Dir/scr: Toshihiko Tanaka. Japan, drama 189′

Rei is a kanji character that can represent a variety of meanings. The genderless name is therefore a really good title for this complex but rather overlong (at over three hours) feature debut from Toshihiko Tanaka which won the Tiger prize at this year’s 53rd Rotterdam Film Festival.

Rei is about Matsushita Hikari, a self-contained thirty-something woman whose comparatively uncomplicated life in the corporate world contrasts with the trials and tribulations of her friends in a series of interconnecting dramas that highlight – albeit reductively – Japanese attitudes towards disability and, in particular, those with special needs and heightened sensibility. On a deeper level Tanaka also explores human connectedness along the lines of that well-worn phrase: “No man is an island”: It’s only through knowing each other that we really come to understand ourselves.

We first meet Hikari (Takara Suzuki) and her deaf landscape photographer friend Masato (played by Tanaka himself) in the wintery countryside surrounding Tokyo. Hikari’s life lacks a certain excitement and she seeks this out in creative scenarios. Hikari is also drawn to an actor called Mitsuru (Keita Katsumata) who she meets through her love of theatre and through a flyer where she has discovered Masato’s work. Finding his artistry compelling she asks him to take her portrait in the snowy setting. Another friend of hers Asami (Maeko Oyama) has a three-year-old daughter with special needs. Asami is dealing with the additional pressures of a husband who is having an affair with a nurse (who also cared for Masato’s mother).

Hikari is fascinated by Masato and the two share exchanges on SMS and email to get over the communication barrier. Asami is so impressed by Masato’s portraits of Hikari she commissions him to photograph her own family and these extraordinary pictures capture something that words can never do about the state of her relationship with her husband. But despite his unique and arcane talents Masato is sadly seen as a flawed character due to his hearing issues in this dense narrative in a drama that marks Toshihiko Tanaka out as a rising star in the film firmament. @MeredithTaylor

ROTTERDAM FILM FESTIVAL 2024 | TIGER PRIZE 2024

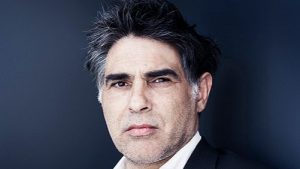

There is no filmmaker like Edgar Pêra (b.1960). His work may be an acquired taste but it is always inventive and Avant-garde referencing his heroes in creative ways and keeping the past alive. The Portuguese auteur often pays tribute to Dziga Vertov, Branquinho da Fonseca and Fernando Pessoa – but always in an ingenious way – transforming their ideas into bizarre and refreshing features, some will screen in a retrospective at the

There is no filmmaker like Edgar Pêra (b.1960). His work may be an acquired taste but it is always inventive and Avant-garde referencing his heroes in creative ways and keeping the past alive. The Portuguese auteur often pays tribute to Dziga Vertov, Branquinho da Fonseca and Fernando Pessoa – but always in an ingenious way – transforming their ideas into bizarre and refreshing features, some will screen in a retrospective at the  Edgar Henrique Clemente Pêra first studied psychology, but soon realised his vocation in Film at the Portuguese National Conservatory, currently

Edgar Henrique Clemente Pêra first studied psychology, but soon realised his vocation in Film at the Portuguese National Conservatory, currently

Dir: Malene Choi | Writer: Sissel Dalsgaard Thomsen | With Thomas Hwan, Karoline Sofie Lee | Doc | Denmark | 85′

Dir: Malene Choi | Writer: Sissel Dalsgaard Thomsen | With Thomas Hwan, Karoline Sofie Lee | Doc | Denmark | 85′