Matthew Turner caught up with Charlie Siskel to chat about an amazing discovery which led to his latest documentary

Matthew Turner caught up with Charlie Siskel to chat about an amazing discovery which led to his latest documentary

Matthew Turner (MJT): How did the project come about, first of all?

Charlie Siskel (CS): Well, John Maloof made the discovery of Vivian’s work and eventually he mounted a show of her photographs in Chicago and that was reported on by local media and I heard about the story at the time, but there was no documentary yet. That didn’t come until later. And John decided that he wanted to tell this incredible story of a nanny who happened to also be a photographer and certainly took all these photographs. But John was a real estate agent at the time and he was working on a book about the neighbourhood in Chicago, that’s why he acquired the photographs, a bunch of old photographs of the city. But he thought this would make a great documentary and he got in touch with me and not only did he have over 100,000 photographs, but I learned that there were also hours and hours of Super 8 footage that Vivian had shot and then hours and hours of audio recordings that she made as well. And I thought all of that material could be used to tell a really compelling story, which was kind of a detective story, trying to find out who this person was, how she was able to take all these incredible photos while leading what seemed to be a double life. And it was kind of a mystery and then it could be a future documentary. I don’t know, but I think, at the time, maybe they had humbler ambitions for the film, maybe it could be on TV, on public television in the States, something like that, but I thought it could be a really great feature and play in movie theatres where audiences would go and see it with other people and it would be kind of a rollercoaster ride of a story, if we did it right.

MJT: What was the process of sorting through the footage like?

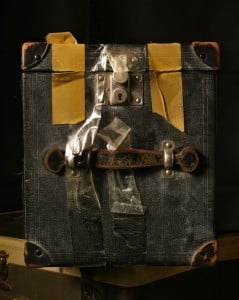

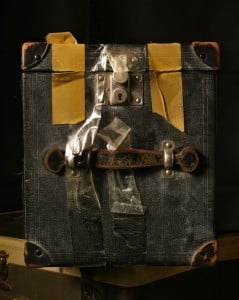

CS: Well, we had not only all the photos, but also the Super 8 recordings and the audio to go through and then a mountain of material, all this personal stuff that she had collected – articles, news article clippings and mountains of business cards and receipts from places where she bought books and thrift store jewellery that she had acquired and all of these were clues to help us construct a picture of this person, it helped us track down people who knew her in the first place and of course all of those people knew her as a nanny, not as a photographer, so here we were, piecing together a story of this brilliant artist, but no-one knew her as an artist, they knew her as the nanny and the hired help. So we started to do interviews with these people and, of course, they described her as incredibly private – maybe that’s not so surprising, given that she was the baby-sitter, you know, or a maid in some cases, and maybe she wasn’t sharing the most intimate details of her past or her life with her bosses. So that was kind of fascinating, here we were, telling a person’s story, but we were telling it through maybe, in some ways, unreliable narrators, you know? And they gave us a picture of Vivian that was only a partial picture, so we were finding contradictions between what they were saying, some of them described her as having a fake accent, they thought that her accent was fake and someone else thought that her accent was real. And people had strong opinions about Vivian – very strong opinions – and they were conflicting opinions, so we kind of created a portrait of her where the audience has to kind of solve the riddle along with us and judge for themselves who they believe, what they think of the testimony that they’re hearing from these witnesses. They kind of have to act like a jury and judge for themselves.

MJT: I thought the contradictions were really interesting. What was the biggest surprise you discovered? Something that you didn’t know before the filming started?

CS: Well, of course, learning that there were stories about abuse, that at least one person in the film described more abusive behaviour – that was a shock, it was troubling to hear that and it caused a lot of debate for us, a lot of soul-searching, I would say, about how that fit into the story that we were telling and we wrestled with how to treat it in the film. That was the only story that we heard that was an extreme, but there were others that we include in the film that were also troubling that involved Vivian mistreating the kids and some of the kids had some negative memories of her, so suddenly we recognised that our subject, as brilliant an artist as she was, was not a saint and that humanised Vivian further for us, making us realise that this was not going to be an easy task of painting a one-sided picture, we really needed to embrace the complexity of the story and the complexity of trying to make a film about a real, dimensional human being. That was a big surprise and a challenging one, but I think the biggest revelation in making the film was to start out thinking that we were telling the story of a nanny who happened to take a bunch of incredible photographs, almost just by accident or something, and really realising, as we were making the film, that that wasn’t the story at all, that this was a story of a true artist – who Vivian really was was a brilliant artist, that was her true identity, I think nanny was really more of an after-thought. Being a nanny was kind of a means to an end, almost a form of camouflage, even a masquerade, I would say, because sometimes she was literally taking the kids on these field trips, from the wealthy suburbs of Chicago, these very comfortable surroundings, into the grittiest parts of the city, to the slaughterhouses, to Skid Row, to the slums, and you’ve got to wonder, was she taking them on these adventures to broaden their horizons or was she taking them there because she knows that’s where she’s going to get her best photographs? So maybe it’s a little of both, I don’t know, but I imagine the kids just wanted to go to the zoo [laughs], but they ended up going to the worst parts of town.

MJT: How easy was it to track down all the people that knew her and how willing were they to get involved?

CS: Some easier than others. Once the story got out, some people actually sought us out and contacted us and others were much harder to find. And really pouring through endless documents and shreds of paper and crumpled-up business cards and looking through, almost like an archaeological dig, and that’s kind of the metaphor we used for laying out all of her paper, her belongings, the way an archaeologist creates a grid for sifting through a site where there are dinosaur bones, to create order out of chaos. And so sometimes we would find a business card that would yield a great subject, a great interviewee and also, one family would lead to the next family and we would find people that way. And then the receipts would lead us to stores that she frequented and we found subjects that way. We contacted over ninety different people who knew Vivian, we did not end up interviewing all of them, mostly because we would kind of talk to them on the phone a bit before we would sit down and do an interview and if we found that they had little to say or that what they had to say, we already had many other people telling similar stories, or that side of her, then we didn’t feel the need to double up, in that sense. And so we ended up interviewing about forty or so people and out of that, not all of them are in the film, because even with whittling down to that many subjects, we felt that we had it covered through the people that we ended up including in the film, more than twenty-five people. So that was that selection process and then there are people who did not appear in the film.

MJT: Was there anyone that said no?

CS: At the end of the film, we talk about the family that paid for her apartment and they are the family that are seen early on in the film, there’s Super 8 footage of the children that she took care of, and another person in the film talks about that family. That’s a family named the Gettenbergs – we actually did do an interview with them, but they asked us not to include it, ultimately, in the film, they just felt that by the time – given that the film took more than three and a half years to make – when we first started, they were the first family that we contacted, but they were approached and interviewed by so many other journalists. They didn’t really hide their identities – in fact, the opposite, when there were journalists that wanted to talk about Vivian Maier – this was early on and even before I got involved in the project, John was quite happy to share the information about the people who knew Vivian, because he was interested in getting her story out and having people see her work. I mean, that was why he mounted the show of her work in the first place. And many families came to that show at the Cultural Centre in Chicago and when some of them learned for the first time that she had taken all these incredible photographs – of course, they knew she had a camera, but they didn’t know where she was going or what kind of images she was taking – and they were seeing the photographs, certainly, for the first time and they were happy to talk to reporters early on. But they, over time, got so tired of the phone call and the coverage that they just asked not to be in the film and we respected that request.

MJT: Do you have a favourite moment in the film?

CS: I have many favourite moments. I love watching the scene where the two men debate Vivian’s accent. It always gets a lot of laughs and there are a lot of funny moments in the film, because Vivian herself was funny and the story, with all of its mystery, is also a funny one. I think, in some ways, Vivian was having a bit of a laugh at all of this, in her own way. She describes herself as a mystery woman in the film and she describes herself as a spy, but I think she does that with a wink and a twinkle in her eye. And in the film, when she calls herself a mystery woman, there’s audio of her saying that to these kids and the kids laugh, because, of course, it was Vivian being funny about her mystique and about her sense of mystery, but I love the debate over her accent because I think it’s funny on some level, but the kind of mental gymnastics that people have done to try to figure Vivian out and to try to get her right and there is something funny and entertaining about this whole endeavour, to pin down Vivian and try to understand her. And because I think, maybe, in the end, the answer isn’t all that complicated – she was a brilliant, brilliant artist and I don’t think she hid her art for some romantic reason, as some have suggested, she kept her art secret because she wanted to create art only for herself and art for art’s sake, that she was somehow too good for publicity, she was too good for the public and her art would be tainted by public view, that’s something that people have suggested. I think the truth is probably much more mundane – I think she probably didn’t show her work because it’s expensive to print it, it’s logistically complex to put together all the resources to do it. And she did, at times, make an effort, we show one such time in the film when she tried to get her work printed in France and that was a bit of a hare-brained idea, the notion that she would have to send her work halfway around the world to a tiny village in France, when here she is in New York or Chicago, places where she could have found very, very good printers, probably really good ones. And so maybe that was a bit of a self-defeating idea that she had and certainly many artists don’t share their work, don’t find a way to publicise their work, some of them are incredibly publicity shy, aren’t good business people, fear rejection as any artist does. So I think these are the reasons why we don’t see much of the great art that’s produced – I think the fact that Vivian’s work has been found makes her an exception. The rule is probably that most great works of art are lost.

MJT: Why do you think she left so many of her photographs undeveloped?

CS: Again, as I say, in addition to all of the things that I’ve mentioned, the cost, the time, the work involved, I think she also fell into a pattern after years and years of operating in this way where she even stops having the rolls of film developed. I think she fell into a pattern – she could print some of her work, a very small amount, relative to the amount of photographs that she took, and the postcards that she had made with the printer in France, it looks like she may have had a side business at one point, trying to sell postcards. But obviously most of her work, and the great, iconic images that we see today, she didn’t share, but I think mostly it was that, over time, she settled into a pattern of ‘Maybe one day I’ll have this work developed, printed, etc, but not today’. And not this year. And not this decade. But what’s incredible is that in spite of all of those challenges, both external obstacles and internal ones, she never stopped doing the work, she never stopped taking the photographs and that is a real lesson for any artist and the real heroism of her life is that she continued to do the work, year after year, decade after decade. And to me, that story is not a fairy tale story, like the idea of Vivian secretly creating work only for herself, but it’s a much more heroic one, it’s one that I think we can all relate to, which is, ‘Oh, being an artist is actually a lot of work’. If you want to be a great writer, you have to write. If you want to be a great photographer, you have to take pictures. If you want to be a great painter, you have to paint. The idea of Vivian saying to herself in the 1950s, ‘You know what I think I’ll do? I think I’ll take over 100,000 photographs, but I’m only going to do that for myself, it’s going to be private and I’ll do this for the next 50 years’, to me, that strikes me as implausible, nothing I can relate to as a human being.

MJT: I was just wondering if you had seen Eric Steel’s film, Kiss the Water, about Megan Boyd, who was a similarly reclusive character? Her trade was fly-tying for anglers rather than photography, but it strikes me the film would make a good companion piece.

CS: I have never seen it, but I will seek it out!

MJT: What’s your next project?

CS: I don’t know – I’m always looking for another story, but this will be hard to match. This is a story I think about every day, I’m inspired by Vivian’s example as an artist and I continue to grapple with the scenes in the movie myself and I’ve really enjoyed sharing it with an audience, both in the US and abroad, because people are having the same kind of sense of discovery that I know John had when he first found Vivian’s work and certainly the same reaction that I had when I first got involved. It’s just the more you know, the more you want to know and the more you look at her photos, the more you want to see. So it sets a very high bar, certainly, for whatever’s next.

FINDING VIVIAN MAIER IS ON GENERAL RELEASE FROM 18TH JULY 2014

[youtube id=”saHvubuWB-0″ width=”600″ height=”350″]