Dir/Wri: Kornél Mundruczó | Cast: Zsofia Psotta, Sandor Zsoter, Lili Horvath, Szabolcs Thuroczy, Lili Momori, Gergely Banki, Karoly Ascher | 119min Drama/Thriller Hungary

Hungarian director, Kornél Mundruczó’s art house thriller is also a revenge flick with a touch of the “Pied Piper of Hamlin’ about it. Serving as an elusive parable on human supremacy, it scratches the edges of fantasy with some bizarre and brutal elements.

Dogs, or more correctly, mutts are the stars of the story which opens with a little girl cycling through the mysteriously empty streets of Budapest, followed by a pack of barking beasts. With is canine cast of Alsations to Labradors, Rottweilers and even little terriers, WHITE GOD also brings to mind The Incredible Journey with a darkly sinister twist. Is she escaping a virus, or a human enemy?

These dogs are clearly well-trained and credit goes to the Mundruczo for his ambitious undertaking, but then Magyars have a reputation for their horsemanship and this clearly extends to the canine species. It transpires that Lilli (Zsofia Psotta) the girl on the bike, has adopted a large street dog called Hagen. Lilli’s mum is off on a business trip with her new boyfriend, leaving her in the care of her emotionally distant but rather sensitive father who ironically works as an abattoir inspector.

Their relationship is not a close one and Lilli becomes even more distant from him when he insists on her getting rid of her loveable pet. Budapest is a city full of street dogs and the Hungarians appear to be a great deal less keen on animal welfare than most European countries. Hagen is soon picked up by a new owner, an unscrupulous dog fighter, who sets about turning him into a savage warrior-dog, before he escapes and ends up in the Police dog pound, where he stages a mass canine uprising. The transformation is both sad and frightening but there are also poignant moments as Hagen as his ‘mate,’ a sweet Jack Russell, desperately try to evade re-capture by their enemies – human beings. And it is this balance of power that underpins Mundruczó’s unique drama transforming it from an animal adventure to a satire with universal appeal. WHITE DOG is quite literally, a tale of the ‘underdog’ rising up and claiming his rightful place in society: on a more sinister level it could represent the masses over-taking society. A captivating and provocative piece of filmmaking. MT

NOW ON BFI PLAYER | Dedicated to the late Miklós Jancsó, WHITE GOD won PRIX UN CERTAIN REGARD in Cannes 2014.

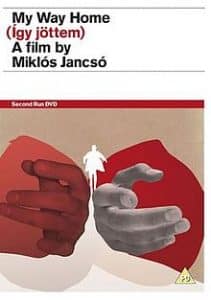

MY WAY HOME | Dir.: Miklos Jansco; Cast: Sergei Nikomenko, Andras Kozak; Hungary 1964, 108 min.

MY WAY HOME | Dir.: Miklos Jansco; Cast: Sergei Nikomenko, Andras Kozak; Hungary 1964, 108 min.