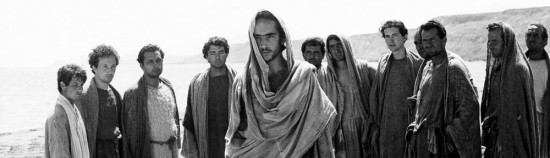

Dir: Robert Rossellini | Wri: Roberto Rossellini, Vitaliano Brancati | Cast: Ingrid Bergman, George Sanders, Maria Mauban | Drama, Italy/France, 86

In this groundbreaking film it is almost impossible to take your eyes off Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders as they enact the fading love story of a well-healed fifties middle class couple both undergoing painful heartache of their own, behind the scenes. Roberto Rossellini’s drama is the culminating masterpiece of Italian neo-realism and arguably one of the greatest neo-realist love stories of the era.

Inspiring and ushering in the New Wave, Viaggio channels the ideals of the neo-realist movement in the use of non-professional actors and rural everyday life, in the this case in Naples and Pompeii and although it performed badly at the Box Office, it went down very well with French critics, based loosely, as it was, on Colette’s novel Duo and Francois Truffaut, called it the first ‘modern film’.

The film’s plot is simple: an unhappily married couple drive down to Italy to organise the sale of an inherited villa in one of the most scenic locations in the South, the bay of Naples. They bicker and neither is at peace. Katherine is young and vivacious but disappointed with her hostile husband, Alex, who – she claims – cares only for money and work and dislikes the area: “I’ve never seen noise and boredom go so well together.” As the trip grows more complex with delays in the property sale so Alex takes it out on his wife, who harks back to a previous lover and starts to sense that divorce is inevitable. The two flirt openly with outsiders on every social occasion and spend increasing time away from each other during in activities and venues that seem to enhance their feelings of desperation and sadness. Katherine visits a morbid catacomb, Alex becomes close to a girl he meets through friends. The final moments are unforgettable, unexpected and transcendent in the history of Italian cinema and mark Viaggio in Italia out as a significant film that has stays in the memory long after the titles fade.

The production was not without it difficulties. Ingrid Bergman’s marriage to Rosellini was under severe pressure. George Sanders was at the end of his union with Zsa Zsa Gabor and was fraught from his attempts to contact her long-distance. He was not only annoyed that he was expected to improvise, but also that the director himself appeared to be making it up as he went along.

According to Tag Gallagher (The Adventures of Robert Rossellini, New York Da Capo Press, 1998) Sanders was waiting in his hotel reception as instructed at 2pm: “I was led like a man in Sing Sing’s Death House to the waiting car which whisked me away to some Neapolitan back street where Rossellini had set up the camera to shoot the momentous scene for which we had all been waiting so patiently. He had his scarlet racing Ferrari with him (a new one!) and he kept eyeing it and stroking it while the cameraman was fiddling with the lights, getting the scene ready. Finally when all was ready, Rossellini changed his mind about shooting the scene and dismissed the thunderstruck company. While we watched him in stupefied silence, he put on his crash helmet, climbed into the Ferrari, gunned his motor and disappeared with a rorar and screeching tyres round the bend of the street and out of our lives for two whole days…). Meanwhile Ingrid Bergman was equally distraught. She couldn’t improvise, she hated to improvise, which Roberto well knew. Yet whenever she’d ask what she was supposed to say, he’d snap: “Say what’s on your mind”.

After a long and tortuous process, the film was finally released in July 1954. Despite all the set-backs and unpleasantness and Rossellini’s wasteful and unorthodox methods the film emerged as one of the most enduring examples of ingenious innovation and timeless inspiration. Rossellini managed finally to get convincing performances from two people authentically portraying the end of love. MT

After a long and tortuous process, the film was finally released in July 1954. Despite all the set-backs and unpleasantness and Rossellini’s wasteful and unorthodox methods the film emerged as one of the most enduring examples of ingenious innovation and timeless inspiration. Rossellini managed finally to get convincing performances from two people authentically portraying the end of love. MT

Recently restored l’Imagine Ritrovata VIAGGIO IN ITALIA | BFI Player