, Canary Wharf. This latest boutique venue will offer the service of food and drink and an auteur-driven selection of the latest releases together with more mainstream fare and exclusive live events. (photo: Nunzio Prenna ).

THE REGENT STREET CINEMA | Regent Street | London W1

THE REGENT STREET CINEMA | Regent Street | London W1

The Regent Street Cinema was re-opened by the University of Westminster in May 2015, reinstating one of the most historic cinemas in Britain to its former grandeur. Built in 1848, the cinema showcased the Lumière brothers’ Cinematographe to a paying audience, and , as the curtain fell, British cinema was born. After serving as a lecture theatre by the university since 1980, it was restored into a working cinema featuring a state-of-the-art auditorium as well as an inclusive space for learning. The cinema is one of the few in the country to show 16mm and 35mm film, as well as the latest in 4K digital film. You can also experience double bills, world cinema and classic movies in its classic environment.

A fully stocked bar offers spirits, wines and snacks and caters for more filling alternatives (coming soon) to keep you going through the double bills. The cinema is also available for hire and private screenings. Listings information here.

THE ELECTRIC CINEMA, BIRMINGHAM | Britain second largest city Birmingham, is home to THE ELECTRIC CINEMA, the UK’s oldest working cinema and also one of its most cosy and comfortable. Opening its doors in 1909, an era when most people were without electricity at home, the mysterious invisible power source graced the picture house with an exotic allure and silent films were accompanied by a live piano score. Sound arrived in 1930 and the cinema showed news reels from Pathe and British Movietone. The first to shoot and edit its own regional news, the Cinema was revamped by Birmingham businessman Joseph Cohen, who owned 50 other cinemas during his heyday with Jacey Cinema.

THE ELECTRIC CINEMA, BIRMINGHAM | Britain second largest city Birmingham, is home to THE ELECTRIC CINEMA, the UK’s oldest working cinema and also one of its most cosy and comfortable. Opening its doors in 1909, an era when most people were without electricity at home, the mysterious invisible power source graced the picture house with an exotic allure and silent films were accompanied by a live piano score. Sound arrived in 1930 and the cinema showed news reels from Pathe and British Movietone. The first to shoot and edit its own regional news, the Cinema was revamped by Birmingham businessman Joseph Cohen, who owned 50 other cinemas during his heyday with Jacey Cinema.  Today THE ELECTRIC CINEMA offers the latest indie and mainstream fare. The current manager Tom Lawes added a second screen and a basement recording studio. Relax in its leather sofas and velvet armchairs and enjoy screenings every day of the year (except Christmas Day). Enjoy the Art Deco Bar which serves a variety of craft beers, wines and champagne that you can drink during the screening along with homemade cakes, snacks and ice cream sourced from local independent suppliers – our favourite flavour Honeycomb toffee.

Today THE ELECTRIC CINEMA offers the latest indie and mainstream fare. The current manager Tom Lawes added a second screen and a basement recording studio. Relax in its leather sofas and velvet armchairs and enjoy screenings every day of the year (except Christmas Day). Enjoy the Art Deco Bar which serves a variety of craft beers, wines and champagne that you can drink during the screening along with homemade cakes, snacks and ice cream sourced from local independent suppliers – our favourite flavour Honeycomb toffee.

A pioneering partnership between Goldsmiths, University of London and Curzon Cinemas is to bring full-time cinema to Lewisham after a gap of 15 years. CURZON GOLDSMITHS will show films to the public on weekday evenings and all day at weekends. The revamped screening facilities in the Richard Hoggart Building will be used for teaching during weekdays, with the facility available for exclusive use by Goldsmiths students and staff until 6pm Monday to Friday.

A pioneering partnership between Goldsmiths, University of London and Curzon Cinemas is to bring full-time cinema to Lewisham after a gap of 15 years. CURZON GOLDSMITHS will show films to the public on weekday evenings and all day at weekends. The revamped screening facilities in the Richard Hoggart Building will be used for teaching during weekdays, with the facility available for exclusive use by Goldsmiths students and staff until 6pm Monday to Friday.

The cinema on the university’s New Cross campus is due to open at the end of January 2016. Programming at the 101-seat venue which includes space for two wheelchair users will follow Curzon’s mix of the best in cinema from across the globe as well as documentary and special director Q&As.

THE CURZON SCREEN AT HAM YARD HOTEL | SOHO W1

THE CURZON SCREEN AT HAM YARD HOTEL | SOHO W1

A 2015 newcomer to the INDEPENDENT CINEMA GUIDE is this latest Curzon Screen at Ham Yard Hotel, in the heart of Soho, W1. The hotel is independently run by a British couple as part of the Firmdale Hotel Group and lavishly decorated with contemporary artworks, completing the cool vibe. Enjoy cocktails or the latest in international cuisine before going down to the comfortable cinema, a state-of-the-art affair, which features Dolby sound and an XpanD Digital 3D capable screen. The latest releases, selected from CURZON’s eclectic brand of international arthouse titles and cult classics, ensure that cineastes will not be disappointed. Ham Yard Hotel’s colourful Dive Bar is open exclusively to Curzon cinema ticket holders for pre- and post-film drinks. No membership required, just turn up at the door.

THE ELECTRIC CINEMA- Shoreditch (Formerly the AUBIN CINEMA)

Run in conjunction with Shoreditch House private members’ club, the Electric Cinema provides an unrivalled level of comfort and style for up to 45 cinema-goers offering a broad range of quality mainstream and art house films and features popular titles that are critically acclaimed. A venue for popular events including the. ukfilmfestival.com

CATERING – Shoreditch House has a comprehensive bar and gourmet restaurant.

SEATING/COMFORT – seats 45- Velvet sofas and chairs with plumped cushions!

TECHNICALS – 35mm film projection. Sky HD, DVD, BluRay video projection. DigiBeta, HD-D5, HDCAM-SR, HDCAM, DVCAM, HDDV. All aspect ratios. Dolby.

DESIGN – Converted warehouse completely and stylishly modernized.

TICKETS – By phone or online The Box Office is open Monday to Saturday 3pm – 10pm and Sunday 11am-9pm.

SPECIALS – Classic cinema events and monthly ticket giveaways by Twitter.

Map and Directions

Box Office: 0845 604 8486

http://www.aubincinema.com/about/booking-info/

THE BIRKBECK CINEMA

THE BIRKBECK CINEMA

41 Gordon Square, London WC1H OPD

The Birkbeck is a hidden gem. Tucked away in the basement of number 41, Gordon Square, Bloomsbury, the area affords ample parking for evening and weekend screenings and with 70 seats, the cinema has recently hosted the OPEN CITY DOCS FEST and is also available for hire.

CURZON BLOOMSBURY – BRUNSWICK CENTRE, BLOOMSBURY, WC1

Boasting a fabulous minimalist refurbishment by architect Takero Shimazaki with furniture by Eileen Grey, the newly-named Curzon Bloomsbury is increasing from 2 screens to 6. Part of the Curzon group, which includes Curzon’s Mayfair, Soho, Ham Yard, Chelsea, and Richmond, this state of the art complex will continue to showcase quality arthouse fare as a popular choice for cineastes wanting to avoid the West End. Situated in the revamped Brunswick Centre, opposite Russell Square tube. 6 new screens include the RENOIR of 149 seats, LUMIERE (30 seats); MINEMA (28 seats); PHOENIX (28 seats); Plaza (30 seats); BERTHA DOCHOUSE (55 seats) dedicated to documentaries. The more bijoux screens are ideal for private event hire, but avoid the aisle seats in the Phoenix if you are sensitive to overhead lighting.

CATERING: Bar at Level 1 accommodating up to 148 guests. Additional bars on the lower levers. SEATING/COMFORT – Comfortable grey velvet reclining seating.

CATERING: Bar at Level 1 accommodating up to 148 guests. Additional bars on the lower levers. SEATING/COMFORT – Comfortable grey velvet reclining seating.

TECHNICALS – Dolby Atmos; 4K HD video projection, DVD, data, mini DV All aspect ratios. Spotlight. Radio microphone..

SPECIALS – Q & As, Bertha DocDays, Met Opera Live, Opera and Ballet screened and Special Previews. Also sells a good selection of arthouse DVD/blu.

The Brunswick, London, WC1N 1AW Map; Tube: Russell Square

Recorded Information and Booking Line: 0330 500 1331

CINE LUMIÈRE – SOUTH KENSINGTON

Part of the Institut Français, with its beautiful Deco design, opened in 1939 in the heart of South Kensington, round the corner from the Natural History Museum and the V&A. An airy marble foyer and sweeping staircase up to the cinema.

CAFE – As you might expect with a French cinema complex, the café is probably the best of any arthouse cinema you might visit, although it is also pricey. Les Salons can hold 60 people seated, for functions.

TECHNICALS – 241 seats. 35mm film projection. 2K HD video projection. Beta SP and, DVD, laptops. All aspect ratios. Spotlight. Mixing desk. Cabled microphones. The Mediatheque can cater for 80.

DESIGN – Improvements to the accessibility of the Institut français’ 17 Queensberry Place site are ongoing. Access to the ground floor foyer/reception/bistro is by ramp; the library and cinema on the first floor can now be accessed by lift..

DESIGN – Improvements to the accessibility of the Institut français’ 17 Queensberry Place site are ongoing. Access to the ground floor foyer/reception/bistro is by ramp; the library and cinema on the first floor can now be accessed by lift..

TICKETS – £1.50 ontop for online ticket bookings, unless a member of the Institute. Tube: South Kensington Station. Box Office: 020 7871 3515

SHORTWAVE – BERMONDSEY

Independent cinema and café based in Bermondsey Square, just off the Tower Bridge Road, screening arthouse, classic and indie film, as well as championing emerging film talent. Cinema opened in April 2009. ‘Shortwave’ itself launched in 1999, with the objective of promoting emerging film and video artists using events.

CATERING – Café and bar, supplies fresh local cakes and snacks. Organic Fairtrade coffee, tea, etc. Alcohol licence. Free wireless Internet. Outside seating.

SEATING/COMFORT – modern auditorium, red velvet seating.

TECHNICALS – 52 seats. 35mm film projection. Surround Sound and HD projection.

DESIGN – Modern build. Fully disabled access.

SPECIALS – Outdoor Cinema in the Aylesbury Estate, Walworth, managing the Bermondsey Street Festival and the Elephant and Castle Arts Festival ‘Elefest’, curates the Portobello Film & Video Arts Festival.

10 Bermondsey Square

London SE1 3UN

TRICYCLE CINEMA – KILBURN

TRICYCLE CINEMA – KILBURN

Open seven days a week, the Tricycle not only offers an independent 300 seat cinema and also a unique 235 seat theatre, bar and café, plus three rehearsal spaces that are often used for our community and education work, Tricycle shows, or external hires.CATERING – Fully licensed bar and café. Caribbean food available pre-screening.

SEATING/COMFORT – 300 seat comfortable cinema.

TECHNICALS – 251 seats. 35mm film projection. 2K HD video projection.

DESIGN – Modern build, fully accessible.

TICKETS – £0.50 fee per online ticket

SPECIALS – Parent and baby Screenings, family screenings, Q& A’s with notable directors and actors, LFF, Images of Black Women Film Festival, UK Jewish Film Festival, DocHouse and the Kilburn Film Festival, Portuguese. 269 Kilburn High Road, London NW6 7JR; Nearest tube: Kilburn (Jubilee Line)Nearest overground: BrondesburyBox office: 020 7328 1000

RITZY – BRIXTON Brixton Oval, Coldharbour Lane, SW2 1JG, UK

In the livewire centre of Brixton and part of the PICTUREHOUSE group that includes Picturehouses in Clapham, Stratford, Hackney, Greenwich and The Gate in Notting Hill. The building originally opened in 1911 and has gone through several incarnations, before its current one, now a multiscreen, with an additional space for live performances.

A mix of mainstream, Bollywood, classic and arthouse film.

CATERING – Upstairs bar open 7 days a week with a range of cuisine made by onsite chefs. Exterior seating is provided in the large open air bar in the square.

CATERING – Upstairs bar open 7 days a week with a range of cuisine made by onsite chefs. Exterior seating is provided in the large open air bar in the square.

SEATING/COMFORT – 5 screens, seating 52, 111,113, 181 and 352. Adequate seating.

TECHNICALS – 35mm film projection. HD video projection. DCP, DVD/BluRay, BetaSP, Laptop. Mono, Dolby and Dolby SR. All aspect ratios. Two event rooms for hire.

DESIGN – Start of the Twentieth Century, a handsome, prominent building now restored to its original looks.

TICKETS – online or by phone- 0871 902 5739 (10p a minute from a landline)

SPECIALS – Part of the local community, music, film and venue hire. Kids Club, Autism-friendly, Education, Toddler time, Live broadcasts from the National Theatre, Met Opera, and ROH/Bolshoi Ballet productions.

THE TROXY, 490 Commercial Road, London E1

Host to the EAST END FILM FESTIVAL 2013, The Troxy originally opened as a grand cinema in 1933 and was designed to seat an audience of 3520 people. In those days, it showed at the the latest films and featured a floodlit organ which rose from the orchestra pit during the interval, playing hits of the era. the Troxy Wurlitzer is currently undergoing extensive renovation and will soon be re-instated to complete the retro feel of this indie locale.

Regularly hosting stars such as Gracie Fields, Clark Gable and Petula Clark, the first film screened was King Kong and after a run of The Siege of Sydney Street the cinema closed its doors in 1960.The Troxy staff even sprayed perfume during showings to make the cinema-goers feel good. The first film shown was King Kong. The last, in 1960, was “The Siege of Sydney Street”.

The building remained empty and unused for almost three years until 1963, when a tenant was found and the London Opera Centre was created here. Run by the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, the Troxy was used for rehearsals on an extended stage which was an exact size of the Royal Opera House stage. In the 1980s, TROXY became Mecca Bingo, where bingo was held seven days a week, two sessions a day. With the advent of online gambling, Mecca decided to close the operation in 2005.

The current owners, Ashburn Estates, have restored the venue as much as possible to its original glory, whilst incorporating the needs of today’s event requirements. TROXY is now deemed to be London’s most versatile venue, hosting anything from live concerts to company conferences, from indoor sports to weddings film festivals.

For all information regarding tickets please contact: 0844 888 0440 and general inquiries 0207 790 9000.

THE LEXI – KENSAL RISE 194b Chamberlayne Road, Kensal Rise, NW10 3JU (map)

A small but perfectly formed informal cinema that often screen one-offs, classic movies and special interest films.

Located in a smart Church conversation, it’s an intimate space with 75 comfortable seats and individuals armchairs and boasts a unique light sculpture by Bruce Munro. Staffed by an enthusiastic team of volunteers and a small core management team. Carin Von Drehle is especially helpful and happy to help with any enquiries.

Located in a smart Church conversation, it’s an intimate space with 75 comfortable seats and individuals armchairs and boasts a unique light sculpture by Bruce Munro. Staffed by an enthusiastic team of volunteers and a small core management team. Carin Von Drehle is especially helpful and happy to help with any enquiries.

100% of The Lexi’s profits go towards improving the quality of life for the mixed-race people of Lynedoch ECO charity village in Stellenbosch, South Africa.

CATERING – Fully licensed bar. Works with a selection of local caterers to bespoke any event planned.

SEATING/COMFORT – hugely comfortable mixture includes individual chairs.

TECHNICALS – @60 seats. 35mm film projection. 2K HD video projection. Beta SP and Digibeta, DVD, data, mini DV All aspect ratios. Spotlight. Radio microphone. State of the art sound projection.

DESIGN – Small modern space in church conversion.

TICKETS – £1.50 on phone bookings 0871 7042069. Discounts for over 60’s, students and members.

(lines open 9.30am – 8.30pm)

SPECIALS – Valentine Soiree, Kids Club, Parent and Baby, Singalong, outdoor screenings, Easter events, live by satellite, Q&A.

RICHMIX – CINEMA AND ARTS CENTRE – Bethnal Green Road, Shoreditch E1 6LA

RICHMIX – CINEMA AND ARTS CENTRE – Bethnal Green Road, Shoreditch E1 6LA

Rich Mix is a charity and social enterprise that offers a variety of activities from film to live music, theatre and comedy to the East London area. All profits are re-cycled back into the community, nurturing new and local talent. It offers five floors of creativity and no less than three state-of-the-art digital cinema screens showing main releases and indie and arthouse world film.

RICH MIX is open from 9am to 11pm Monday to Friday and 10am to 11pm on weekends and the nearest Mainline station is Shoreditch High Street, on the East London Line or Mainline stations at Liverpool Street, Bethnal Green or Aldgate East.

THE HARINGEY INDIE

THE HARINGEY INDIE

The Haringey Independent Cinema is more of a voluntary cinema club held at the end of each month at the Park View School in West Green Road, London N15. Doors open at 7pm and the film starts at 7.15pm. Tickets are £4/£3 (concessions) and there is an informal invitation to drinks afterwards at KK McCool’s Pub to discuss the film and socialise and meet new people in the area.

The idea is to screen intelligent and thought-provoking features and documentaries sometimes inviting those involved in the project to come along for a chat or Q&A session.

Haringey Independent Cinema is organised by local residents and supported by Haringey Trades Union Council, Woodlands Park Residents’ Association, Chestnuts Northside Residents’ Association and Haringey Solidarity Group.

Other details are available on www.haringey.org.uk/hic/

THE BARBICAN CITY Barbican 2&3, Beech Street, EC2Y 8AE |Barbican 1, Level 2, Silk Street, EC2Y 8DS

Two brand new screens (2 and 3) separate to the main event off Beech Street, replete with Camera Café and Bar add a new dimension to the huge and varied complex that is the Barbican Centre, containing as it does theatre spaces, Concert Hall and conference capability, bookshop, library and cafes. There’s an amazing wall composed of film photos and images which allows you to scan information about films portrayed on to your mobile phone.

CATERING – Spacious modern café bar on Beech Street complements the other cafes and restaurant in the main complex on Silk Street, with lakeside seating. Sandwiches, daily specials including soup of the day, salads, savoury tart and a hot dish. Everything made on site. Opening hours Mon – Fri: 8am – 10.30pm, Sat & Sun 10am – 10.30pm

SEATING/COMFORT – Very comfortable fitted seats.

TECHNICALS – Cinema 1- 280 seats. 35mm film projection. 2K HD video projection. Beta SP and Digibeta, DVD, All aspect ratios. Microphone. Dolby SR.

DESIGN – The new cinemas have only just opened as a new build. Full disabled access.

TICKETS – online or by phone. Monday Madness- super deals. Also Orange Wednesdays. Membership offers 20% off films and priority booking.

SPECIALS – Framed Film Club for kids, Silent Film and Live Music Series, Wonder on Film, A Grammar of Subversion, Family films, Met Opera Live, Marcel Duchamp dancing, Architecture on Film, Q&A’s. Barbican film enquiries film@barbican.org.uk

ELECTRIC CINEMA – NOTTING HILL, 191 Portobello Road, W11 2ED

FIrst opened in 1910 and one of the first buildings in Britain designed specifically for motion picture showing by Gerald Seymour Valentin in the Edwardian Baroque style. It’s said that the notorious murderer John Christie (1899-1953) worked there as a projectionist. Hands down one of the most comfortable, even hedonistic seating experiences in London, if not the country. Showing mostly indie and avantgarde arthouse fare, The Electric is a sumptuous affair that needs to be experienced at least once. It also houses the upstairs private members’ club ELECTRIC HOUSE.

CATERING – open half an hour prior to screenings, the bar offers snacks, cocktails, wine, beer and champagne.

SEATING/COMFORT – Sixty-five leather armchairs with footstools and side tables offer unparalleled comfort. In addition there are three 2-seater sofas at the rear of the theatre and six double beds in the front row providing a unique cinema experience. Individual cashmere blankets complete the picture.

TECHNICALS – 35mm film projection. Sky HD, DVD, BluRay video projection. DigiBeta, HD-D5, HDCAM-SR, HDCAM, DVCAM, HDDV.

DESIGN – Purpose built in 1911, beautiful inside and out.

TICKETS – Online or by phone, up until an hour before performance starts.

SPECIALS – Kids Club, Electric Scream, Membership discounts.

PHOENIX CINEMA – EAST FINCHLEY, 52 High Road, London N2 9PJ

PHOENIX CINEMA – EAST FINCHLEY, 52 High Road, London N2 9PJ

Built in 1910, the Phoenix is the second oldest continuously-running cinema in Britain and redolent of the Electric in Notting Hill. A truly gorgeous cinema with traditional red velvet seating and the open, vaulted ceiling means no pillars. Unlike modern multi-screens, the best seats are in the middle of the auditorium. Atmospheric and beautiful, it’s run by a trust for the community and has a very active fan-base.

CATERING – The café bar is open from 11am every Monday-Saturday and from 1pm Sundays, serving simple breakfasts and a range of homemade meals and cakes.d a SEATING/COMFORT – Proper old-school red velvet reclined seats.TECHNICALS – 255 seats. 35mm film projection. HD video projection. Beta SP and Digibeta, DVD. All aspect ratios.DESIGN –Full disabled access and four wheelchair spaces.

TICKETS – 0208 444 6789 www.phoenix.co.uk

SPECIALS – NT Live, Ballet from Moscow, Classic films, Q&A’s, Membership benefits.

WATERMANS BRENTFORD, 40 High Street, TW8 0DS

WATERMANS BRENTFORD, 40 High Street, TW8 0DS

Box Office: +44 (0)20 8232 1010

Another component of the Picturehouses Group. A comprehensive Arts and Community Centre, overlooking the River Brent, containing cinema, theatre, meeting rooms, restaurant and ample parking. Makes an effort to be inclusive to Black and Minority ethnic cultures.

CATERING – River Terrace Café bar with wi-fi, comfy sofas with river views, teas, coffees, cakes and pastries, as well as tapas. Outdoor seating. Tandoori restaurant.

SEATING/COMFORT –

TECHNICALS – 239 seats. 35mm film projection. HD video projection. Beta SP and Digibeta, DVD, All aspect ratios.

DESIGN – Purpose built structure, wheelchair accessible.

TICKETS – Friend Concessions, Student and Child concessions. Online booking.

SPECIALS – Discounts for Friends of Watermans, Deals on film and food on Tuesdays. Comprehensive community programs. Parent and Baby screenings, Kids screenings, exhibitions, live events.

RIO CINEMA – DALSTON, HACKNEY

One of the last remaining cinemas over in the Hackney/Dalston area, the Rio stands as a reminder of times past, with the 1930’s façade still intact and a splendid art deco interior. Re-opened in 1999, after substantial refurbishment and new seats, the Rio plays an active role in the community and has taken on the Turkish, Kurdish, Spanish and Gay and Lesbian Film Festivals in recent years.

CATERING – foyer café during normal cinema opening hours. Usual stuff, plus coffee, herbal teas and a licensed bar for beer and wine.

SEATING/COMFORT – 560 seater, very comfortable.

TECHNICALS – 35mm film projection. Sky HD, DVD, BluRay video projection. DigiBeta, HD-D5, HDCAM-SR, HDCAM, DVCAM, HDDV. All aspect ratios. Dolby.

DESIGN – Stylish atmospheric, with the original 1930’s exterior design, but state of the art interior. Three permanent wheelchair spaces available.

SPECIALS Parents & Babies Club, most Tues and Thurs. Saturday Morning Picture Club and Playcentre matinees. Midweek Classic Matinees. Friends of the Rio membership deals also available.

CURZON MAYFAIR | 38 Curzon Street, London, W1. Booking Line: 0330 500 1331

Re-opened in 1966 subsequent to a rebuild, the original 560 seater was converted to two screens in 2002. In the heart of Mayfair, the Curzon Mayfair was voted in the top twenty cinemas in London and has been an arthouse and Indie venue since it opened in the 1930’s. Even now, it still plays host to a dozen or so Premiers annually. Celebrating 75 years in 2009, Mayfair is the heart of Curzon Cinemas with a rich cinematic history and a dedicated audience of film enthusiasts.

CATERING – Licensed bar and screens. Bar has 120 capacity, free wifi. Shop sells DVD and Blu-Ray.

SEATING/COMFORT – Screen One has 311 seats with 2 wheelchair spaces. Newly upholstered with more legroom than many cinemas. Has two Royal Boxes for hire.

Screen Two- 101 seats.

TECHNICALS – 35mm film projection, 2K HD Video projection from HD (Quvis server system) Beta SP and digibeta,DVD, Data, Mini DV. All aspect ratios. Spotlight. Raked stage. Wired microphones and PA. Lectern. Data and mic connection from auditorium or projection box. Full disabled access. Air conditioned

DESIGN – Grade II listed. The bar, foyer and Screen 1 have wheelchair access. An infrared loop system is in both Screen 1 and 2 for the hard of hearing.

SPECIALS – Curzon Q&A’s, DocDays, Met Opera Live, Opera & Ballet, Special Previews, Human Rights Watch FF, Rendezvous with French cinema, Kinoteka Polish FF. Membership.

ROXY – SOUTHWARK | 128-132 Borough High Street, London SE1 1LB

Roxy was created to bring together cutting-edge digital screenings with high quality drinks & food available throughout all screenings. All public screenings are over-18s only.

CATERING –Caters food-wise for around 100. To book, phone 020 7407 4057 or email bookings@roxybarandscreen.com SEATING/COMFORT – 100 seater. TECHNICALS – Panasonic HD projector, a 4m wide cinema screen and a Yamaha 5.1 pro-theatre surround sound system. DESIGN – Modern, urban and fully accessible. SPECIALS – Membership offers discount and priority booking. Also screens live sports events. See website for details. Book your party on a Friday or Saturday night and they’ll give you a bottle of Prosecco too! See here for more info. Phone:- 020 7407 4057Email:- bookings@roxybarandscreen.com

GENESIS -STEPNEY | 93 – 95 Mile End Road

Whitechapel,

London

E1 4UJ

Stands on a site used for entertainment purposes for over 150 years. The first building on the site opened about 1848 as the Eagle public house, a pub cum music hall. This gave way to Lusby’s Summer and Winter Garden which was later renamed Lusby’s Music Hall. Demolished and rebuilt in 1939 and subsequently modernised and split into five screens and a bar area. Great coffee and pastries.

CATERING – Fully licensed bar.

CATERING – Fully licensed bar.

SEATING/COMFORT – Five screens offer from 575 through to 100 seating capacity. Modern, utilitarian design.

TECHNICALS – 35mm film projection. Digital projection. Dolby. Radio microphone.

DESIGN – Art deco exterior but modern inside.

TICKETS – Online or by phone. See below. Call 020 7780 2000.

PHOENIX – OXFORD PICTUREHOUSE | 0871 902 573657 Oxford, Oxfordshire County OX2, UK

Originally built in 1913, In 1970 it was taken over by Star Entertainments Ltd. and converted into Studios One and Two. Following another change of ownership it was renamed the Phoenix Cinema and in 1989 it became the first cinema to be owned and run by the newly formed City Screen Limited. A final addition of the roof-top bar in the 1990s brought the cinema to its current configuration.

CATERING – Fully licensed bar.

SEATING/COMFORT – Two screens, 198 and 98 seaters.

TECHNICALS – 35mm film projection. Digital projection. All aspect ratios. Dolby.

DESIGN – Both auditoria are accessible to customers with limited mobility including wheelchair users. Please note wheelchair spaces are limited. The first floor bar is Not accessible. Advisable to call in advance.

TICKETS – Online or by phone telephone lines are open from 9.30am – 8.30pm, seven days a week. Please call 0871 902 5736 (calls cost 10p a minute from a BT landline). Booking fee applies.

WILTON’S – TOWER HAMLETS

WILTON’S – TOWER HAMLETS

Wilton’s is the world’s oldest surviving Grand Music Hall and London’s best kept secret. This stunning and atmospheric building houses a programme of imaginative, diverse and distinct entertainment including theatre, music, comedy, cinema and cabaret. See website for what’s on.

CATERING – The Mahogany bar- fully licensed bar and venue. The Green Room Bar. Lunchtime Kitchen.

SEATING/COMFORT – variable, freestanding chairs, rather than upholstered seats.

TECHNICALS – 35mm film projection. Digital projection. Dolby.

DESIGN – Unique, beautiful original music hall, must be visited at least once to experience.

TICKETS – Online or phone, Enquiries & Box Office 020 7702 2789 Monday – Friday (excluding bank holidays) 12pm – 11pm

Saturday 5pm – 11pm

Serving cocktails upstairs Tuesday – Saturday 6pm – 11pm

PRINCE CHARLES – West End | 020 74943654 | 7 Leicester Place

Right in the heart of the West End in Leicester Place, a firm favourite with the arthouse indie crowd, often serving up arthouse films once they have completed a release, so a good chance to catch up on something you missed, if you keep an eye on what’s coming up.

CATERING – Fully licensed and comprehensive bar.

SEATING/COMFORT – Two screens- 285 and 104.

TECHNICALS – 35mm film projection. digital projection. All aspect ratios. Dolby.

TICKETS – Online or by phone, https://www.jack-roe.co.uk/TaposWebSales/Main/prilon/start

SPECIALS – Marathons (eg Alien), retrospectives and trilogies (e.g. Die Hard, Terminator, Singalongs (e.g. Sound Of Music, Rocky Horror).

www.princecharlescinema.com

THE REX – BERKHAMSTED |

THE REX – BERKHAMSTED |

High St (Three Close Lane)

Berkhamstead

HP4 2HD

The Rex has one huge screen set in a glorious 1938 art-deco proscenium with the sharpest film projection and clearest non-booming sound anywhere in the world. Serves up mainstream as well as arthouse fare.

CATERING – Selection of food and drink, with bars upstairs and downstairs open throughout the film.

SEATING/COMFORT – Throughout, its seating is big and soft. It has been called luxurious. It is better. It is civilized. It reminds us of what we have long stopped expecting from public buildings.

TECHNICALS – 35mm film projection. Digital projection. All aspect ratios. Dolby.

DESIGN – Disabled Access is from the High Street. There is a gate to the right of the white apartment block (The Gatsby stands far left). The gate is opened 45 minutes before the start time of the film, but if you find it locked please call our admin line: 01442 877999.

THE HORSE HOSPITAL – BLOOMSBURY | (0)20 7833 3644

Built in 1797 as stabling for cabby’s sick horses, The Horse Hospital is a unique Grade II listed venue providing space for avantegarde and underground media since 1993.

Situated on the lower ground floor, the stable room offers a convivial and unusual environment with its horse ramp entrance, tethering rings, cast iron pillars and amazing cobbled floor. Clients have included the BFI, Birkbeck, Central St Martins, Fashion in Film Festival, Slingshot Films, The Italian Film Society amongst others.

CATERING – Organised by function

SEATING/COMFORT – freestanding chairs.

TECHNICALS – video/digital projection.

DESIGN – Built in 1797 as stabling for cabby’s sick horses, The Horse Hospital is now a unique Grade II listed arts venue situated in an unspoilt mews in the heart of Bloomsbury,

THE OLD RED LION THEATRE CINEMA CLUB – Islington’s local indie cinema in the heart of the local shopping thoroughfare.

Seats: The seats are long wooden benches with padded tops and backs.

Technical capabilities: We are capable of showing Blu-ray and regular DVD content. Our screen is big for the space so you’ve a great view from wherever you’re sitting.

Catering: We aim to be selling Ice Cream, Crisps and Retro sweets. We’re also a pub so downstairs in the bar there’s all the beer you can drink!

location: We’re located at 418 St John Street EC1V 4NJ, very close to Angel Tube station. The building is called the Old Red Lion Theatre Pub

specials: All tickets are £6.50 and there is no booking fee through our sales host.

JW3 CULTURAL, ARTS AND COMMUNITY CENTRE, FINCHLEY ROAD, LONDON NW3

JW3’s comfy seats, intimate feel as a 60-seater and wonderful café, bar and restaurant – ZEST opened to rave reviews in September 2013. The original programming is also a big selling point of the cinema.

JW3’s comfy seats, intimate feel as a 60-seater and wonderful café, bar and restaurant – ZEST opened to rave reviews in September 2013. The original programming is also a big selling point of the cinema.

Partnered with UK Jewish Film to show 6 screenings of Jewish and Israeli films from all round the world, JW3 also shows new releases and run a number of film clubs on Monday evenings including: Comedy Film Club in partnership with LOCO (London Comedy Film Festival), Artists’ Film Salon for filmmakers and artists working with artists’ moving image and the Foodies Film Club with special edible cinema experiences.

For listings visit the JW3 website

THE ART HOUSE CROUCH END, 159A TOTTENHAM LANE, LONDON N8 9BT

The former Salvation Army Hall (Music Palace) in Crouch End, North London is being transformed into a dynamic new cultural venue called ArtHouse. Crouch-Enders George Georgiou, Sam Neophytou and Tom Barrie are on a mission to put Crouch End firmly on the cultural map.

The cinema will have two state of the art screens totaling approx 190 seats. Run in association with Curzon, we will show a mix of mainstream, foreign and ArtHouse films, including live streams of classic theatre, opera and ballet from world renowned companies as well as regular director Q&As, documentary events and special events.

SAFFRON SCREEN, Audley End Road, Saffron Walden, Essex CB11 4UH

Saffron Screen is an independent not for profit cinema showing mainstream and art house fare and streaming international cultural events. with a view to entertaining, educating and creating a welcoming experience for the local community. SAFFRON also provides full accessibility for the physically and visually impaired. For the full Programme click the link.

CURZON VICTORIA

A welcome addition to this poorly served area of London, cinema-wise. The CURZON VICTORIA opened at the end of 2014. Indulge yourselves with carefully selected wines, local beers and spirits in their brand new luxury lounge bars before enjoying five state-of-the-art screens with Sony 4K projection and 3D.

CLOSE-UP FILM CENTRE

This Shoreditch-based cinema club is open daily from 12-10pm so check it out.

IF YOU WOULD LIKE YOUR CINEMA SCREEN TO BE FEATURED IN THIS GUIDE, PLEASE CONTACT US @filmuforia OR ON THE CONTACT SHEET ON THE HOME PAGE

Dir.: Georgui Balabanov; Documentary with Christo, Jeanne-Claude, Anani Yavashev; Bulgaria 1996, 72 min.

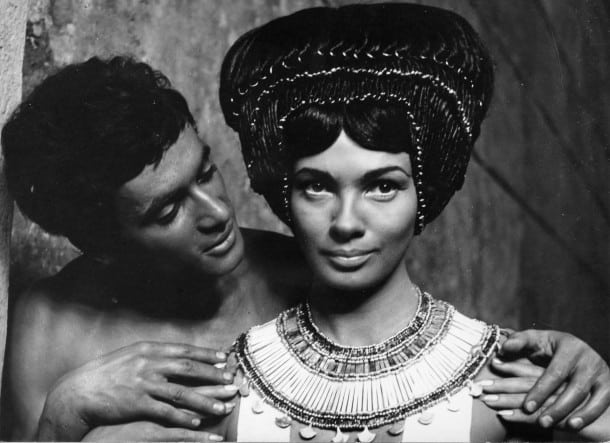

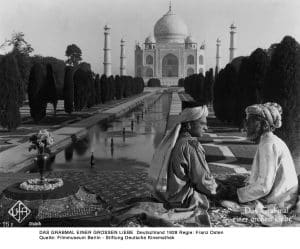

Dir.: Georgui Balabanov; Documentary with Christo, Jeanne-Claude, Anani Yavashev; Bulgaria 1996, 72 min. Shiraz is a fictitious character, the son of a local potter who rescues a baby girl from the wreckage of a caravan laden with treasures, ambushed while transporting her mother, a princess. Shiraz is unaware of Selima’s royal blood and he falls madly in love with her as the two grow up in their simple surroundings, until she is kidnapped and sold to Prince Khurram of Agra (a sultry Charu Roy). Shiraz then risks his life to be near her in Agra as the Prince also falls for her charms.

Shiraz is a fictitious character, the son of a local potter who rescues a baby girl from the wreckage of a caravan laden with treasures, ambushed while transporting her mother, a princess. Shiraz is unaware of Selima’s royal blood and he falls madly in love with her as the two grow up in their simple surroundings, until she is kidnapped and sold to Prince Khurram of Agra (a sultry Charu Roy). Shiraz then risks his life to be near her in Agra as the Prince also falls for her charms. Apart from being gorgeously sensual (there is a highly avantgarde kissing scene ) and gripping throughout, SHIRAZ is also an important film in that it united the expertise of three countries: Rai’s Great Eastern Indian Corporation; UK’s British Instructional Films (who also produced Anthony Asquith’s Shooting Stars and Underground in 1928) and the German Emelka Film company. Contemporary sources tell of “a serious attempt to bring India to the screen”. Attention to detail was paramount with an historical expert overseeing the sumptuous costumes, furnishings and priceless jewels that sparkle within the Fort of Agra and its palatial surroundings. Glowing in silky black and white SHIRAZ is one of the truly magical films in recent memory. MT

Apart from being gorgeously sensual (there is a highly avantgarde kissing scene ) and gripping throughout, SHIRAZ is also an important film in that it united the expertise of three countries: Rai’s Great Eastern Indian Corporation; UK’s British Instructional Films (who also produced Anthony Asquith’s Shooting Stars and Underground in 1928) and the German Emelka Film company. Contemporary sources tell of “a serious attempt to bring India to the screen”. Attention to detail was paramount with an historical expert overseeing the sumptuous costumes, furnishings and priceless jewels that sparkle within the Fort of Agra and its palatial surroundings. Glowing in silky black and white SHIRAZ is one of the truly magical films in recent memory. MT Dresden 1918, Robert Siodmak left his upper-middle class, orthodox Jewish home in this epicentre of European modern art, to join a theatre touring company. He was 18, and this was the first of many radical changes that would see him becoming a pioneer of film noir, and directing 56 feature films fraught with (anti)heroes who are morose, malevolent, violent and generally downbeat (spoilers).

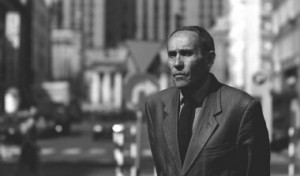

Dresden 1918, Robert Siodmak left his upper-middle class, orthodox Jewish home in this epicentre of European modern art, to join a theatre touring company. He was 18, and this was the first of many radical changes that would see him becoming a pioneer of film noir, and directing 56 feature films fraught with (anti)heroes who are morose, malevolent, violent and generally downbeat (spoilers).

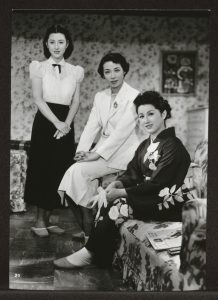

The Flavour of Green Tea Over Rice tells the story of a marriage slowly imploding as Japan shifts into the modern world from its pre war traditions.

The Flavour of Green Tea Over Rice tells the story of a marriage slowly imploding as Japan shifts into the modern world from its pre war traditions.

Elliptical in nature, in the same way as

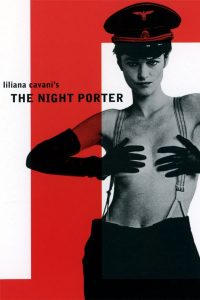

Elliptical in nature, in the same way as  THE NIGHT PORTER (Il portiere di notte) Dir: Liliana Cavani | Cast: Dirk Bogarde, Charlotte Rampling, Philippe Leroy | 118 mins

THE NIGHT PORTER (Il portiere di notte) Dir: Liliana Cavani | Cast: Dirk Bogarde, Charlotte Rampling, Philippe Leroy | 118 mins

AN ELEPHANT SITTING STILL (2019)

AN ELEPHANT SITTING STILL (2019) SON OF SAUL (2015) Laszlo Nemez

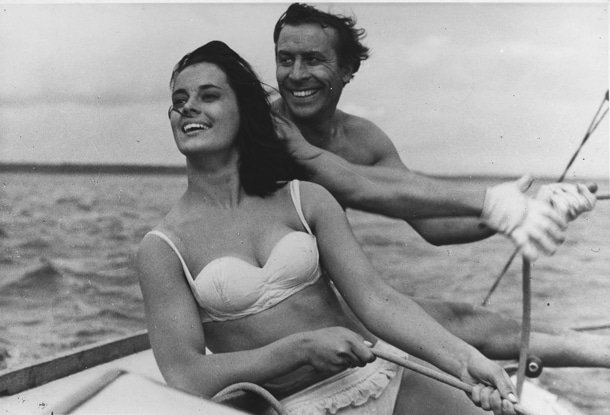

SON OF SAUL (2015) Laszlo Nemez Karina went on to star in seven of his films, the first was Le Petit Soldat that same year. She won Best Actress at the Berlin Film Festival in 1961 for Une Femme est une Femme. While marriage to Godard was stormy to say the least – he neglected her emotionally – “he was the sort of man who would go for a packet of cigarettes and return three weeks later” – their artistic relationship blossomed with a string of New Wave hits: Vivre sa Vie (1962); Bande a Part (1964); Pierrot Le Fou (1965); Alphaville (1965) and Made in USA (1966). When Godard cast her in his episode ‘Anticipation’ for The Oldest Profession (1966), they were already divorced and not on speaking terms. But Karina stayed loyal to Godard and a few years ago at the BFI she talked about him in glowing terms.

Karina went on to star in seven of his films, the first was Le Petit Soldat that same year. She won Best Actress at the Berlin Film Festival in 1961 for Une Femme est une Femme. While marriage to Godard was stormy to say the least – he neglected her emotionally – “he was the sort of man who would go for a packet of cigarettes and return three weeks later” – their artistic relationship blossomed with a string of New Wave hits: Vivre sa Vie (1962); Bande a Part (1964); Pierrot Le Fou (1965); Alphaville (1965) and Made in USA (1966). When Godard cast her in his episode ‘Anticipation’ for The Oldest Profession (1966), they were already divorced and not on speaking terms. But Karina stayed loyal to Godard and a few years ago at the BFI she talked about him in glowing terms. “Stanislavsky said there are no small parts, only small actors”. Harvey Keitel proved this when he took the ‘unadvertised lead’ with a few lines and made it into a memorable one as ‘a pimp standing in the doorway’ in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. Scorsese had wanted him to be the campaign worker, but he took his cue from years of living in Hell’s Kitchen amongst the drug traffickers and sex workers of the area. Spending two weeks learning to be the pimp after having first playing the girl during rehearsals the words of the real life pimp still send chills down his body: “Remember. You love her”

“Stanislavsky said there are no small parts, only small actors”. Harvey Keitel proved this when he took the ‘unadvertised lead’ with a few lines and made it into a memorable one as ‘a pimp standing in the doorway’ in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. Scorsese had wanted him to be the campaign worker, but he took his cue from years of living in Hell’s Kitchen amongst the drug traffickers and sex workers of the area. Spending two weeks learning to be the pimp after having first playing the girl during rehearsals the words of the real life pimp still send chills down his body: “Remember. You love her”

MARIE-LOUISE IRIBE Parisian actress and filmmaker, Marie Louise Iribe (1894-1934) had a short but dazzling career and is best known for her 1928 debut Hara-Kiri (co-directed with Henri Debain). Her follow-up Le Roi de Aulnes (1931) is based on a poem by Goethe. This enchanting filigree fairy tale has the same magical touch and look as Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête which followed 15 years later and during wartime. The simple but moving storyline sees a man riding through hill and dale to carry his injured son home. As he slips in an out of consciousness the boy imagines death as a mythical king surrounded by wood nymphs. Emile Pierre delicately overlays the forest journey with ethereal images of the king in iridescent armour, transformed from a humble toad realised by DoP Emilie Pierre’s ethereal double exposures. Max D’Ollone’s atmospheric score brings the magic to life.

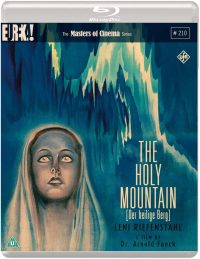

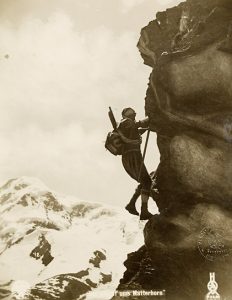

MARIE-LOUISE IRIBE Parisian actress and filmmaker, Marie Louise Iribe (1894-1934) had a short but dazzling career and is best known for her 1928 debut Hara-Kiri (co-directed with Henri Debain). Her follow-up Le Roi de Aulnes (1931) is based on a poem by Goethe. This enchanting filigree fairy tale has the same magical touch and look as Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête which followed 15 years later and during wartime. The simple but moving storyline sees a man riding through hill and dale to carry his injured son home. As he slips in an out of consciousness the boy imagines death as a mythical king surrounded by wood nymphs. Emile Pierre delicately overlays the forest journey with ethereal images of the king in iridescent armour, transformed from a humble toad realised by DoP Emilie Pierre’s ethereal double exposures. Max D’Ollone’s atmospheric score brings the magic to life. In spite of a new revisionist film history, which tries to exonerate the BERGFILM sub-genre from its close connection with Fascist ideology, the filmmakers of the Weimar years and their chosen subjects were close allies of German Fascism – and Leni Riefenstahl was arguably its leading film propagandist. Attempting to link the Bergfilm with what Kracauer called “Streetfilms”, is aesthetically and content wise a dishonest bid to rewrite (film)history. Streetfilms were set in big cities where the male protagonist falls for a sexually alluring woman from a lower social class, only to be roped back to roost in his middle-class milieu by figures of authority. The Bergfilm might feature alluring women (Riefenstahl certainly qualified), but the narrative comes to very different solutions, and this is amply demonstrated in Luis Trenker’s The Prodigal Son (Der verlorene Sohn, 1932), which sees the hero falling for an alluring ‘foreign’ woman, who embroils his in the traumas of big city life before he escapes triumphantly back to his home in the mountains to become an upright citizen and family man. You don’t have to take my word for it – Dr. Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary during a visit to the mountains: “That was my yearning; for all the divine solitude and calm of the mountains, for white, virginal (sic!) snow, I was weary of the big city. I am at home again in the mountains. I spent many hours in their white unspoiltness and find myself again”.

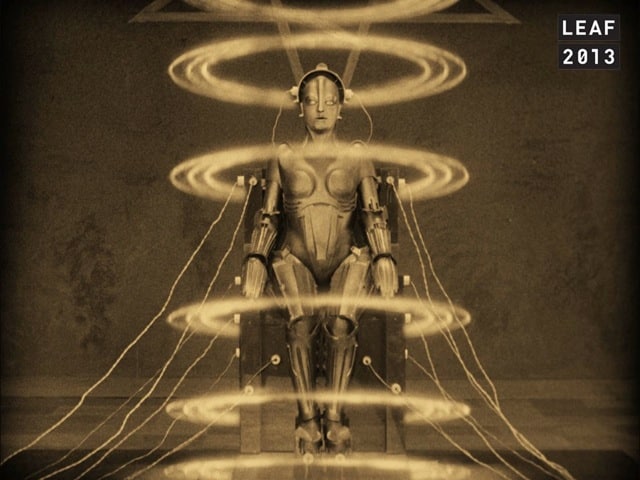

In spite of a new revisionist film history, which tries to exonerate the BERGFILM sub-genre from its close connection with Fascist ideology, the filmmakers of the Weimar years and their chosen subjects were close allies of German Fascism – and Leni Riefenstahl was arguably its leading film propagandist. Attempting to link the Bergfilm with what Kracauer called “Streetfilms”, is aesthetically and content wise a dishonest bid to rewrite (film)history. Streetfilms were set in big cities where the male protagonist falls for a sexually alluring woman from a lower social class, only to be roped back to roost in his middle-class milieu by figures of authority. The Bergfilm might feature alluring women (Riefenstahl certainly qualified), but the narrative comes to very different solutions, and this is amply demonstrated in Luis Trenker’s The Prodigal Son (Der verlorene Sohn, 1932), which sees the hero falling for an alluring ‘foreign’ woman, who embroils his in the traumas of big city life before he escapes triumphantly back to his home in the mountains to become an upright citizen and family man. You don’t have to take my word for it – Dr. Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary during a visit to the mountains: “That was my yearning; for all the divine solitude and calm of the mountains, for white, virginal (sic!) snow, I was weary of the big city. I am at home again in the mountains. I spent many hours in their white unspoiltness and find myself again”. There is a strong link between Anti-Urbanism, unspoilt elements of nature, destiny (in German ‘Vorsehung’, Hitler’s favourite phrase) and a surrender to irrational values: exactly the cinema which Kracauer describes in his ground breaking text. Yes, there was modern technology: telescopes and microscopes – and airplanes. But one look at Riefenstahl’s films of the Nazi Party get togethers in Nuremberg (Sieg des Glaubens, Triumph des Willens) shows the underlying irrationality: after we have seen the city full of “believers”, Hitler comes down from the sky in a plane. A demi-God, winged like in Greek mythology, he flies into the world to make it sane (heil) again. In German the phrase of ‘heile Welt’ is still used to define a system without any contradiction, perfect by definition. In comparing the Nazi regime with eternal nature, all clean and sane, its opponents are immediately categorised as unclean. In the case of Jews, they were vermin, to be eradicated.

There is a strong link between Anti-Urbanism, unspoilt elements of nature, destiny (in German ‘Vorsehung’, Hitler’s favourite phrase) and a surrender to irrational values: exactly the cinema which Kracauer describes in his ground breaking text. Yes, there was modern technology: telescopes and microscopes – and airplanes. But one look at Riefenstahl’s films of the Nazi Party get togethers in Nuremberg (Sieg des Glaubens, Triumph des Willens) shows the underlying irrationality: after we have seen the city full of “believers”, Hitler comes down from the sky in a plane. A demi-God, winged like in Greek mythology, he flies into the world to make it sane (heil) again. In German the phrase of ‘heile Welt’ is still used to define a system without any contradiction, perfect by definition. In comparing the Nazi regime with eternal nature, all clean and sane, its opponents are immediately categorised as unclean. In the case of Jews, they were vermin, to be eradicated. Das Blaue Licht won an award in Venice and convinced Hitler that Riefenstahl should direct the Nuremberg rally documentaries. A post war critic in the ‘Cine-Club de Toulouse’ wrote in 1949, picking up on the Siegfried theme: “It is the always eternal topic of Siegfried, as the young hero. Because always the young men are ready to sacrifice their lives, and only have contempt for everything, which does not omply with their ideas. This is a feature seen entirely from the viewpoint of Nazi ideology. We find the same sort of youth enthusiasm seen in Riefenstahl’s Nuremberg documentaries. Young people joined in with the hope that the regime would reward them because of their racial purity”.

Das Blaue Licht won an award in Venice and convinced Hitler that Riefenstahl should direct the Nuremberg rally documentaries. A post war critic in the ‘Cine-Club de Toulouse’ wrote in 1949, picking up on the Siegfried theme: “It is the always eternal topic of Siegfried, as the young hero. Because always the young men are ready to sacrifice their lives, and only have contempt for everything, which does not omply with their ideas. This is a feature seen entirely from the viewpoint of Nazi ideology. We find the same sort of youth enthusiasm seen in Riefenstahl’s Nuremberg documentaries. Young people joined in with the hope that the regime would reward them because of their racial purity”.

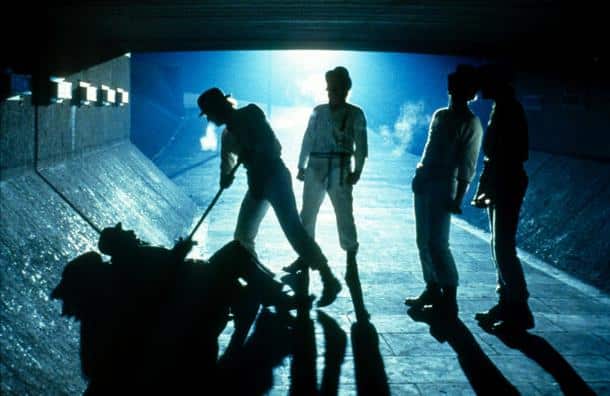

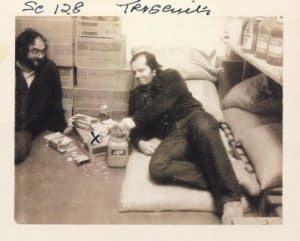

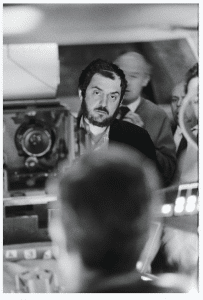

Stanley Kubrick, one of the greatest film makers of the 20th century, spent most of his later life working in England where he raised a family in the Hertfordshire town of Childwickbury, between St Albans and Harpenden, 35 minutes drive North of London. It was in the Norfolk Broads and Beckton, in the East End that he created the Vietnam scenes for Full Metal Jacket (1987), an orbiting space station for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Dr Strangelove’s war room (1964).

Stanley Kubrick, one of the greatest film makers of the 20th century, spent most of his later life working in England where he raised a family in the Hertfordshire town of Childwickbury, between St Albans and Harpenden, 35 minutes drive North of London. It was in the Norfolk Broads and Beckton, in the East End that he created the Vietnam scenes for Full Metal Jacket (1987), an orbiting space station for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Dr Strangelove’s war room (1964). Stanley Kubrick was most inventive in his introduction of revolutionary devices to his filmmaking, such as the camera lens designed for NASA to shoot by candlelight. His fascination with all aspects of design and architecture influenced every stage of all his films. He worked with many key designers of his generation, from Hardy Amies to Saul Bass, Eliot Noyes and Ken Adam.

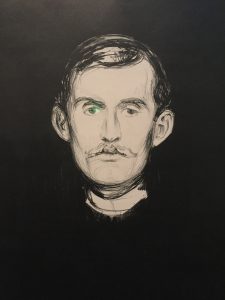

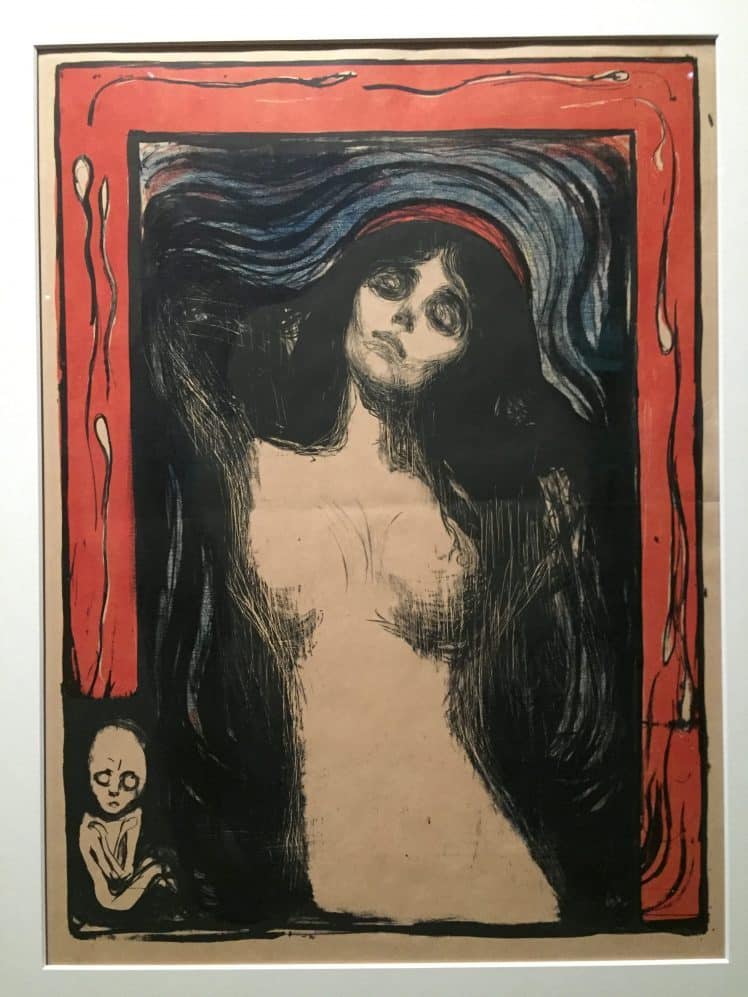

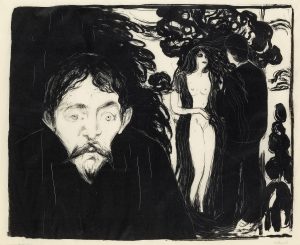

Stanley Kubrick was most inventive in his introduction of revolutionary devices to his filmmaking, such as the camera lens designed for NASA to shoot by candlelight. His fascination with all aspects of design and architecture influenced every stage of all his films. He worked with many key designers of his generation, from Hardy Amies to Saul Bass, Eliot Noyes and Ken Adam. Edvard Munch (1863-1944) was a famous pioneer of modern art, best known for his iconic image of The Scream. His idiosyncratic expression of raw human emotion reflects many of the anxieties and hotly debated issues of his times, yet his art still still resonates today.

Edvard Munch (1863-1944) was a famous pioneer of modern art, best known for his iconic image of The Scream. His idiosyncratic expression of raw human emotion reflects many of the anxieties and hotly debated issues of his times, yet his art still still resonates today.

During his life Munch spent much time in Paris and Berlin where in 1892, he was invited to exhibit his paintings in the recently formed German Empire. Berlin was Europe’s industrial boom city, ruled over the ambitious Kaiser Bill (Wilhelm II). Grand avenues gave the impression of military order but bohemian undercurrents ran just below the surface, alongside Europe’s strongest workers’ movement. His exhibition horrified the traditional art world, but was much admired by the Avantgarde with the scandal helping him to launch his international career.

During his life Munch spent much time in Paris and Berlin where in 1892, he was invited to exhibit his paintings in the recently formed German Empire. Berlin was Europe’s industrial boom city, ruled over the ambitious Kaiser Bill (Wilhelm II). Grand avenues gave the impression of military order but bohemian undercurrents ran just below the surface, alongside Europe’s strongest workers’ movement. His exhibition horrified the traditional art world, but was much admired by the Avantgarde with the scandal helping him to launch his international career.

Turkish cinema is known for its captivating widescreen dramas that reflect the cultural diversity and magnificent scenery of a vibrant nation that stretches from Europe to Asia.

Turkish cinema is known for its captivating widescreen dramas that reflect the cultural diversity and magnificent scenery of a vibrant nation that stretches from Europe to Asia. The Golden Tulip winner 2017 YELLOW HEAT (Sari Sicak) sees an immigrant family desperate to survive in their traditional farm amid encroaching industrialisation. The multi-award winning drama YOZGAT BLUES (2013), set in small town Anatolia, is one to watch for its outstanding performances and smouldering cinematography. Banu Sivaci’s THE PIGEON (main image) won best director at Sofia Film Festival 2018 and is another impressive arthouse tale of a boy finding peace with the animal kingdom, away from the dystopian world in small-town Adana, Southern Turkey. And finally MURTAZA another beautifully crafted and resonant parable about the importance of traditional values in the mountains of Malatya.

The Golden Tulip winner 2017 YELLOW HEAT (Sari Sicak) sees an immigrant family desperate to survive in their traditional farm amid encroaching industrialisation. The multi-award winning drama YOZGAT BLUES (2013), set in small town Anatolia, is one to watch for its outstanding performances and smouldering cinematography. Banu Sivaci’s THE PIGEON (main image) won best director at Sofia Film Festival 2018 and is another impressive arthouse tale of a boy finding peace with the animal kingdom, away from the dystopian world in small-town Adana, Southern Turkey. And finally MURTAZA another beautifully crafted and resonant parable about the importance of traditional values in the mountains of Malatya. Other features and shorts reflect the usual Turkish themes of town versus country, tradition versus the modern world, and the role of women in enlightened society. Another highlight will be Ahmet Boyacioglu’s latest film THE SMELL OF MONEY a tense and startling exposé of financial corruption in contemporary Turkey. And last but not least, a panel of industry professionals will debate the future of the big screen At the Flicks of Netflix? at the Regent Street Cinema on 26th April.

Other features and shorts reflect the usual Turkish themes of town versus country, tradition versus the modern world, and the role of women in enlightened society. Another highlight will be Ahmet Boyacioglu’s latest film THE SMELL OF MONEY a tense and startling exposé of financial corruption in contemporary Turkey. And last but not least, a panel of industry professionals will debate the future of the big screen At the Flicks of Netflix? at the Regent Street Cinema on 26th April. The festival will open at the Barbican on 14 March with Hans Pool’s Bellingcat – Truth in a Post-Truth World, which follows the revolutionary rise of the “citizen investigative journalist” collective known as Bellingcat, dedicated to redefining breaking news by exploring the promise of open source investigation.

The festival will open at the Barbican on 14 March with Hans Pool’s Bellingcat – Truth in a Post-Truth World, which follows the revolutionary rise of the “citizen investigative journalist” collective known as Bellingcat, dedicated to redefining breaking news by exploring the promise of open source investigation.

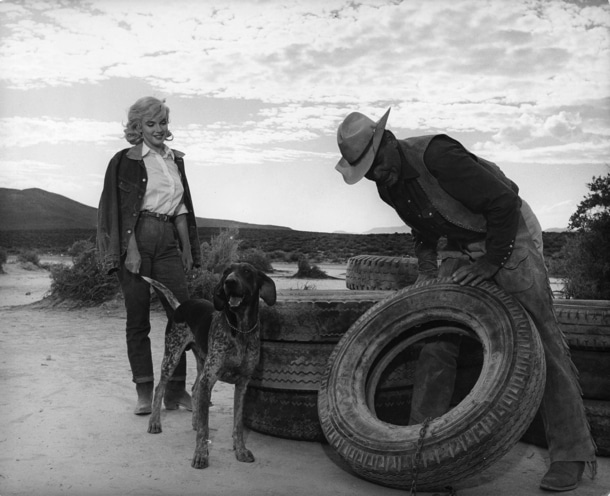

Diva, grande dame and femme fatale, Stanwyck adapted to any genre, be it comedy, melodrama or thriller. Her natural wit and raw emotion was particularly resonant in her Westerns, where she played resourceful, confident women holding their own in a male-dominated world. The BFI are screening 3 examples in March. Her first western Annie Oakley (George Stevens, 1935) was based on the life of ‘Little Miss Sureshot,’ one of the most famous sharpshooters in American history; Stanwyck oozes confidence in her portrayal of the determined and spirited protagonist. Cecil B. DeMille brought a characteristically epic sense of scale to the western with Union Pacific (1939), about the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad. Mixed in with the historical elements is a love triangle between a troubleshooter, a gambler, and a train engineer’s daughter played by Stanwyck. The director was mesmerised by her performance, and she became one of his favourite stars. In Forty Guns (Samuel Fuller, 1957), a late-career highlight for Stanwyck, she portrays a wealthy landowner exerting influence over an Arizonian township by commanding a staff of 40 men. Beautifully shot and packed with psychosexual subtext and directed with bravura, Samuel Fuller’s western influenced a generation of filmmakers, including Godard.

Diva, grande dame and femme fatale, Stanwyck adapted to any genre, be it comedy, melodrama or thriller. Her natural wit and raw emotion was particularly resonant in her Westerns, where she played resourceful, confident women holding their own in a male-dominated world. The BFI are screening 3 examples in March. Her first western Annie Oakley (George Stevens, 1935) was based on the life of ‘Little Miss Sureshot,’ one of the most famous sharpshooters in American history; Stanwyck oozes confidence in her portrayal of the determined and spirited protagonist. Cecil B. DeMille brought a characteristically epic sense of scale to the western with Union Pacific (1939), about the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad. Mixed in with the historical elements is a love triangle between a troubleshooter, a gambler, and a train engineer’s daughter played by Stanwyck. The director was mesmerised by her performance, and she became one of his favourite stars. In Forty Guns (Samuel Fuller, 1957), a late-career highlight for Stanwyck, she portrays a wealthy landowner exerting influence over an Arizonian township by commanding a staff of 40 men. Beautifully shot and packed with psychosexual subtext and directed with bravura, Samuel Fuller’s western influenced a generation of filmmakers, including Godard.

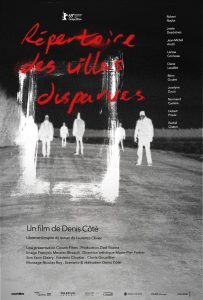

Dir/Wri: Denis Côté | Fantasy Drama | Canada, 97′

Dir/Wri: Denis Côté | Fantasy Drama | Canada, 97′ Dir.: Edgar Pera; Cast: Dominique Pinon, Alba Baptista, Pauko Pires, Ney Matograsso, Albano Jeronimo; Brazil/Portugal 2018, 90 min.

Dir.: Edgar Pera; Cast: Dominique Pinon, Alba Baptista, Pauko Pires, Ney Matograsso, Albano Jeronimo; Brazil/Portugal 2018, 90 min.

Dir.: Volker Schlöndorff, Margaretha von Trotta; Cast: Angela Winkler, Mario Adorf, Jürgen Prochnow, Dieter Laser, Heinz Bennett, Hannelore Hoger, Rolf Becker; Federal Republic of Germany 1975, 106’.

Dir.: Volker Schlöndorff, Margaretha von Trotta; Cast: Angela Winkler, Mario Adorf, Jürgen Prochnow, Dieter Laser, Heinz Bennett, Hannelore Hoger, Rolf Becker; Federal Republic of Germany 1975, 106’.

An intimate child-friendly venue (ever been locked in with a two-year old tantrum) that offers all the latest arthouse films just around the corner for Crouch End and Stroud Green dwellers. Membership scheme available.

An intimate child-friendly venue (ever been locked in with a two-year old tantrum) that offers all the latest arthouse films just around the corner for Crouch End and Stroud Green dwellers. Membership scheme available.

Dir: Anatoly Vasilyev | Doc | Russia | 167′

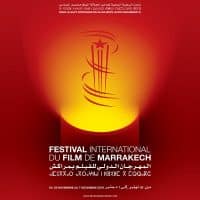

Dir: Anatoly Vasilyev | Doc | Russia | 167′ Marrakech International Film Festival (FIFM) is back this year under the artistic control of its newly appointed director Christoph Terhechte. It will run from 30 November until 8 December 2018.

Marrakech International Film Festival (FIFM) is back this year under the artistic control of its newly appointed director Christoph Terhechte. It will run from 30 November until 8 December 2018. This year’s 17th Edition will also honour Robert De Niro, Agnès Varda and Robin Wright along with Moroccan filmmaker Jillali Ferhati. The festival president is James Gray. International stars in the shape of Martin Scorsese, Guillermo del Toro, Cristian Mungiu, and Yousry Nasrallah will also be gracing the Moroccan city and Medina. Along with Cannes luminary Thierry Fremaux.

This year’s 17th Edition will also honour Robert De Niro, Agnès Varda and Robin Wright along with Moroccan filmmaker Jillali Ferhati. The festival president is James Gray. International stars in the shape of Martin Scorsese, Guillermo del Toro, Cristian Mungiu, and Yousry Nasrallah will also be gracing the Moroccan city and Medina. Along with Cannes luminary Thierry Fremaux.

US director James Gray will head the International Competition jury which includes actress Dakota Johnson (50 shades of Grey, Suspiria), Indian actress Ileana D’Cruz (Barfi!), Lebanese filmmaker and visual artist Joana Hadjithomas (I Want to See), British director Lynne Ramsay (We Need To Talk about Kevin, A Beautiful Day), Moroccan director Tala Hadid (House in the Fields), French director Laurent Cantet (The Class– Palme d’Or 2008), German Actor Daniel Brühl and Mexican director Michel Franco (April’s Daughter).

US director James Gray will head the International Competition jury which includes actress Dakota Johnson (50 shades of Grey, Suspiria), Indian actress Ileana D’Cruz (Barfi!), Lebanese filmmaker and visual artist Joana Hadjithomas (I Want to See), British director Lynne Ramsay (We Need To Talk about Kevin, A Beautiful Day), Moroccan director Tala Hadid (House in the Fields), French director Laurent Cantet (The Class– Palme d’Or 2008), German Actor Daniel Brühl and Mexican director Michel Franco (April’s Daughter).

Russian Film Week is back for the third year running. From 25 November to 2 December the event will take place in London at BFI Southbank, Regent Street Cinema, Curzon Mayfair and Empire Leicester Square before heading to Edinburgh, Cambridge and Oxford.

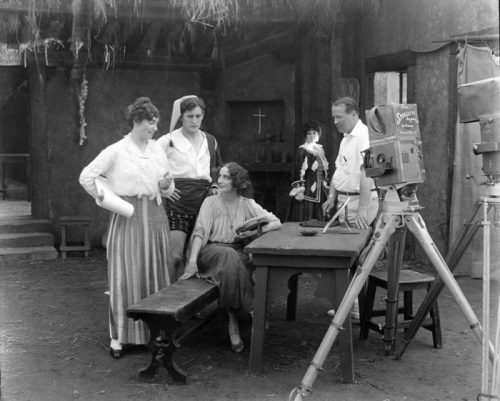

Russian Film Week is back for the third year running. From 25 November to 2 December the event will take place in London at BFI Southbank, Regent Street Cinema, Curzon Mayfair and Empire Leicester Square before heading to Edinburgh, Cambridge and Oxford. Mabel Normand (1892-1930) had a short but eventful life: she was a pioneer of Silent Movies as a star actress (in 220) and director (in 10) between 1910 and 1927. Working alongside Charlie Chaplin, she ended up saving his career at Mack Sennetts’ Keystone – the producer wanted to sack him. Normand also developed Chaplin’s ‘tramp’ screen personality. But she was, more or less, accidentally involved in the murder of William Desmond Taylor and the shooting of Courtland S. Dines, as well as being a friend (and co-star) of ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle, whose life was a series of scandals. Normand suffered for a long time from TB, interrupting her career and leading to her early death at the age of 37.

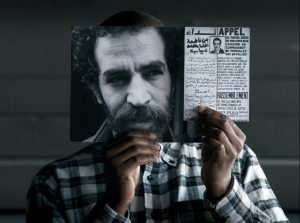

Mabel Normand (1892-1930) had a short but eventful life: she was a pioneer of Silent Movies as a star actress (in 220) and director (in 10) between 1910 and 1927. Working alongside Charlie Chaplin, she ended up saving his career at Mack Sennetts’ Keystone – the producer wanted to sack him. Normand also developed Chaplin’s ‘tramp’ screen personality. But she was, more or less, accidentally involved in the murder of William Desmond Taylor and the shooting of Courtland S. Dines, as well as being a friend (and co-star) of ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle, whose life was a series of scandals. Normand suffered for a long time from TB, interrupting her career and leading to her early death at the age of 37. In Twenty-Two Hours, Bouchra Khalili (left) considers how celebrated French writer Jean Genet was invited by the Black Panther Party to secretly visit them in in the U.S in 1970. The film features Doug Miranda, a former prominent member of the Black Panther Party. Echoing

In Twenty-Two Hours, Bouchra Khalili (left) considers how celebrated French writer Jean Genet was invited by the Black Panther Party to secretly visit them in in the U.S in 1970. The film features Doug Miranda, a former prominent member of the Black Panther Party. Echoing

Moroccan-French artist Bouchra Khalili works with film, video and mixed media. Her focus is on ethnic and political minorities examining the complex relationship between the individual and the community. She is also a Professor of Contemporary Art at The Oslo National Art Academy and a founding member of La Cinematheque de Tanger, an artist-run non-profit organisation based in Tangiers, Morocco. She was the recipient of the Radcliffe Institute Fellowship from Harvard University (2017-2018). Her latest film installation is Twenty-Two Hours (2018).

Moroccan-French artist Bouchra Khalili works with film, video and mixed media. Her focus is on ethnic and political minorities examining the complex relationship between the individual and the community. She is also a Professor of Contemporary Art at The Oslo National Art Academy and a founding member of La Cinematheque de Tanger, an artist-run non-profit organisation based in Tangiers, Morocco. She was the recipient of the Radcliffe Institute Fellowship from Harvard University (2017-2018). Her latest film installation is Twenty-Two Hours (2018). Dir/DoP: David Bickerstaff | 91′ | Art Doc in

Dir/DoP: David Bickerstaff | 91′ | Art Doc in A great collector himself, he was able to buy more painting through sales of his own work, indulging his passion for El Greco, Gauguin and Van Gogh. He idolised the work of Ingrès and his competitor Delacroix. He also developed a passion for photography and often used that to inform his own artwork, and many painters adopt this same technique in portrait painting today.

A great collector himself, he was able to buy more painting through sales of his own work, indulging his passion for El Greco, Gauguin and Van Gogh. He idolised the work of Ingrès and his competitor Delacroix. He also developed a passion for photography and often used that to inform his own artwork, and many painters adopt this same technique in portrait painting today.

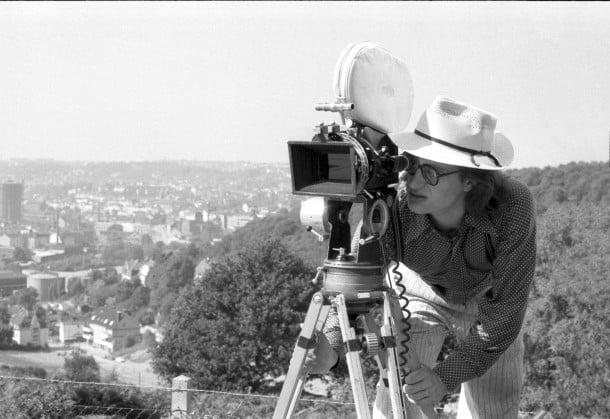

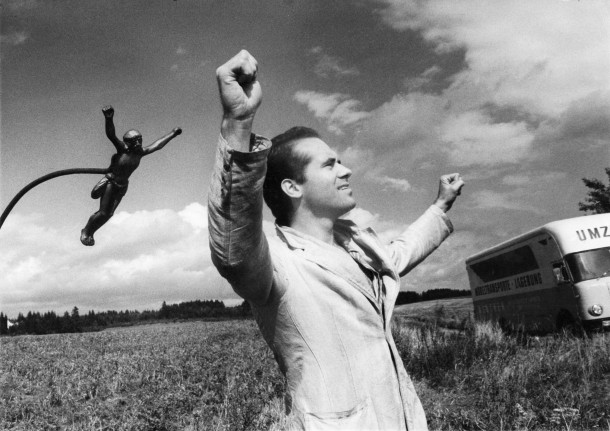

The first female director to win the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, Margarethe von Trotta (1942) is to thank for some of the most trailblazing films over the past five decades. Von Trotta’s wonderfully complex and outspoken female characters have undoubtedly inspired those taking centre stage in films by contemporary directors such as Jane Campion, Andrea Arnold, Lynne Ramsay and Lone Scherfig. One of the most gifted – but often overlooked – directors to emerge from the New German Cinema movement at the same time as Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Werner Herzog – von Trotta has never shied away from topics that resonate with contemporary lives and provoke revolutionary discussion. The power of mass media, historical events, radicalisation and women’s rights, have all been visible elements in her films since the politically turbulent 1970s.

The first female director to win the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, Margarethe von Trotta (1942) is to thank for some of the most trailblazing films over the past five decades. Von Trotta’s wonderfully complex and outspoken female characters have undoubtedly inspired those taking centre stage in films by contemporary directors such as Jane Campion, Andrea Arnold, Lynne Ramsay and Lone Scherfig. One of the most gifted – but often overlooked – directors to emerge from the New German Cinema movement at the same time as Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Werner Herzog – von Trotta has never shied away from topics that resonate with contemporary lives and provoke revolutionary discussion. The power of mass media, historical events, radicalisation and women’s rights, have all been visible elements in her films since the politically turbulent 1970s. ROSA LUXEMBURG (1986)

ROSA LUXEMBURG (1986) THE LOST HONOUR OF KATHARINA BLUM (1975)

THE LOST HONOUR OF KATHARINA BLUM (1975)

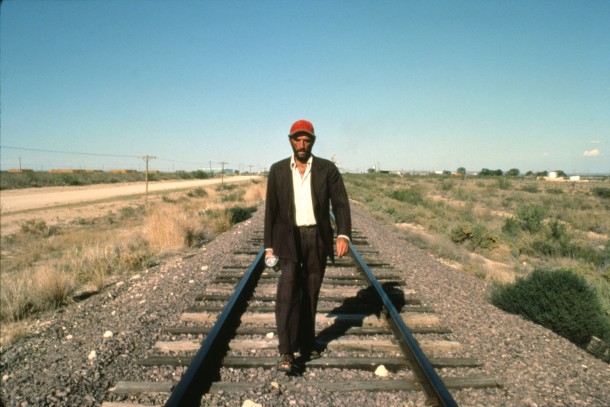

Vagabond

Vagabond

The Closing Night will be the UK Premiere of

The Closing Night will be the UK Premiere of  There will be two retrospectives in honour of non-fiction filmmaking: The innovative found footage documentarian Penny Lane and Japanese pioneer of ‘action documentary’, Kazuo Hara. Both filmmakers will be at the festival to present their work.

There will be two retrospectives in honour of non-fiction filmmaking: The innovative found footage documentarian Penny Lane and Japanese pioneer of ‘action documentary’, Kazuo Hara. Both filmmakers will be at the festival to present their work. Open City Documentary Festival is looking forward to hosting a number of exciting festival parties this year including the Opening and Closing Night Receptions at the Regent Street Cinema as well as the Nabihah Iqbal after-party at the ICA, where the DJ, Producer & NTS Radio presenter presents an evening of music inspired by 1972 documentary Winter Soldier, featuring protest songs and music from the anti-war movement from 1950-1975. Other various festival parties will be listed in the festival programme.

Open City Documentary Festival is looking forward to hosting a number of exciting festival parties this year including the Opening and Closing Night Receptions at the Regent Street Cinema as well as the Nabihah Iqbal after-party at the ICA, where the DJ, Producer & NTS Radio presenter presents an evening of music inspired by 1972 documentary Winter Soldier, featuring protest songs and music from the anti-war movement from 1950-1975. Other various festival parties will be listed in the festival programme. This early success led to various roles in TV and a film career that flourished with his performance in Ron Shelton’s popular sports film Bull Durham (1988). Proof of his undeniable talent followed with his role in the drama Jacob ’s Ladder (1990), and Robbins went on to work with legendary indie director Robert Altman – taking the sardonic lead role in Altman’s The Player (1992) which won him a Golden Globe and the Best Actor at the Cannes Film Festival.

This early success led to various roles in TV and a film career that flourished with his performance in Ron Shelton’s popular sports film Bull Durham (1988). Proof of his undeniable talent followed with his role in the drama Jacob ’s Ladder (1990), and Robbins went on to work with legendary indie director Robert Altman – taking the sardonic lead role in Altman’s The Player (1992) which won him a Golden Globe and the Best Actor at the Cannes Film Festival. There followed appearances in the Coen brothers’ The Hudsucker Proxy (1994), another outing with Robert Altman (the comedy from the world of fashion Prêt-à-Porter, 1994), and his work with Frank Darabont on The Shawshank Redemption (1994), which was nominated for seven Oscars. In 1996 Dead Man Walking earned him an Oscar nomination for best director, while his partner Susan Sarandon won an Oscar for best actress. His next auteur outing, Cradle Will Rock (1999) above, which premiered at Cannes, explored the relationship between the individual artist and society during a tumultuous time in the U.S. though this time in another era. As with Dead Man Walking, Robbins produced, and the music was written by his brother David.

There followed appearances in the Coen brothers’ The Hudsucker Proxy (1994), another outing with Robert Altman (the comedy from the world of fashion Prêt-à-Porter, 1994), and his work with Frank Darabont on The Shawshank Redemption (1994), which was nominated for seven Oscars. In 1996 Dead Man Walking earned him an Oscar nomination for best director, while his partner Susan Sarandon won an Oscar for best actress. His next auteur outing, Cradle Will Rock (1999) above, which premiered at Cannes, explored the relationship between the individual artist and society during a tumultuous time in the U.S. though this time in another era. As with Dead Man Walking, Robbins produced, and the music was written by his brother David. The section also presents the newest generation of filmmakers who began to work during the collapse of the Soviet Union and whose poetic style was significantly influenced by the New Wave of Baltic documentary film. Lithuanian documentarian Audrius Stonys will presents his film The Land of the Blind (1992), which earned him the European Film Academy’s Phoenix Award for Best Documentary Film, and also his later Anti-Gravitation (1995). We will also be showing renowned Latvian director Laila Pakalniņa’s trilogy The Linen, The Ferry and The Mail (1991–95), which launched her international film career (The Ferry and The Mail were screened as part of the Un Certain Regard section at the Cannes Film Festival).