Britain’s best-loved, independent cinema organisation, EALING STUDIOS, produced a dazzling array of comedies and noirish dramas during the 1940s and 50s, adding a rich vein of provocative and subversive films to the British film canon, some of them surprisingly radical in their implications.

Britain’s best-loved, independent cinema organisation, EALING STUDIOS, produced a dazzling array of comedies and noirish dramas during the 1940s and 50s, adding a rich vein of provocative and subversive films to the British film canon, some of them surprisingly radical in their implications.

The Studios has a unique place in the history of British cinema and has become a byword for a certain type of British whimsy and eccentricity but it also pioneered the underdog spirit, producing some tough, cynical and challenging portraits of British life. During the War years, Ealing produced romantic features that roused the British public during the War effort and the studio’s films boasted a surprising variety of characters from all walks of life. Many of these now rank among the undisputed cult classics of British cinema, among them Dead of Night, The Blue Lamp, The Cruel Sea, The Man in the White Suit and Passport to Pimlico. There are many other worthwhile features that have been unseen or inaccessible for decades.

IT ALWAYS RAINS ON SUNDAY (1947) Set over a single 24-hour period in postwar Bethnal Green, Robert Hamer’s noir-ish thriller was Ealing Studios’ first popular success and it widely considered one of the greatest achievements of British Cinema of the last 1940s.

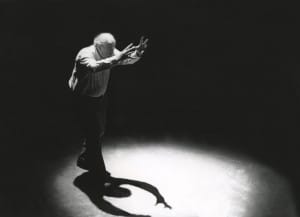

Ealing was presided over by Michael Balcon, a towering figure in British cinema who was an early supporter of Alfred Hitchcock. He gathered around him a band of talented collaborators including the very influential Braziilian Cavalcanti brothers and directors Charles Crichton, Robert Hamer, Basil Dearden and Alexander McKendrick. Battling against competition and a certain hostility from the major studios of Rank and the American giant Hammer he successfully ran Ealing for more than 20 years.

Today Ealing Studios is the oldest working film studio in the world and the only British studio that produces and distributes feature films as well as providing facilities. It recently joined forces with leading film financier Prescience, co-formed in 2005 by Paul Brett and Tim Smith, to create the new one-stop international sales company ‘Ealing Metro’. Prescience uniquely positions Ealing Metro as an international sales and distribution company that can deliver an integrated solution for filmmakers. Through Prescience and its Aegis Film Fund, Ealing Metro works with independent producers to help develop and finance product so that, along with Ealing Studios’ own productions, it can market and sell a unique and growing slate in the international marketplace.

The theme of Ealing: Light & Dark is a rich and revealing one. Even the renowned comedies have a dark side within them: Kind Hearts and Coronets is a wittily immoral tale of a serial killer in pursuit of a dukedom; Whisky Galore! has a mischievous approach to law and order as a Scottish island population attempt to beat the Customs men to the free whisky washed ashore from a shipwreck.

Part of the enduring appeal of Ealing is its witty challenging of authority in films such as Passport to Pimlico and The Lavender Hill Mob, which touched a nerve with audiences eager for social and political change faced with the austerity of the immediate post-war era.

Beyond the apparent frothy entertainment, Ealing’s darker side dares to show wartime failures, imagine the threat of invasion or to contemplate the unsavoury after-effects of the war in the subtly supernatural The Ship That Died of Shame or the European noir Cage of Gold, in which Jean Simmons is lured by the charms of an homme fatal. Another pan-European story, Secret People (featuring an early appearance for Audrey Hepburn), contemplates the ethics of assassination, while in Frieda, Mai Zetterling faces anti-German prejudice in a small English town.

The posters for Ealing Studios films feature artwork by many of the era’s greatest artists including John Piper, Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious, Edward Ardizzone and Mervyn Peake, while the acting talent is a roll-call of many of Britain’s greatest performers, among them Alec Guinness, Stanley Holloway, Margaret Rutherford, Joan Greenwood, Dennis Price, Jean Simmons, Googie Withers, Michael Redgave, John Mills, Thora Hird, Diana Dors, James Fox, Virginia McKenna, Herbert Lom, Maggie Smith, Jack Warner, Alastair Sim, Will Hay and many more.

E A L I N G F I L M N O I R

NEXT OF KIN

UK 1942. Dir Thorold Dickinson. With Mervyn Johns, Guy Mas, Basil Radford,

Nova Pilbeam, Thora Hird. 102min

Ealing’s first major artistic triumph for the war effort, Next of Kin is a cautionary tale about careless talk and the scourge of fifth columnists at large in the UK. The film’s sober tone marked a change in war propaganda for Ealing, whose earlier blind celebration of military prowess gives way to an authentic depiction of the dangers and sacrifices faced by the wartime nation. Plus All Hands (UK 1941. Dir John Paddy Carstairs. 9min) a MoI short that warns of the dangers of careless talk in the navy.

WENT THE DAY WELL? UK 1942.

WENT THE DAY WELL? UK 1942.

Dir Alberto Cavalcanti. With Leslie Banks, Basil Sydney, Frank Lawton, Elizabeth Allan. 93min. PG

In the middle of World War II Cavalcanti provocatively imagined a postwar England in which the failure of the threatened German invasion could be safely seen in flashback, thanks to the resourceful villagers of Bramley End. Once the ostensibly British troops in their village are revealed as Nazis, and the local squire as a fifth columnist, the community unites and fights back with startling ferocity. A call to arms as persuasive as Powell and Pressburger’s The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp.

DEAD OF NIGHT

UK 1945. Dir Alberto Cavalcanti. With Googie Withers, Mervyn Johns, Michael Ralph, Michael Redgrave. 102min

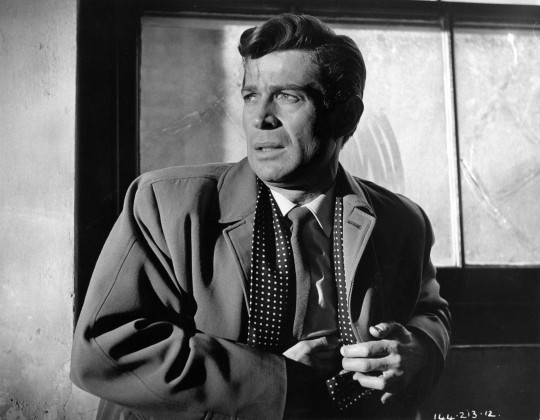

Straying from more familiar realist fare, Dead of Night was Ealing’s only venture into the horror genre. The film recounts five supernatural tales, held together by a linking story which itself has a creepy conclusion – a forerunner to the anthology films that flourished in the early 1970s. The film’s nightmarish world of haunted mirrors and ghostly hearses lingers long after the closing credits, with Michael Redgrave’s performance as a crazed ventriloquist proving particularly unsettling.

PINK STRING AND SEALING WAX

UK 1945. Dir Robert Hamer. With Googie Withers, Mervyn Johns, Gordon Jackson, Sally Ann Howes. 89min. PG

Two worlds collide in this melodrama set in Victorian Brighton: a repressive household, run by a tyrannical chemist, and a sleazy tavern, presided over by a passionate landlady. The chemist’s son (Jackson) finds himself, understandably enough, in thrall to the landlady (Withers). His naïve passion and rebellious feelings against his father lead him into a murder plot from which he barely escapes, prompting a very equivocal happy ending.

FRIEDA

UK 1947. Dir. Basil Dearden. With David Farrar, Glynis Johns, Mai Zetterling, Flor Robson. 98min. PG

Telling the story of a family trying to make sense of a postwar world, Frieda asks the question, ‘Does a good German exist?’ There isn’t one simple answer but many, represented by the varying reactions of the inhabitants of the English village of Denfield when a German refugee arrives as the wife of one of their war heroes. In her first British film, Zetterling portrays Frieda sympathetically but the film allows the audience to reach its own conclusion over her individual responsibility for the horrors of war.

SARABAND FOR DEAD LOVERS

SARABAND FOR DEAD LOVERS

UK 1948. Dir Basil Dearden. With Joan Greenwood, Stewart Granger, Peter Bull,Flora Robson. 96min. U

In this rare excursion for Ealing into historical drama, Bull and Greenwood are perfectly cast as the dissolute Prince George-Louis and his reluctant bride Sophie-Dorothea. Shooting in colour for the first time allowed the studio to give full rein to the period costumes and sets (the latter were nominated for an Oscar). The design provides an evocative backdrop to the princess’s tragic story. As her lover, Granger shows why he was soon poached by Hollywood, his stature and looks making him the perfect screen hero.

WHISKY GALORE!

UK 1949. With Basil Radford, Joan Greenwood, Wylie Watson, Bruce Seaton,

Gordon Jackson. 82min. PG

Mackendrick’s glorious debut was the second of the trio of 1949 films that defined Ealing Comedy. When the whisky-parched Todday islanders spy salvation in the form of a shipwreck and 50,000 contraband cases, first they must outwit the morally upstanding English home guard Captain Waggett. One in the eye for puritan English priggishness and a joyous salute to the transformative power of a ‘wee dram’ – or ‘the longest unsponsoredadvertisement ever to reach cinema screens the world over,’ as producer Monja Danischewsky put it.

KIND HEARTS AND CORONETS

UK 1949. Dir Robert Hamer. With Dennis Price, Alec Guinness, Joan Greenwood,

Valerie Hobson. 106min. U

Even Hitchcock couldn’t make murder this much fun. Hamer’s ageless classic challenges The Ladykillers for the title of Ealing’s blackest comedy (call it a score draw, though Kind Hearts has the higher body count). Near perfect script and direction are crowned by wondrous performances. History tends to remember Guinness’s virtuoso turn as all seven members of the lofty, aristocratic D’Ascoynes. But it’s really Price’s film: as the D’Ascoynes’ ruthless nemesis Louis he gives us surely the screen’s wittiest and most charming psychopath.

CAGE OF GOLD

UK 1950. Dir Basil Dearden. With Jean Simmons, David Farrer, James Donald,

Herbert Lom. 83min. PG

Simmons’s only film for Ealing is an unfairly neglected slice of Euro-noir, built upon the (apparently) un-Ealing foundations of passion, infidelity and blackmail. Simmons is a nice, middle-class girl with a nice, steady fiancé who is enticed to the dark side by the return of an old flame. The film flits between cosy suburbia and a vivid Parisian demi-monde, and if the conclusion inevitably opts for safety, the alternative is painted with relish, and Farrer, as ever, makes an appealing rogue.

THE MAN IN THE WHITE SUIT

UK 1951. Dir. Alexander McKendrick. With Alec Guinness, Joan Greenwood, Cecil Parker, Michael Gough,Ernest Thesiger. 85min. U

Mackendrick’s plague-on-all-your houses industrial satire may be the most cynical Ealing film of all. Guinness delivers his most complex comic performance as the unworldly genius Sidney, whose invention of an indestructible, dirt-proof fabric terrifies textile barons and trade unions alike. A parable of the inexorability of technological progress and the tyranny of vested interests – with some sly sexual politics thrown in – it’s as acerbic a piece of social commentary as ever escaped from Ealing.

SECRET PEOPLE

UK 1952. Dir Thorold Dickinson. With Valentina Cortese, Serge Reggiani, Charles

Goldner. 96min. PG

An untypical Ealing film, drawing on Dickinson’s own Spanish Civil War experiences. Maria (Cortese), orphaned in London, is a hesitant revolutionary enlisted by her lover to assassinate her country’s fascist leader, the man responsible for her father’s death. Compelling and strikingly inventive, Secret People upset contemporary critics for its apparent indecision, but today it seems an intriguing study of a moral dilemma, with engaging performances from its Italian leads and a notable early role for young Audrey Hepburn.

MANDY

UK 1952. With Phyllis Calvert, Jack Hawkins, Terence Morgan, Mandy Miller,

Edward Chapman. 93min. PG

In this rare Ealing tearjerker, Calvert and Morgan play a couple who disagree about how best to help their deaf child; their relationship is strained further when they become pawns in a political situation at a special school. The story is presented largely from the female point of view and Calvert gives an exceptionally moving performance as the mother torn between her husband and her child. Mandy never succumbs to mawkishness, approaching the subject with sensitivity and reason.

THE CRUEL SEA

THE CRUEL SEA

UK 1952. Dir Charles Frend. With Virginia McKenna, Stanley Baker. 126min

The ‘Battle of the Atlantic’, as experienced by the captain and first

lieutenant of an anti-submarine convoy escort. Based on Nicholas

Monsarrat’s novel, Ealing’s most popular war film celebrates the commitment and bravery of the British naval forces but isn’t afraid to engage with the harsh realities of combat. Jack Hawkins and Donald Sinden lend British grit to the military spectacle and claustrophobic tension, depicting those men shaped and permanently shadowed by the war.

THE MAGGIE

UK 1954. With Paul Douglas, Alex Mackenzie, Abe Barker, Tommy Kearins,

Hubert Gregg. 92min. U

An unsentimental counterpart to Ealing’s The Titfield Thunderbolt, with the latter’s vintage steam train crewed by high-spirited amateurs replaced by a ramshackle ‘puffer’ boat and its gnarly old skipper. The devious MacTaggart cheats his way to the commission to transport a US businessman’s cargo – the first in a series of indignities heaped on his hapless client. The Maggie pits wealth and modernity against heritage and intransigence in a gleeful subversion of Ealing’s ‘small versus big’ convention.

THE SHIP THAT DIED OF SHAME

UK 1955. Dir Basil Dearden. With George Baker, Richard Attenborough, Bill Owen,

Virginia McKenna. 95min

Director Basil Dearden combines sharp thrills with loose social commentary in this tale of Motor Gun Boat 1087 and her once-celebrated officers now turned smugglers. Ealing’s occasional engagement with the supernatural and nostalgia for the war is spun into one of the studio’s darkest and best final films. Richard Attenborough is on form as a crooked chancer making the best out of the bleak social realities of postwar Britain.

NOWWHERE TO GO

NOWWHERE TO GO

UK 1958. Dir Seth Holt. With George Nader, Maggie Smith, Bernard Lee, Bessie

Love. 97min. U

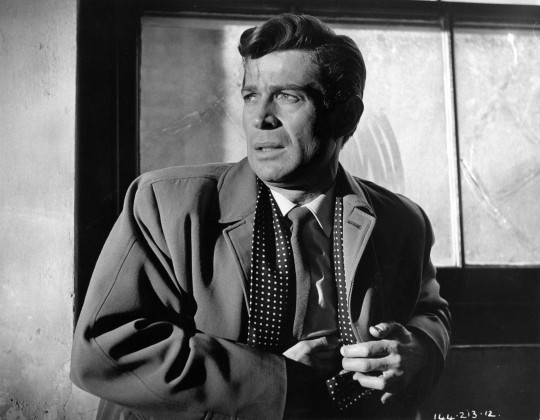

A rare, late excursion into noir for Ealing Studios, scripted by first-time director Holt and critic Ken Tynan. A good-looking ex-con (Nader) coolly robs an old lady of her coin collection, anticipating prison, but also the later recovery of the proceeds. Nothing proves that simple and he discovers the truth of the film’s title. Stylish low-key cinematography, a jazz score and Maggie Smith’s debut performance add to the pleasure.

EALING DRAMAS

THERE AIN’T NO JUSTICE

UK 1939. Dir Penrose Tennyson. With James Hanley, Edward Rigby, Edward Chapman, Mary Clare. 81 min

An aspiring boxer hopes to transcend humble origins and build a name for himself, but comes up against the corruption of the sporting establishment. ‘The film that begs to differ’, announced the publicity for this first film by Ealing’s youngest director, the gifted 25-year-old Pen Tennyson, great-grandson of Lord Alfred. It’s a striking departure from the shallow representation of working-class life in 1930s British films, and the first film to set out recognisably Ealing values: decency, courage and an optimistic faith in humanity and community.

CHEER BOYS CHEER

CHEER BOYS CHEER

UK 1939. Dir Walter Forde. With Edmund Gwenn, Peter Coke, Nova Pilbeam, 84 min.

An ‘Ealing comedy’ before its time? Venerable family brewery Greenleaf finds itself under threat from monopolistic industry titan Ironside. But with an unlikely ally in Ironside’s lovelorn scion, plucky little Greenleaf mounts a courageous fightback. Predating Passport to Pimlico and its comic cohort by a decade, this half-forgotten film was an almost uncanny premonition of Ealing delights to come, in its evocation of community, gently progressive values and ‘small v. big’ dynamic. A missing link in the Ealing story, then, but thanks to comedy veteran Forde, a joyous one.

THE BELLS GO DOWN

THE BELLS GO DOWN

UK 1943. Dir Basil Dearden. With Philip Friend, Tommy Trinder, James Mason, Mervyn Johns. 90 min.

“In the East End they say London isn’t a town, it’s a group of villages,” begins Dearden’s tribute to the intrepid firefighters confronting the Luftwaffe’s nightly raids. Village London is a very Ealing conception: the vast, anonymous city reduced to a more human scale. But The Bells Go Down is no mere sentimental homily. Its community has its share of divisions, petty squabbles and criminality, but these fade in the face of a common enemy and the stoic endurance of routine tragedy. An inspiring companion piece to Humphrey Jennings’ Fires Were Started.

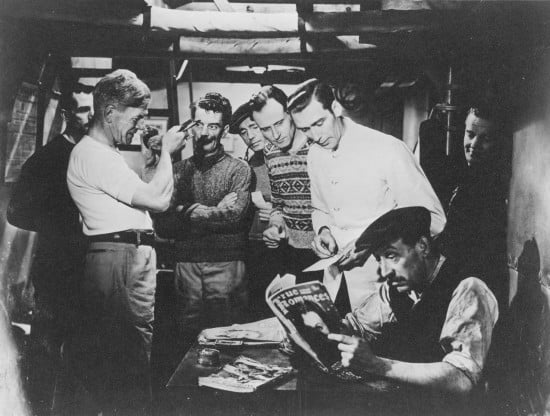

SAN DEMETRIO LONDON

SAN DEMETRIO LONDON

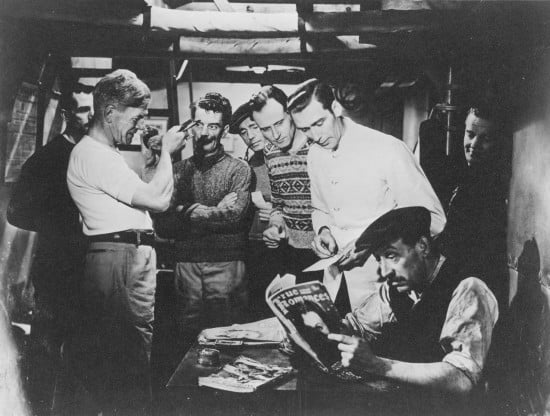

UK 1943. Dir Charles Frend. With Ralph Michael, Walter Fitzgerald, Robert Beatty, Gordon Jackson. 104 min.

In 1940 the oil tanker San Demetrio, half torn apart by U-boat torpedoes but still somehow afloat, was valiantly rescued by a handful of its crew and steered home through treacherous Atlantic waters. Frend’s admirable second feature takes a true story of wartime heroism and, without sensationalism or triumphalism, shapes it into something approaching national myth (the damaged but defiant ship stands for Britain, the crew a people united by determination, courage and democratic values). It’s Ealing’s most potent and inspiring fusion of propaganda, documentary and people’s war ideals.

THEY CAME TO A CITY

UK 1944. Dir Basil Dearden. With Googie Withers, John Clements, Raymond Huntley, Renée Gadd. 78 min.

This most unusual of Ealing’s features has long been hard to see and is now in a new digital transfer. A fantastical allegory from the pen of J.B. Priestley, it transports nine disparate Britons to a mysterious city. What they find there is, according to their class and disposition, either an earthly paradise of peace and equality or a hell starved of ambition and riches. A film once dismissed as naïve and uncinematic, it has more recently been viewed as a striking expression of its era’s most utopian impulse.

THE BLUE LAMP

UK 1950. Dir Basil Dearden. With Jack Warner, Dirk Bogarde, James Hanley, Peggy Evans. 82 min.

Ealing’s defining contribution to the police procedural genre – with ex-policeman T.E.B. Clarke’s script lending authenticity – sits on the border between the studio’s dark and light sides. There’s tragedy at its core, and a portrait of snarling, lawless youth (a mesmerising young Dirk Bogarde) that’s tough for its time, not least for Ealing. But if it takes us to dark places, its conclusion expresses an irrepressibly optimistic and comforting vision of the ability of society to overcome its most hostile elements.

THE PROUD VALLEY

UK 1940. Dir Pen Tennyson. With Paul Robeson, Simon Lack, Edward Chapman, Janet Johnson. 77 min.

An American seaman is welcomed into a Welsh mining village and bolsters a community facing industrial decline and the tremors of war. Paul Robeson brings warmth, integrity and powerful bass tones to his role as David Goliath, the figure around whom the struggling miners unite and discover their own proud voices. Pen Tennyson directs this simple story with compassion, beauty and dignity to make The Proud Valley one of the most satisfying of early Balcon-era Ealing.

THE HALFWAY HOUSE

THE HALFWAY HOUSE

UK 1944. Dir Basil Dearden. With Mervyn Johns, Francoise Rosay, Glynis Johns, Esmond Knight. 96 min.

Towards the end of the war, Ealing films took a positive turn and The Halfway House uses a ghostly setting to look towards a future in which wartime problems such as black marketeering, broken relationships and mourning for lost ones are left behind. A disparate group of people find themselves at a remote inn in the Welsh valleys which turns out not to be quite what it seems. A fine ensemble cast balances the film’s humour with its more serious undertones and the supernatural atmosphere is reinforced by a haunting score.

THE OVERLANDERS

THE OVERLANDERS

UK 1946. Dir Harry Watt.

With Chips Rafferty, Daphne Campbell, John Fernside, John Nugent Hayward, Peter Pagan. 91 min.

A band of Australian drovers, led by Dan McAlpine (Chips Rafferty), drive 1000 cattle across the harsh Northern Territory to fresh pastures in Brisbane. Ealing’s first Australian production is a stellar tribute to the country’s WWII scorched earth defence against the Japanese. Rafferty embraces the sprit of defiance that characterised a nation under threat of invasion, while director Harry Watt brings a documentary sensibility that celebrates the sheer ambition and vast achievement of the drive.

HUE AND CRY

HUE AND CRY

UK 1946. Dir Charles Crichton. With Harry Fowler, Jack Warner, Alastair Sim 82 min Script: T E B Clarke

In the first of the EALING COMEDIES, Harry Fowler leads the ‘Blood and Thunder Boys’, a group of adolescents who discover their favourite boys-own magazine is being used by criminals to plan robberies. Largely acknowledged as the first in Ealing’s cycle of post-war comedies, Hue and Cry gives us a joyfully chaotic of the kind of English eccentrics which would come to characterise the later films. Alistair Sim and Jack Warner are the old hands whose exaggerated performances lead a cast of mostly newcomers.

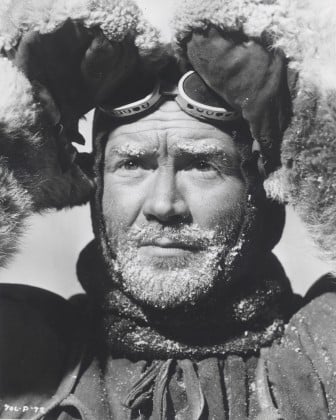

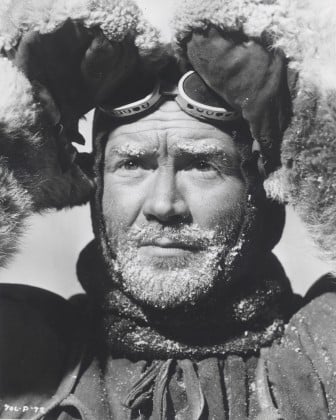

SCOTT OF THE ANTARCTIC

UK 1948. Dir Charles Frend. With John Mills, Kenneth More, John Gregson, James Roberston Justice. 109 min.

Michael Balcon’s self-confessed preference was for tales of adventure and derring-do and Scott fits the bill perfectly. The British spirit of endeavour and determination, even to the point of foolhardiness, pervades the film, as Scott’s expedition gets ever closer to failure. Filming in Technicolor was an interesting choice given the bleak locations but the scenery is captured exquisitely and offers a dramatic backdrop to the exploits of the party. Vaughan Williams’ score heightens the drama so poignantly enacted by Mills and the rest of the sterling cast.

PASSPORT TO PIMLICO

PASSPORT TO PIMLICO

UK 1949. Dir Henry Cornelius. With Stanley Holloway, Margaret Rutherford, Jane Hylton, Paul Dupuis. 84 min.

A group of Pimlico residents discover that they are in fact citizens of the Duchy of Burgundy, a change of nationality that offers them the opportunity to dodge post-war strictures. Tearing up their ration books, they embark on self-governance but soon find that, despite all its problems, Blighty is the best place to be. Cornelius’s only directing credit for Ealing (though he went on to success with Genevieve), Passport to Pimlico is perhaps the studio’s most joyous celebration of Britishness.

THE MAGNET

THE MAGNET

UK 1950. Dir Charles Frend. With William Fox, Stephen Murray, Kay Walsh, Meredith Edwards. 79 min.

James Fox, (credited here as William) plays Johnny, a 10-year-old who tricks a younger boy into giving him a toy magnet. Feeling guilty over his deception Johnny anonymously offers the magnet to auction, but when it raises raise enough funds to buy a life saving piece of hospital equipment he is nowhere to be found. A comedy of childhood errors, The Magnet pokes fun at a cosy adult world made insensible by the fantasies of some of its younger inhabitants. Ealing regulars Gladys Henson, Thora Hird and a disguised James Robertson Justice provide support.

THE LADYKILLERS

UK 1955. With Alec Guinness, Herbert Lom, Cecil Parker, Peter Sellers, Danny

Green, Katie Johnson. 97min. U

Everyone’s favourite knockabout black comedy caper – or a political fable with the ‘ladykillers’ as the incoming post-war Labour government and the little old ladies as the obstacles of Conservative tradition? Beyond any doubt The Ladykillers is the last great Ealing comedy, and the studio’s final production before its sale to the BBC.American screenwriter William Rose apparently dreamed up the plot overnight, but casting, script, production design, and the Technicolor camerawork combine effortlessly for the blackest of farces.

Rivalling Kind Hearts and Coronets for the gleeful blackness of its humour. Posing as an amateur string quintet while planning a robbery at Kings Cross, an ill-assorted group of crooks led by the sinister Professor Marcus (Guinness) rent rooms from a sweet little old lady (Johnson). Despite a few setbacks, the Professor’s plan works superbly. But there’s one factor he hasn’t allowed for… At 77, veteran bit-part player Johnson all but walks off with the film.

THE LAVENDER HILL MOB

THE LAVENDER HILL MOB

UK 1951. Dir Charles Crichton. With Alec Guinness, Stanley Holloway, Sidney James, Alfie Bass. 78 min.

Ealing’s theme of the ‘little man fighting back’ finds its culmination here, as upstanding citizens Guinness and Holloway turn to crime, hooking up with two small time crooks to form a gang of unlikely gold smugglers. The heroes’ dreams of freeing themselves from wage slavery in a grey, bombed out London have us rooting for them against the inept police pursuit. Writer T. E. B. Clarke’s comic observations are spot on; he creates a postwar Britain in which demure-looking little old ladies devour American detective fiction with relish.

THE TITFIELD THUNDERBOLT

THE TITFIELD THUNDERBOLT

UK 1952. Dir Charles Crichton. With Stanley Holloway, George Relph, John Gregson, Hugh Griffith, Sid James. 87 min.

The commuters of Titfield form an amateur rail company when they discover that their local branch line is to close. Despite physical opposition from a rival bus company, the train enthusiasts unite behind their eccentric village vicar (Relph) and his affable drunk benefactor (Holloway), to bumble their way to an operators licence. Perhaps the archetype of ‘Ealing Light’ Crichton’s gentle and nostalgic film was also the studio’s first made in colour.

Many of these films are available on DVD/Blu atand HUE and CRY, THE LADYKILLERS, THE MAGNET are re-released by STUDIO CANAL in June\July 2015

Lolita opens with a murder: a drunk elderly man is shot dead while playing Chopin on the piano. Then the linear events leading to this crime unfold: A lecturer in French literature Humbert Humbert (Mason), arrives in Ramsdale, New Hampshire, in search for lodgings. On the verge of turning down the rooms on offer from Charlotte Haze (Winters), he is just about to reject them, when he sees her daughter Dolores ‘Lolita’ (Lyon) and falls in love. But Charlotte has a shine for Humbert too, and drives her daughter to a girl’s camp, leaving a letter for Humbert, telling him to move out – or marry her. Humbert, still obsessed with Lolita, then marries Charlotte who later reads his diary where he confesses to his love for the school girl. Charlotte runs out of the house to post a letter to the authorities, but is killed in a car crash. Humbert fetches Lolita from the camp, pretending that her mother is in hospital, but seduces the girl in a motel. They set off on a romantic adventure, and are followed by an obnoxious stranger. In the autumn, Humbert enrols Lolita in a nearby High School where she is to participate in a school play. A discussion with Dr, Zempf (Sellers) upsets Humbert and he takes Lolita out of the school, touring the country again. Finally, Lolita disappears; leaving Humbert desolate. Much later, he learns that she is pregnant, living in a tranquil suburb. He gives her money, from the sale of her mother’s house, but she wants to stay with her husband Dick. She also tells Humbert that she ran away with Clare Quilty (Sellers), a famous playwright, who impersonated Dr. Zempf and followed them on their journeys. Humbert dies before the murder trial.

Lolita opens with a murder: a drunk elderly man is shot dead while playing Chopin on the piano. Then the linear events leading to this crime unfold: A lecturer in French literature Humbert Humbert (Mason), arrives in Ramsdale, New Hampshire, in search for lodgings. On the verge of turning down the rooms on offer from Charlotte Haze (Winters), he is just about to reject them, when he sees her daughter Dolores ‘Lolita’ (Lyon) and falls in love. But Charlotte has a shine for Humbert too, and drives her daughter to a girl’s camp, leaving a letter for Humbert, telling him to move out – or marry her. Humbert, still obsessed with Lolita, then marries Charlotte who later reads his diary where he confesses to his love for the school girl. Charlotte runs out of the house to post a letter to the authorities, but is killed in a car crash. Humbert fetches Lolita from the camp, pretending that her mother is in hospital, but seduces the girl in a motel. They set off on a romantic adventure, and are followed by an obnoxious stranger. In the autumn, Humbert enrols Lolita in a nearby High School where she is to participate in a school play. A discussion with Dr, Zempf (Sellers) upsets Humbert and he takes Lolita out of the school, touring the country again. Finally, Lolita disappears; leaving Humbert desolate. Much later, he learns that she is pregnant, living in a tranquil suburb. He gives her money, from the sale of her mother’s house, but she wants to stay with her husband Dick. She also tells Humbert that she ran away with Clare Quilty (Sellers), a famous playwright, who impersonated Dr. Zempf and followed them on their journeys. Humbert dies before the murder trial. The festival will open at the Barbican on 14 March with Hans Pool’s Bellingcat – Truth in a Post-Truth World, which follows the revolutionary rise of the “citizen investigative journalist” collective known as Bellingcat, dedicated to redefining breaking news by exploring the promise of open source investigation.

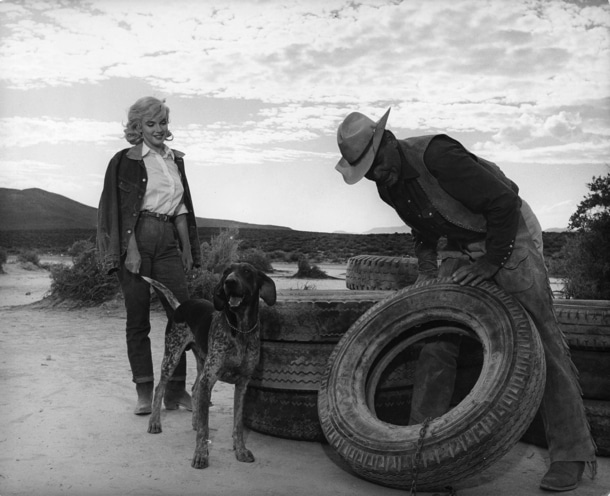

The festival will open at the Barbican on 14 March with Hans Pool’s Bellingcat – Truth in a Post-Truth World, which follows the revolutionary rise of the “citizen investigative journalist” collective known as Bellingcat, dedicated to redefining breaking news by exploring the promise of open source investigation.  Diva, grande dame and femme fatale, Stanwyck adapted to any genre, be it comedy, melodrama or thriller. Her natural wit and raw emotion was particularly resonant in her Westerns, where she played resourceful, confident women holding their own in a male-dominated world. The BFI are screening 3 examples in March. Her first western Annie Oakley (George Stevens, 1935) was based on the life of ‘Little Miss Sureshot,’ one of the most famous sharpshooters in American history; Stanwyck oozes confidence in her portrayal of the determined and spirited protagonist. Cecil B. DeMille brought a characteristically epic sense of scale to the western with Union Pacific (1939), about the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad. Mixed in with the historical elements is a love triangle between a troubleshooter, a gambler, and a train engineer’s daughter played by Stanwyck. The director was mesmerised by her performance, and she became one of his favourite stars. In Forty Guns (Samuel Fuller, 1957), a late-career highlight for Stanwyck, she portrays a wealthy landowner exerting influence over an Arizonian township by commanding a staff of 40 men. Beautifully shot and packed with psychosexual subtext and directed with bravura, Samuel Fuller’s western influenced a generation of filmmakers, including Godard.

Diva, grande dame and femme fatale, Stanwyck adapted to any genre, be it comedy, melodrama or thriller. Her natural wit and raw emotion was particularly resonant in her Westerns, where she played resourceful, confident women holding their own in a male-dominated world. The BFI are screening 3 examples in March. Her first western Annie Oakley (George Stevens, 1935) was based on the life of ‘Little Miss Sureshot,’ one of the most famous sharpshooters in American history; Stanwyck oozes confidence in her portrayal of the determined and spirited protagonist. Cecil B. DeMille brought a characteristically epic sense of scale to the western with Union Pacific (1939), about the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad. Mixed in with the historical elements is a love triangle between a troubleshooter, a gambler, and a train engineer’s daughter played by Stanwyck. The director was mesmerised by her performance, and she became one of his favourite stars. In Forty Guns (Samuel Fuller, 1957), a late-career highlight for Stanwyck, she portrays a wealthy landowner exerting influence over an Arizonian township by commanding a staff of 40 men. Beautifully shot and packed with psychosexual subtext and directed with bravura, Samuel Fuller’s western influenced a generation of filmmakers, including Godard.