The German production TIGER GIRL by Jakob Lass will open this year’s edition of Panorama Special at Berlin’s Zoo Palast cinema, along with the previously announced Brazilian production VAZANTE.

In TIGER GIRL’s fast-paced narrative, a strong friendship develops between two women, one in which conventional value systems begin to unravel, in what amounts to a veritable moral portrait of the underbelly of today’s German republic. Daniela Thomas’ VAZANTE represents for its part the programme focus “Black Worlds”, which is also reinforced by the freshly confirmed inclusion of the South African production VAYA by Akin Omotoso, which offers an immersion in the urbanity of Johannesburg.

The fourth film from Brazil is COMO NOSSAS PAIS(Just Like Our Parents) by Laís Bodanzky, who depicts the everyday lives of three generations in Sao Paulo as a pyrotechnic display of individual passions and existential delusions staged with a sublime naturalness.

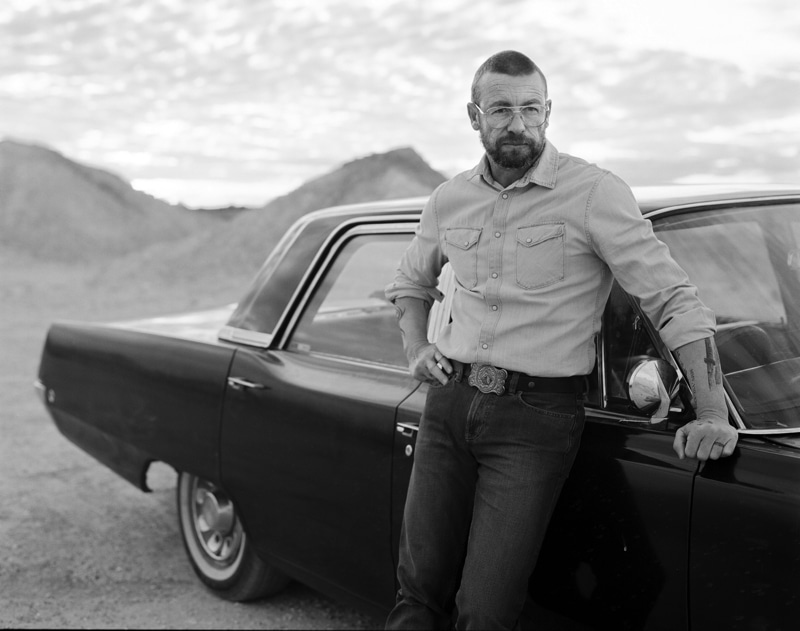

With DISCREET, US indie director Travis Mathews, a chronographer of a gay Western modernity, is showing his second film in Panorama. An eerie soundscape floats atop his often elliptically edited story, which revolves around a man approaching middle age who gets caught up in the darker depths of his past.

The original style of Moroccan filmmaker Hicham Lasri was already apparent at Panorama 2015 in The Sea is Behind and on display again last year in Starve Your Dog. Now he returns for the third time with Headbang Lullaby, a visually stunning psychedelic fairy tale swimming in vibrant colour and full of absurd situations, which also takes a long socially critical look at the history of Lasri’s native Morocco.

Naoko Ogigami already enchanted audiences in Berlin with Megane in 2008 and Rentaneko in 2012. In her most recent film Karera ga Honki de Amu toki wa (Close-Knit), the Japanese director employs contemplative, focussed imagery to honour a potential matter-of-factness for non-normative sexualities and the value of families that are defined by love and care and not by conventions.

Three modern arthouse films from China and Hong Kong shed some fresh light on the complex upheavals afoot throughout the vast country. Establishing alternatives for one’s self within authoritarian systems is a great step towards individual freedom: In Bing Lang Xue (The Taste of Betel Nut), we experience the whirlwind of young love on a resort island, while in Ghost in the Mountains and Ciao Ciao, a French co-production, we bask in the breath-taking landscapes of the Chinese highlands through the power of adept cinematography.

In his New Zealand film One Thousand Ropes, Samoan director Tusi Tamasese creates mythic images full of tension and concentration to relate the story of Maea, the baker and male midwife with the healing hands, whose personal demons play an integral role in his everyday life.

Today whole hordes of young cosmopolitans are drawn to Berlin by the promise of happiness that the city has come to represent – three films that pay tribute to this vision in extremely different manners are gathered at Panorama: the psycho thriller Berlin Syndrome by Australian director Cate Shortland, featuring Teresa Palmer, Max Riemelt and Matthias Habich; the feminist fairy tale The Misandrists by Berlinale regular Bruce LaBruce; and the para-pornographic work of underground science fiction Fluidø, by Taiwanese-American artist Shu Lea Cheang.

E U R O P E

Thirteen more films have been confirmed for the final selection from Europe alone. These include works like the Spanish debut feature Pieles (Skins) by Eduardo Casanova, Rekvijem za gospodju J. (Requiem for Mrs. J.) by Serbia’s Bojan Vuletić, Ferenc Török’s 1945 from Hungary and God’s Own Country, Francis Lee’s feature-film debut from United Kingdom. Teona Mitevska returns with a bitter depiction of Macedonian adolescents trying to get their bearings in When the Day Had no Name. Also returning to Panorama are Norwegians Ole Giæver, with the emancipatory and philosophical self-examination Fra balkongen (From the Balcony), and Erik Poppe with Kongens Nei (The King’s Choice), which deals with the Norwegian king’s resistance to the German armed forces in World War II.

Luca Guadagnino will show his French-Italian account of summer love, Call Me by Your Name featuring Armie Hammer, Timothée Chalamet, Michael Stuhlbarg and Amira Casar, a screen adaptation of André Aciman’s novel of the same name, co-written with James Ivory (left).

The Belgian-French-Lebanese co-production Insyriated by Philippe Van Leeuw is an intense chamber drama featuring Hiam Abbass as a woman trapped in the family’s apartment while a war rages on outside. Kaygı (Inflame) by Ceylan Özgün Özçelik tells the story of the incremental roll-out of wide-spread censorship of the press in Turkey and its effect on the work of a young female journalist. And finally there is Georgian director Rezo Gigineishvili’s Hostages, in which a longing for freedom and independence escalates into a readiness to use violence for young Soviet citizens during an airplane hijacking set in 1983.

Panorama main programme | Panorama Special

1945 – Hungary

By Ferenc Török

With Péter Rudolf, Bence Tasnádi, Tamás Szabó Kimmel, Dóra Sztarenki, Eszter Nagy-Kálózy

European premiere

THE BERLIN SYNDROME – Australia

By Cate Shortland

With Teresa Palmer, Max Riemelt

European premiere

THE TASTE OF BETEL NUT (main pic) Bing Lang Xue – Hong Kong, China

By Hu Jia

With Zhao Bing Rui, Yue Ye, Shen Shi Yu

World premiere

CALL ME BY YOUR NAME – Italy / France

By Luca Guadagnino

With Armie Hammer, Timothée Chalamet, Michael Stuhlbarg, Amira Casar, Esther Garrel, Victoire Du Bois

European premiere

CIAO-CIAO – France / People’s Republic of China

By Song Chuan

With Liang Xueqin, Zhang Yu

World premiere

JUST LIKE OUR PARENTS – Como Nossos Pais Brazil

By Laís Bodanzky

With Maria Ribeiro, Clarisse Abujamra, Paulo Vilhena, Felipe Rocha, Jorge Mautner, Herson Capri, Sophia Valverde, Annalara Prates

World premiere

DISCREET – USA

By Travis Mathews

With Jonny Mars, Atsuko Okatsuko, Joy Cunningham, Bob Swaffar

World premiere

FLUIDO – Germany

By Shu Lea Cheang

World premiere

Fra balkongen (From the Balcony) – Norway

By Ole Giaever

World premiere

GHOST IN THE MOUNTAINS – People’s Republic of China

By Yang Heng

With Tang Shenggang, Liang Yu, Shang Meitong, Xiang Peng, Zhang Yun

World premiere

GOD’S OWN COUNTRY – United Kingdom

By Francis Lee

With Josh O’Connor, Alec Secăreanu, Gemma Jones, Ian Hart

European premiere

HEADBANG LULLABY – Morocco / France / Qatar / Lebanon

By Hicham Lasri

With Aziz Hattab, Latefa Ahrrare, Zoubir Abou el Fadl, El Jirari Benaissa, Salma Eddlimi, Adil Abatorab

World premiere

HOSTAGES – Russian Federation / Georgia / Poland

By Rezo Gigineishvili

With Merab Ninidze, Darejan Kharshiladze, Tina Dalakishvili, Irakli Kvirikadze

World premiere

INSYRIATED – Belgium / France / Lebanon

By Philippe Van Leeuw

With Hiam Abbass, Diamand Abou Abboud, Juliette Navis, Mohsen Abbas, Moustapha Al Kar

World premiere

CLOSE-KNIT Karera ga Honki de Amu toki wa (Close-Knit) – Japan

By Naoko Ogigami

WithToma Ikuta, Rinka Kakihara, Kenta Kiritani

World premiere

INFLAME – Kaygı Turkey

By Ceylan Özgün Özçelik

With Algı Eke, Özgür Çevik

World premiere– Debut film

THE KING’s CHOICE Kongens Nei – Norway / Sweden / Denmark / Ireland

By Erik Poppe

With Jesper Christensen, Anders Baasmo Christiansen, Karl Markovics, Tuva Novotny, Katharina Schüttler, Juliane Köhler

European premiere

THE MISANDRISTS – Germany

By Bruce LaBruce

With Susanne Sachsse, Kembra Pfahler

World premiere

ONE THOUSAND ROPES – New Zealand

By Tusi Tamasese

With Uelese Petaia, Frankie Adams, Væle Sima Urale, Ene Petaia, Beulah Koale, Anapela Polataivao

World premiere

PIELES (Skins) – Spain

By Eduardo Casanova

with Ana Polvorosa, Candela Peña, Carmen Machi, Macarena Gómez, Secun de la Rosa, Jon Kortajarena, Antonio Duran “Morris”, Eloi Costa

World premiere – Debut film

REQUIEM FOR MRS J Rekvijem za gospodju J. – Serbia / Bulgaria / Macedonia / Russian Federation / France

By Bojan Vuletić

With Mirjana Karanović, Jovana Gavrilović, Danica Nedeljković, Vučić Perović

World premiere

TIGER GIRL – Germany

By Jakob Lass

With Ella Rumpf, Maria Dragus

World premiere

VAYA – South Africa

By Akin Omotoso

With Mncedisi Shabangu, Zimkhitha Nyoka, Nomonde Mbusi, Sihle Xaba, Warren Masemola,

Zimkhitha Nyoka, Nomonde Mbusi, Azwile Chamane

European premiere

WHEN THE DAY HAD NO NAME – Macedonia / Belgium / Slovenia

By Teona Mitevska

With Leon Ristov, Hanis Bagashov, Dragan Mishevski, Stefan Kitanovic, Igorco Postolov, Ivan Vrtev Soptrajanov

World premiere

Supporting Film

VENUS – Filó a fadinha lésbica (Venus – Filly the Lesbian Little Fairy) – Brazil

By Sávio Leite

Already Announced Titles

CENTAUR – Kyrgyzstan / France / Germany / The Netherlands, by Aktan Arym Kubat

HONEYGIVER AMONG THE DOGS – Bhutan, by Dechen Roder

PENDULAR – Brazil / Argentinia / France, by Julia Murat

THE – South Africa / Germany / The Netherlands / France, by John Trengove

VAZANTE – Brazil / Portugal, by Daniela Thomas

BERLINALE 2017 | PANORAMA SECTION | 9-19 FEBRUARY 2017