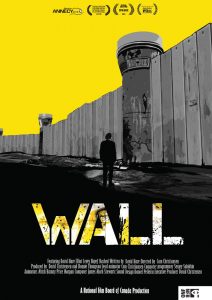

Dir.: Cam Christiansen; Documentary/Animation with David Hare, Elliot Levey, Nayef Rashad; Canada 2017, 82 min.

Dir.: Cam Christiansen; Documentary/Animation with David Hare, Elliot Levey, Nayef Rashad; Canada 2017, 82 min.

When Canadian producer David Christensen listened to David Hare’a 2009 Podcast Wall, a monologue about Israel building a wall between them and Palestine, he knew that animator Cam Christiansen would be the right person to tackle the project. The result, a mixture of 3D motion capture technology, documentary and hand drawn animation, is an aesthetically stunning portrait of the 708 km long wall, so far amounting to 4 Billion US dollars since building began in 2002. The political and human cost cannot be put into figures, and Hare’s script does not always allow us to come to terms with the numerous contradictions.

Hare, who wore a Lycra suit for his first outing as an actor at the Pinewood Studios where the motion-capture footage was shot; is – symbolically – accompanied by the English/Israeli actor Elliot Levey and his Palestinian counterpart Nayef Rashad. Levey wants to stage a co-operation, something Palestinians are not fond of, because it would legitimise the status quo between Israel and Palestine. Hare visits the Israeli novelist David Grossman, who is critical of his state’s policies, but admits that there must be a place where Jews feel safe. Driving along the monstrous wall from Jerusalem to Ramallah and Nablus, we see the damage the continuous war has done. Nablus, once the trading centre of Palestine, is a ghost city. The most famous cafe, where guests once fought for one of the 500 places, is a ghostly place where Hare and his friends are the only customers. Ramallah, the seat of the Palestinian administration has had better luck: mainly because it is one of the few places not mentioned in the scriptures of the main religions in the area. We learn that Hamas is not popular, they have won elections because the PLO is totally corrupt. Then there is the story of a man who has worked as in informer for the Israelis. Hamas, imprisoning him, then invented an innovative form of torture: on the wall of the cell, they have drawn a picture of a bicycle, asking the prisoner to fetch it, or risk torture. The journey is always interrupted by senseless controls by the Israeli forces, whilst a parallel road, fifty years in the future, will be reserved for cars with Israeli number plates, the traffic flowing uninterrupted. And the settlements, some even unlawful under Israeli law, overlook the West Bank in a very menacing way. But, the wall has stopped eighty percent of Palestinian terror acts in Israel. At the end, the black-and-white transforms into the colourful graffiti on the wall – not unlike those on the Berlin Wall.

Whilst the aesthetics are brilliant, the political agenda is questionable – but perhaps, this is only to be expected. Nearly seventy years of permanent war has destroyed any kind of hope. For Israel, this means the most powerful military force in the region has no influence on the state of mind of its citizens: Grossman mentions that most Israelis feel vey insecure. Perhaps the repressed diaspora thinking has returned, but whatever the arguments on both sides, the founding father of Israel, Theodor Herzl, did not envisage a Sparta in the desert. AS

WALL opens MARCH 1st | BERTHA DOCHOUSE | 6pm screening Q&A |Cam Christiansen