Dir: Ferenc Török | Cast: Péter Rudolf, Bence Tasnádi, Tamás Szabó Kimmel, Dóra Sztarenki, Ági Szirtes, József Szarvas | Drama | Hungary 2017 | 91 min

Best known for his 2001 comedy drama Moscow Square, Ferenc Török has continued to hone his skills in TV work in his native Hungary. His latest film is an unsettling war-themed drama that takes place on the Hungarian puszta during the blistering heat of August 1945 where the local chemist is getting ready for his son’s wedding. In the sleepy afternoon torpor, two strange men arrive on the scene – and no one is glad to see them. As news of the Sámuels’ arrival seeps through the streets like a bad odour, these orthodox Jewish men dressed in black walk solemnly behind a horse drawn carriage, where their two wooden boxes – like children’s coffins – conceal a mysterious cargo. Clearly something has happened here that has left a sinister whiff of fear for all concerned, not least because of the local’s poor treatment of their Jewish neighbours during the war years. And as they past re-visits the present, the villagers know exactly why they should be scared.

Meanwhile, preparations for the evening wedding are underway. But the bride Kisrózsi (Dóra Sztarenki) is no virgin – she left her good-looking boyfriend Jancsi (Tamás Szabó Kimmel) to pursue a better offer from Arpad, who owns the profitable chemist store. But Arpad’s mother Anna (Eszter Nagy-Kálózy) has rumbled her and is well aware that Kisrózsi and Jancsi are still lovers. This appears to be a community seething in hatred, mistrust and envy, that comes from the outside and from within as they tolerate the constant strain of Soviet occupation.

The tone is very much like that of a darkly comic Midsommer Murders, as the Samuels’ tale intriguingly unfolds amidst a climate of fear and doom. Török and co-writer Gábor T. Szántó base their narrative on Homecoming, a short story where a guilty village serves as a metaphor for national shame, with each character determined to keep their secret in the face of the enemy they have wronged. DoP Elemér Ragályi’s beguiling black and white visuals recreate the 1940s in a mystery that relies on its ominous atmosphere and the strength of its performances, rather than dialogue, to tell a tale of vengeance and dishonour in post war Hungary.MT

NOW SCREENING NATIONWIDE from 12 October 2018

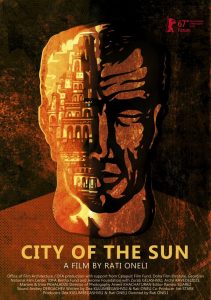

Dir: Rati Oneli | Georgia / USA / Qatar / Netherlands 2017 | Georgian | Doc | 104 min · Colour

Dir: Rati Oneli | Georgia / USA / Qatar / Netherlands 2017 | Georgian | Doc | 104 min · Colour