Dir.: Sebastian Marnier; Cast: Laurent Lafitte, Emmanuelle Bercot, Luana Bajrami, Victor Bonnel; France 2018, 103 min.

Sebastian Marnier follows his debut Irreproachable with an impressive adaption of Christophe Dufosse’s novel of the same name. Set in a posh secondary school, it has very much in common with John Wyndham’s novel The Midwich Cuckoos, filmed twice as Village of the Dammed in 1960 and 1996.

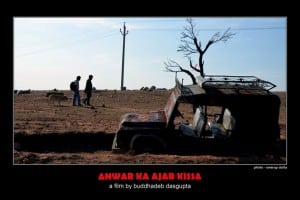

Supply teacher Pierre Hoffman (Lafitte) is called to St. Joseph’s College, after his predecessor, Capadis, jumped out of the window during a lesson. Hoffman is soon confronted by a group of six very gifted students who have formed a secret society led by Apoline (Bajrami) and Dimitri (Bonnel). This lot don’t seem concerned about what happened to Capadis; they regularly meet in a disused quarry. to perform daring acts and beat each other up – they seem to be immune to pain. Apoline accuses Hoffman, who is gay, of fancying Dmitri. But this is really to get rid of Hoffman on the grounds of his collection of video tapes recording the group’s activities. One of Hoffman’s fellow teachers, a music instructor and choir mistress called Catherine (Bercot), seems to be the only teacher that understands the group. It emerges that her family were killed in a car accident, while she was driving. Dimitri and his group invade Hoffman’s privacy in revenge for him snooping on them. After the finals, the six hijack a bus in a bid to crash it into the quarry. Hoffman escapes by the skin of his teeth, but the stunning finale gives answers to the many questions which have piled up.

Shot by DoP Romain Carcanada, the visuals have a glacial quality, as if everything was set in a frozen climate, despite the stifling summer heat. But this seems to mimic the icy coolness of the group of six. Hoffman is shown as a tortured soul, detached and lacking in any real identity. Bajrami and Bonnel lead with a maturity well beyond their age in this tense and gripping thriller. AS

SCREENING DURING LONDON FILM FESTIVAL 2018 | 10-21 OCTOBER 2018