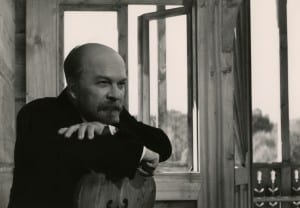

Born in 1939 in Warsaw, Poland, Krzysztof Zanussi is s documentary and feature film director. He studied Physics and Philosophy at University and graduated from Lodz Film Academy in 1966. Member of the jury at the Venice Film Festival in 1981. Member of the jury at the Sundance Film Festival in 1986.

We recently talked to Krzysztof whose latest film FOREIGN BODY was released in 2015. A retrospective of his films is currently showing on MUBI.

F Let me first say how much I enjoyed ILLUMINATION (1973) I take it you didn’t have any issues with the censors on this film?

KZ Oh, but yes I did. There was a whole scene cut from it. In the original film, there was a scene of university demonstrations, from 1968, where the students demonstrated in support of their tutors. I wrote it in and got it past the script censor, because it is easy to disguise things in a script, but then the film is screened in the Ministry of Culture too and then they make cuts. There still remains a still (photograph) of Retman demonstrating in the final film, which I argued to keep and anyone who knew those times would understand the context when they view the film.

F I understand ILLUMINATION isn’t autobiographical(?) but you were filming about things you knew about.. studying Physics as you did..

KZ Yes, my life is very different, the film does not reflect what was happening to me at all, but of course I knew Physics.. you meet a partner…

KZ Yes, my life is very different, the film does not reflect what was happening to me at all, but of course I knew Physics.. you meet a partner…

F Why did you study Physics?

KZ I studied Physics, as in fact the lead character Retman states in the film ILLUMINATION, because I felt I wanted something that was certain in life. Then I moved over to Biology, as many of us did then.. I did get interested in Genetics, right back then, at the start of things and could already see the great good it might potentially do, but also of course, the great bad too. My father used to say to me ‘don’t believe anything any tutor tells you, except the Maths and the Physics teacher’. I like Biology …and many other subjects, but they are all supposition and opinion.

F You have a very interesting look to ILLUMINATION your DoP was very good…

KZ: Yes, yes (Edward Klosinski); he was wonderful. He also shot The Promised Land. He passed away recently (2008).

F Wonderful film. Starts out like a Chekov play and then just opens out to something massive. You met at film school?

KZ Yes, we studied together.

F And the style.. it appears to me that you were juxtaposing a cinéma verité with a highly stylized form: something quite revolutionary then

KZ Yes, I had been very influenced by the French New Wave… I wanted a documentary feel for some of it; to make it feel real.

F And what did you shoot on?

KZ: 16mm blown up to 35mm. We always shot 16mm as it was much cheaper. We had access to Kodak Eastman stock, which we loved. We felt very lucky. With only a very limited ratio. We only had enough (film) for 1 or 2 takes, so if nothing went drastically wrong, you moved on.

F This must have been good for the actors.. focussing them too when there was a take..?

KZ: Well, of course the actors knew this was always the case, so… (they were used to it). One time I was working with a famous French actress and we did a couple of takes and we were moving on and she said ‘was that ok’? And I said ‘yes, of course’, because she wasn’t convinced… she had stumbled over a line, but she soon learnt how it was to film in Poland!

F: Also in the “Martin Scorsese Selects” strand, tell us about CAMOUFLAGE. How do you see this film in hindsight?

F: Also in the “Martin Scorsese Selects” strand, tell us about CAMOUFLAGE. How do you see this film in hindsight?

K.Z.: Well, CAMOUFLAGE is one of the about forty films I have directed, and they are all my dear children. And I can say, that I have not any favourites. But CAMOUFLAGE had a very strong resonance from the audience when it was shown, almost forty years ago. And today, I am told by the audience, that it has not lost any of its actuality. And I did hoped so much, that this would not be the case. But when I was young, I was more optimistic, I thought that opportunism and corruption were just part of this particular system we lived in, but now I know better.

F: Yes, one tends to blame the system for what is, unfortunately, human nature. What about THE CONSTANT FACTOR, from about in the same period, the two films only three years apart.

K.Z.: It is somehow the same topic, about an idealistic man, in a corrupt society, who tries to preserve his ideals. Which is very difficult, if you are not a hypocrite. Later on in life, I revised my ideas about this topic, and made a sort of sequel to the old film, five years ago, Revisited, even with some of the old actors. And I thought, I was much too hard in my judgement in CONSTANT FACTOR, not about the main character, but the people caught in the system. Because now, I can, see that the main character in the old film, which whom I identified at the time, is quite inhuman. He loves ideals, but not humans. Today I would be more tolerant towards human weaknesses. If I could speak for this main character in THE CONSTANT FACTOR, I would say now ‘sorry’ to my colleagues, I was too tough on you.

K.Z.: It is somehow the same topic, about an idealistic man, in a corrupt society, who tries to preserve his ideals. Which is very difficult, if you are not a hypocrite. Later on in life, I revised my ideas about this topic, and made a sort of sequel to the old film, five years ago, Revisited, even with some of the old actors. And I thought, I was much too hard in my judgement in CONSTANT FACTOR, not about the main character, but the people caught in the system. Because now, I can, see that the main character in the old film, which whom I identified at the time, is quite inhuman. He loves ideals, but not humans. Today I would be more tolerant towards human weaknesses. If I could speak for this main character in THE CONSTANT FACTOR, I would say now ‘sorry’ to my colleagues, I was too tough on you.

F So, going back, you studied Physics and then you went to Film School…

KZ I went to film school for three years and then they threw me out..

F How long is the course?

KZ Five years. But you see I was studying the Nouvelle Vague, I was on set with Claude Chabrol, Jacques Truffaut… seeing, learning from them how they made films… very fluid, without camera set ups and improvising with actors. Completely different from how we were taught at school. So I came back to film school and made my end of year film using these Nouvelle Vague methods before anyone.. my tutors.. knew what Nouvelle Vague was! So of course they failed me.

F Because you hadn’t used ‘correct’ camera set-ups and lighting and stuff?

KZ Exactly..

F So what did you do?

KZ Oh, well I had to take the year again effectively. And I understood I just had to make a film in the style my tutor wanted and I passed.

F I’m interested in what influenced you.. You were born at the start of the war.. do you remember much about it? Did it have an impact on you?

KZ Well, I of course made a few films about the war but not many..

F Yes, but I mean personally, did it affect you?

KZ Yes. Very much. I think. I remember walking down the street and the person walking next to me being shot dead and just carrying on walking, knowing that person was dead and would be buried in a few hours. You always remember these things. But the death of animals had a bigger impact than the death of humans.

F What do you mean?

KZ I saw a horse hit by napalm. On fire and you couldn’t tell what was… And a dog.. we were passing by this tall building and there was a fire on the first floor, but up on the fifth floor, on the balcony was a dog and I knew the dog was going to die. That no one was going to put the fire out.

F So, even though you didn’t actually see it happen, see it die, the knowledge that this dog would die in an hour or so..

KZ Yes, exactly. It made a big impact on me.

F What inspires you to make films? You must have been asked this question many times over the years.

KZ Many times.. yes and I have stock answer… but.. Fear. Fear is a great motivator.

F Fear of what?

KZ Fear of many things. Of being lonely… of not connecting with people. I mean, you wouldn’t be sitting here, we wouldn’t be talking, if it wasn’t for the fact that I have made films.

F True..

KZ Fear of not achieving anything. It stopped me being stuck in myself; Got me out there and allowed me to test my version of humanity and ask others whether they saw or felt the same things. How others receive a film is always different.

F Because people bring with them their own filter, their own baggage through which they view the film. When you make a film, it becomes something else, something separate to you, that somehow belongs to others too. You have to let it go.

KZ Exactly. And it is notable sometimes with different countries how they perceive a film. I had a retrospective in Thailand and there the metaphysical aspects of the characters problems didn’t interest the audience at all, but his situation was everything. They related to that, but not at all to the other. But you can’t tell them what your film is about.

F Where else have you been with your films?

KZ Not much to the US or China or Russia, but I went to Cuba. I met Fidel Castro with ILLUMINATION.

KZ Not much to the US or China or Russia, but I went to Cuba. I met Fidel Castro with ILLUMINATION.

F Oh wow. How did that come about?

KZ; Well, they wanted to show the film out there, but it needed to be passed by Castro first, before it could be shown and he didn’t have a screen up at his house, so he came down to see it and I was banned- everybody was banned from being in there, except a few close people, but I spoke a little Spanish, so when I knew there was going to be this screening, I just went along and told them I was invited as the filmmaker and no one could say anything, so they of course let me in, so I sat down and then the worst nightmare of any director happened; Just a few minutes in and the projector broke down, the film broke..

F It just snapped…?

KZ Yes, so the lights come up and Fidel sees me and he is very angry and wants to know what I’m doing there… So I ask him what he thinks of the film and he says he doesn’t like it much, but we talk and he agrees to see some more, so they fix it and he watches some more and then he sees it all the way through to the end.

F And..?

KZ Well, he still doesn’t like it and he cannot understand how the Politburo in Poland has allowed me to make it, but he likes that it is about science… about Physics. So, he decides to let them screen the film, in the hope that it might persuade people to study science.

F That’s amazing. So.. he’s quite open-minded then, to allow it, even though he didn’t like it…

KZ Well, I think he is more just a pragmatist.

F Do you have a favourite film?

KZ Ah. No. it isn’t fair. All films are like your children and you love them all.

F: In 1982 you won the “Golden Lion” in Venice for A YEAR OF THE QUIET SUN. This film seems somehow forgotten today.

K.Z.: I don’t know. It had a very good run in the United States, but it might not have been so extensively shown in Great Britain. But A Year of the Quiet Sun is one of my dearest films.

F.: You stated in an interview, that when you were a producer at “Tor” Studios in the 1980s, you had, despite the censors, a partial autonomy. How come?

K.Z.: Yes, from 1956 onwards, this is true. Before that, we had the Marxist system really implemented one hundred percentage. But that system was falling apart, it was really brutal. But afterwards it became more tolerant, lenient and flexible.

F.: So, as an artist, where did you think you had the greater freedom, under the communist system or the capitalist one?

K.Z.: (laughs) You should never compare one disease with another. First of all, the free market economy produces more chances for everybody. But, we have to find another way of life, because we cannot go on growing like we do. The planet will not stand for this. We will have to concentrate more on spiritual growth, than on material.

F: In 1996 you made your most autobiographical film, AT FULL GALLOP. How did it feel, revisiting your childhood?

K.Z.: I wanted to make this film much earlier, but after I wrote the first 30 pages of he script, it became clear, that this would never pass the censors. But it was very exciting, as it must be for every artist, to re-visit his youth. I had another script, about a different time of my life, which the BBC was interested in, but it came never to fruition. But coming back to At Full Gallop, it was ridiculous was happened in those early years after the war in Poland. Even horse riding was forbidden, because it was deemed to be bourgeois. You could breed horses, but riding was forbidden, because it was supposed to be repressive: the human was on top of the horse.

F: Your newest film, FOREIGN BODY, which was premiered in 2014, caused quite a commotion. Why?

K.Z.: Well, I never thought I could be so angry again, I thought, in old age, I would get more tolerant. But there it is: in the old days, we were really fighting for freedom, and today the young people are selling their freedom to the corporation. What for? They are selling their souls, not their work. So, this film is the voice of anger. Because human relationships are suffering because of this attitude, people become inhuman. But there were great protests against the film, because people like to work for the corporations, and for the material freedom they gain this way. And I also made references to Judeo-Christian ethics, which are not as dried up, as some think. So, that’s the bone of contention.

F.; So you were disappointed in global capitalism?

K.Z.: No, I never had any illusions, about the perfect system. I believe that every person has a space, and he has to be as human as possible. And the fabulous rich ones do not need to be so rich, to have a human space they can live in satisfactory.

F.: Finally, a question about the ‘ordinary’ anti-Semitism in Poland. I have watched Jerzy Stuhr’s CITIZEN which I very much liked. I believe that this was the first Polish film to confront ‘ordinary’ anti-Semitism, for a very long time.

F.: Finally, a question about the ‘ordinary’ anti-Semitism in Poland. I have watched Jerzy Stuhr’s CITIZEN which I very much liked. I believe that this was the first Polish film to confront ‘ordinary’ anti-Semitism, for a very long time.

K.Z.: That is a very complex question. There are explanations, not excuses. Poland had a huge minority, nearly three million Jews, ten percentage of its population. This is incomparable with any other nation in Europe. The ugly part of anti-Semitism in Poland is that many peasants got richer because of the victims of the holocaust. This sense of guilt makes people aggressive again. You hate somebody you profited from.

F.: And the role of the Catholic Church in this question?

K.Z.: Until ten years ago, when Pope John-Paul II died, there was no anti-Semitism, but now, there are some parts of the Catholic Church, who regrettably, are indulging again in anti-Semitism.

A RETROSPECTIVE OF ZANUSSI’S FILMS ON MUBI | JANUARY – MARCH 2-18 | HIS LATEST FILM ETER IS IN POST PRODUCTION

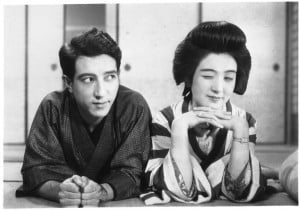

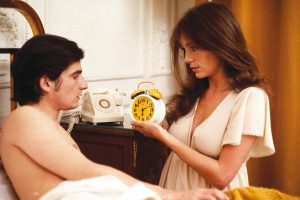

In 1966 Léaud would star in Godard’s Masculin, feminin: 15 Faits Précis, winning a Silver Bear for Best Actor at the Berlinale for his role as Paul, who is in a ménage-a-quatre with three women in a contemporary Paris. Loosely based on Maupassant’s short stories, this feature was the beginning of the break Godard would make with narrative cinema. Also called The Children of Marx and Coca Cola (an inter-title of the feature), sex and politics are at the core. Léaud is fragile, and the lighting shows him as beautiful and vulnerable as the three women, Madeleine (Chantal Goya), Catherine (Isabelle Duport) and Elisabeth (Marlene Jobert). All four main protagonists have very different plans for the future, when their agendas collide. There is immense elegance and beauty here (DoP Willy Kurant), and Godard treats his actors (perhaps for the last time) with more care than in the verbal politics of later films. Pauline Kael called it “that rare achievement: a work of grace in a contemporary setting” and for Andrew Sarris it was “the film of the season”.

In 1966 Léaud would star in Godard’s Masculin, feminin: 15 Faits Précis, winning a Silver Bear for Best Actor at the Berlinale for his role as Paul, who is in a ménage-a-quatre with three women in a contemporary Paris. Loosely based on Maupassant’s short stories, this feature was the beginning of the break Godard would make with narrative cinema. Also called The Children of Marx and Coca Cola (an inter-title of the feature), sex and politics are at the core. Léaud is fragile, and the lighting shows him as beautiful and vulnerable as the three women, Madeleine (Chantal Goya), Catherine (Isabelle Duport) and Elisabeth (Marlene Jobert). All four main protagonists have very different plans for the future, when their agendas collide. There is immense elegance and beauty here (DoP Willy Kurant), and Godard treats his actors (perhaps for the last time) with more care than in the verbal politics of later films. Pauline Kael called it “that rare achievement: a work of grace in a contemporary setting” and for Andrew Sarris it was “the film of the season”. A year later Godard would cast Léaud as part of a group in La Chinoise (1967), this time surrounded by two women and two men, but with a very much harsher political focus. Based on Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed, this was Godard’s first adventure into Maoism. Léaud is Guillaume, in love with Veronique (Anne Wiazemsky), who has a much stronger personality than him, and will finally leave him. Kirilov (Lex de Bruijin), is the weakest of the trio and he will kill himself, as in the novel. Léaud’s Guillaume is in love with Veronique, but he is very much a man of clever words, but little action. Veronique on the other hand, is much braver, and decides in the end to assassinate the Russian Cultural minister on a visit to Paris. But he mixes up the numbers of his hotel room, and kills the wrong man. Wiazemsky, the grand daughter of novelist Andrew Malraux, then the Gaullist minister for Culture, fell in love with Godard, and the couple married after the shooting. As an in-joke, Godard casts Francis Jeanson in the film (Wiazemsky’s philosophy lecturer at the Paris 10 (Nanterre) University) having a debate with Veronique while on her way to assassinate the minister.

A year later Godard would cast Léaud as part of a group in La Chinoise (1967), this time surrounded by two women and two men, but with a very much harsher political focus. Based on Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed, this was Godard’s first adventure into Maoism. Léaud is Guillaume, in love with Veronique (Anne Wiazemsky), who has a much stronger personality than him, and will finally leave him. Kirilov (Lex de Bruijin), is the weakest of the trio and he will kill himself, as in the novel. Léaud’s Guillaume is in love with Veronique, but he is very much a man of clever words, but little action. Veronique on the other hand, is much braver, and decides in the end to assassinate the Russian Cultural minister on a visit to Paris. But he mixes up the numbers of his hotel room, and kills the wrong man. Wiazemsky, the grand daughter of novelist Andrew Malraux, then the Gaullist minister for Culture, fell in love with Godard, and the couple married after the shooting. As an in-joke, Godard casts Francis Jeanson in the film (Wiazemsky’s philosophy lecturer at the Paris 10 (Nanterre) University) having a debate with Veronique while on her way to assassinate the minister. Truffaut’s 1973 outing La Nuit Americaine (Day for Night), is essentially about filmmaking, showing Léaud as the weak and self-obsessed actor Alphonse. During the filming of Je vous présente Pamela , a conventional weepie, he fancies leading lady Julie Baker (Jacqueline Bisset), who has recently had a breakdown. Out of pity she sleeps with him but Alphonse then ‘phones her analyst, Dr Nelson (David Markham), who has left his own family to live with her, and spills the beans on their fling. Léaud plays the histrionic weakling with great skill. And Truffaut, playing himself as the director, assumes the role of his protector – much as in real life. Godard, who by now had broken with his ex-friend Truffaut, called Day for Night “a big lie” – later the two founding fathers of the Nouvelle Vague fought over Léaud who somehow survived the acrimony and went on to work with another enfant terrible, Finnish director Aki Kaurismaki.

Truffaut’s 1973 outing La Nuit Americaine (Day for Night), is essentially about filmmaking, showing Léaud as the weak and self-obsessed actor Alphonse. During the filming of Je vous présente Pamela , a conventional weepie, he fancies leading lady Julie Baker (Jacqueline Bisset), who has recently had a breakdown. Out of pity she sleeps with him but Alphonse then ‘phones her analyst, Dr Nelson (David Markham), who has left his own family to live with her, and spills the beans on their fling. Léaud plays the histrionic weakling with great skill. And Truffaut, playing himself as the director, assumes the role of his protector – much as in real life. Godard, who by now had broken with his ex-friend Truffaut, called Day for Night “a big lie” – later the two founding fathers of the Nouvelle Vague fought over Léaud who somehow survived the acrimony and went on to work with another enfant terrible, Finnish director Aki Kaurismaki. I hired a Contract Killer (1990) was one of Kaurismaki’s first English language films and he made a beeline for Léaud in the lead role. The gamine actor of Day for Night had since changed dramatically. His slight, almost feminine appearance was gone, and he’d put on a substantial amount of weight – his acting too was from another dimension. He plays Henri Boulanger, an English Civil Servant, who is sacked after fifteen years of service due to privatisation. With no life outside his work, he tries – in vain – to commit suicide. Then asks a contract killer (Kenneth Colley) to step in. But Margaret (Margi Clarke) gives his life a new meaning. With time running out, Henri tries to contact the killer, to reverse the order. Léaud is totally morbid and emotionally reduced, the environment is straight out of the 1950s, the colours pale, bleached out by wear and tear. Léaud’s agile friskiness has been replaced by gentle placidness, making him look much older than forty-six. But his acting had matured too, and he slips easily into character roles nobody would have expected from him in his New Wave days. AS

I hired a Contract Killer (1990) was one of Kaurismaki’s first English language films and he made a beeline for Léaud in the lead role. The gamine actor of Day for Night had since changed dramatically. His slight, almost feminine appearance was gone, and he’d put on a substantial amount of weight – his acting too was from another dimension. He plays Henri Boulanger, an English Civil Servant, who is sacked after fifteen years of service due to privatisation. With no life outside his work, he tries – in vain – to commit suicide. Then asks a contract killer (Kenneth Colley) to step in. But Margaret (Margi Clarke) gives his life a new meaning. With time running out, Henri tries to contact the killer, to reverse the order. Léaud is totally morbid and emotionally reduced, the environment is straight out of the 1950s, the colours pale, bleached out by wear and tear. Léaud’s agile friskiness has been replaced by gentle placidness, making him look much older than forty-six. But his acting had matured too, and he slips easily into character roles nobody would have expected from him in his New Wave days. AS

Vagabond

Vagabond