D R A C U L A T H R O U G H T H E A G E S : Leaves from Stoker’s Book

First published in 1897, Bram Stoker’s DRACULA is now seen as one of the canonical texts of Gothic literature, but it was only long after Stoker’s death that the work took on iconic status – thanks in no small part to the numerous films that proliferated as the Count’s cultural clout increased (there have now been over 200). To explain the appeal, one need only look at a list of possible readings: there have been almost as many interpretations as there have been films. In short, Dracula, as the archetypal vampire, can be made to reflect the fears (and the desires) of every generation.

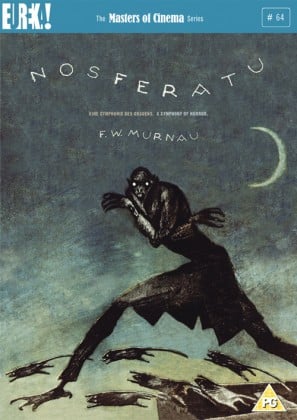

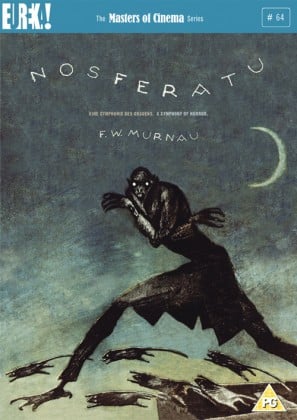

It was F.W. Murnau who, in 1922, gave the world its first great onscreen Dracula – even if, in an unsuccessful bid to escape infringing copyright, Murnau changed the Count’s name to Orlok and retitled it Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens. Stoker’s widow saw right through Murnau’s ploy and duly sued, causing the majority of prints to be destroyed. Luckily, one survived.

Seen today, Murnau’s film has lost none of its power. Murnau shot much of Nosferatu on location, adding a contrasting sense of realism to the film’s expressionistic tropes, thereby creating an ominous, otherworldly foreboding. Right at the start we read that this is ‘a chronicle of the plague of Great Death’: unlike Dracula’s victims, Orlok’s do not become vampires – they die, and Orlok is their death. Murnau strips Stoker’s text of its erotic and religious force: here, Orlok is a metaphysical harbinger of death, an unstoppable force of nature. German cinema of this period is famous for its detailed mise-en-scène, and Nosferatu is no exception, but the film also makes startling use of montage. Not only does Murnau use parallel editing to increase tension, but the moment in which Ellen awakes as Orlok feeds on Hutter, their disparate locations joined together in a single eye-line match, is truly breath-taking filmmaking.

Stoker’s widow, frustrated by unauthorised adaptations, sold the dramatic rights for Dracula to British playwright Hamilton Deane, whose adaptation was later reworked by John L. Balderston for Broadway. It was this play, rather than Stoker’s novel, that formed the basis for Tod Browning’s stodgy 1931 Dracula, a film that never quite transcends its drawing-room mystery origins – despite begin well shot by cinematographer Karl Freund, who had worked with Murnau back in Germany. The film’s theatricality extends to its hammy, stage-derived special effects, which add little dread to the proceedings. Bela Lugosi had played the role on Broadway, and his version of Dracula remains the most iconic and influential. An invention of Deane’s, this Dracula may be a far cry from Stoker’s heavily-moustached old man, but it’s also the version that has most thoroughly penetrated public consciousness.

[youtube id=”AxE4yITfRLo” width=”600″ height=”350″]

Taking its cue from Deane and Balderston’s play, in which Lucy ‘registers attraction’ to Dracula, Browning’s film has Lucy express her fascination to Mina, who will herself later receive a midnight call from the Count – much to the chagrin of her fiancé. With his thick accent and ponderous pronunciation, Lugosi’s Dracula is every bit the outsider, readable as both the invading immigrant and the suave, sexually appealing ‘other’.

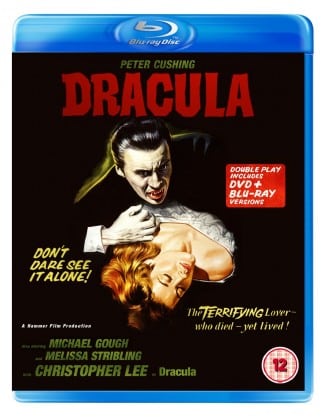

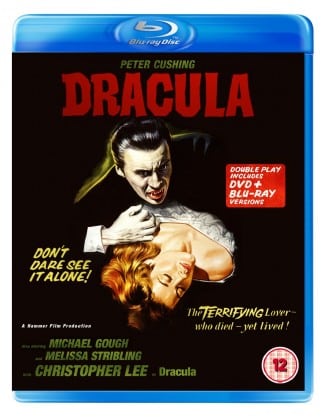

It’s the latter reading that director Terence Fisher brings to the fore in his excellent 1958 adaptation for Hammer. Here, an ill and pale Lucy excitedly removes her crucifix, opens the doors, hikes up her skirt, and lies on her bed expectantly. Dracula is no invader, but a welcome jolt of sexual energy, a manifestation of the Victorian woman’s hidden (and unfulfilled) sexual desires. We are told that the crucifix symbolises good over evil, and that Van Helsing will succeed ‘with God’s help’. Once more, Dracula is the evil other, a force of adultery who needs to be dispatched so (holy) matrimony can be resumed. If the script at times owes little to Stoker’s original narrative trajectory, the film perfectly condenses his sprawling story and captures the spirit, the dread and the disgust of the original text.

In 1979, Werner Herzog returned to Murnau’s Dracula-as-death symbolism for his dreamlike Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht. As the film’s opening images of mummified bodies help establish, this is cinema as memento mori. Lucy screams and wakes from a nightmare, but the phantom of the night is coming: death is unavoidable and cannot be escaped. A portentous dread hangs in the air, even throughout the later, joyous scenes of revelling plague victims. These scenes suggest that life can be given meaning only when placed under the shadow of death, thus rendering Dracula‘s eternal undead life both joyless and meaningless.

In the book, Mina begs the vampire hunters to feel pity for their prey, and Herzog makes this feeling manifest. Herzog’s ponderous, almost languid tone leads us to feel the profound weight of an endless life without love. Once more, the erotic undertones rise to the surface: Dracula wants love, and his lust for Lucy will ultimately be his undoing. Herzog’s vision is highly romantic, and therefore archly Gothic. Present too is the religious conflict: Lucy declares that ‘God is so far from us in the hour of distress’, and if the later use of the Host in combating Dracula seems to contradict this, it’s worth remembering the line ‘Faith is the faculty of man which enables us to believe things we know to be untrue’. There is no happy ending in Herzog’s godless universe, despite what we try to believe. Lethargic though it sometimes feels, this may well be the most philosophically rich adaptation of the material – and the one with the most monstrously mesmerising portrayal of Dracula himself.

It’s perhaps significant that Herzog returned to Murnau as his source, given that Gothic derives from a return to – and a fear of – the past. Interestingly, two other significant adaptations have likewise drawn on early cinema for inspiration: Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and Guy Maddin’s 2002 Dracula: Pages from a Virgin’s Diary. In fact, Coppola’s film seems to draw as much on past adaptations as on the novel itself, pulling in shadows from Murnau, dialogue from Browning, bloody gore and bawdy sex from Fisher, and a sense of introspection from Herzog. The film uses a glut of early cinema techniques, resulting in a breathless barrage that feels closer to baroque excess than ornate gothic purity.

Coppola seems to delight in the carnal aspects of the novel, going beyond even Fisher in his uninhibited depictions of violence and sex. In an early scene, Mina studies an explicit illustration in the Arabian Nights. She calls it ‘disgustingly awful’, but can’t take her eyes off it. Here, Dracula is an embodiment of desire and openly represents an exciting alternative to the tedium of puritanical marriage. But with this excitement comes danger: this is the age of both civilisation and syphilisation, and the women will be condemned for their promiscuous exchange of blood. Coppola mines the AIDS metaphor for all its worth, and equates the rise in decadence and sexual liberation with the end of the old (Christian) world. If the film’s excess verges at times on the ridiculous, it nonetheless remains a richly delirious and intoxicating work.

Much like Coppola, Maddin furrows cinematic history to create an erotic work of kinetic excess, but goes one further by making his film silent. His sets are skewed, stylised and symbolic, his Dracula a story of female lust and male jealousy – but also of paranoia and xenophobia (an early title card reads ‘Immigrants – others from other lands’). Dracula is a foreign invader, come to steal our wealth and our women. Maddin reminds us that Dracula ‘has the brain of a child’ and fills his lair with money stolen from England, thus emphasising the racists roots of the novel’s portrayal of the immigrant outsider. Maddin’s film, based on an adaptation by the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, makes literal the novel’s dances of death and attraction. For Maddin, Dracula’s dispatch at the hands of Lucy’s frustrated suitors serves not only as the removal of the alien body, but also as a reassertion of male dominance over female desire.

At the end of the film, the victors open the doors of Castle Dracula and walk towards the light of a new day. Inside, Dracula lies bent backwards, impaled on a phallic spike. Somehow, it seems there may still be life in him yet. After all, some things never die, and Dracula remains the King of the Undead. AB

NOSFERATU THE VAMPYRE (RE-MASTERED) AND NOSFERATU: A SYMPHONY OF HORRORS (HD RESTORATION) IS AVAILABLE COURTESY OF EUREKA, as is NOSERATU THE VAMPYRE

HAMMER’S RE-RELEASE OF DRACULA IS AVAILABLE ON DVD