The first physical film festival since Coronavirus VENICE returns to its origins with a bracingly auteurist competition line-up that shines the spotlight on Arthouse masters and brazen new talent From Europe, Asia and South America.

Championing female filmmakers and fraught with exciting news films from veterans Lav Diaz, Fred Wiseman, Andrey Konchalovsky, Orson Welles and Amos Gitai the 77th Venice Film will take place on the Lido from September 2-12.

Among the regular auteurs selected are Chloe Zhao (Nomadland), Nicole Garcia (Lovers), Michel Franco (Nuevo Orden), Kiyoshi Kurosawa (Wife Of A Spy), Malgorzata Szumowska (Never Gonna Snow Again, co-dircted by Michal Englert) and Gianfranco Rosi with his latest documentary Notturno

Buzz-worthy British films include Roger Michell’s The Duke, with Jim Broadbent and Helen Mirren; and Luke Holland documentary Final Account, both playing out of competition. The Critics’ Week selection also includes The Book of Vision starring Britain’s Charles Dance and Uberto Pasolini’s Nowhere Special starring James Norton and produced by a UK/Romania/Italian team.

The festival opens with Daniele Luchetti’s Lacci, the first Italian film to open the celebrations fr quite some time. Festival director Alberto Barbera describes it as: “an anatomy of a married couple’s problematic coexistence, as they struggle with infidelity, emotional blackmail, suffering and guilt, with an added mystery that is not revealed until the end. Supported by an outstanding cast, the film is also a sign of the promising phase in Italian cinema today, continuing the positive trend seen in recent years, which the quality of the films invited to Venice this year will surely confirm.”

Competition

Nomadland (US) (above) | Dir. Chloe Zhao

Frances McDormand (Three Billboards) embarks on a road journey across America in the latest from The Rider director Chloe Zhao

Quo Vadis, Aida? | Dir. Jasmila Zbanic

And Tomorrow The Entire World (Ger-Fr) | Dir. Julia Von Heinz

The Disciple (India) | Dir. Chaitanya Tamhane

Never Gonna Snow Again (Pol-Ger) | Dir. Malgorzata Szumowska, Michal Englert

Notturno (It-Fr-Ger) | Dir. Gianfranco Rosi

Gianfranco Rosi poignant love letter to Lampedusa (Fire at Sea) won him an armful of awards including the Golden Bear at Berlinale 2016. He is back in Venice, where he won the Golden Lion in 2013, this time turning his documentary camera on Syria.

Padrenostro (It) | Dir. Claudio Noce

Miss Marx (It-Bel) | Dir. Susanna Nicchiarelli

Italy’s Susanna Nicchiarelli won the Orizzonti Award in 2017 for her dazzling drama Nico 1988

Now in the main competition with an all star British cast she explore the life of Eleanor Marx daughter of the infamous Carl.

Pieces Of A Woman (Can-Hun) | Dir. Kornel Mandruczo

In his first English language film the Hungarian director who made his name with White Dog explores the emotional journey of a woman who has lost her child.

Sun Children (Iran) | Dir. Majid Majidi

The Tehran based director has already won plaudits for best script, production design and film for his latest drama that tackles the subject of child labour.

Wife Of A Spy (Jap) | Dir. Kiyoshi Kurosawa

A Japanese wife is saddled with the sins of her husband in this painterly portrait set in 1940s Japan from Kiyoshi Kurasawa (Creepy).

Dear Comrades (Rus) | Dir. Andrey Konchalovsky

The Russian director known for Postman’s White Nights (2014) and Paradise (2016) returns to Venice with his latest, a political drama based on real events in Novocherkassk 1962 when Soviet troops seeking to cover up mass labour strikes opened fire on workers and one in particular Lyudmila (Yuliya Vysotskaya).

Laila In Haifa (Isr-Fr) | Dir. Amos Gitai

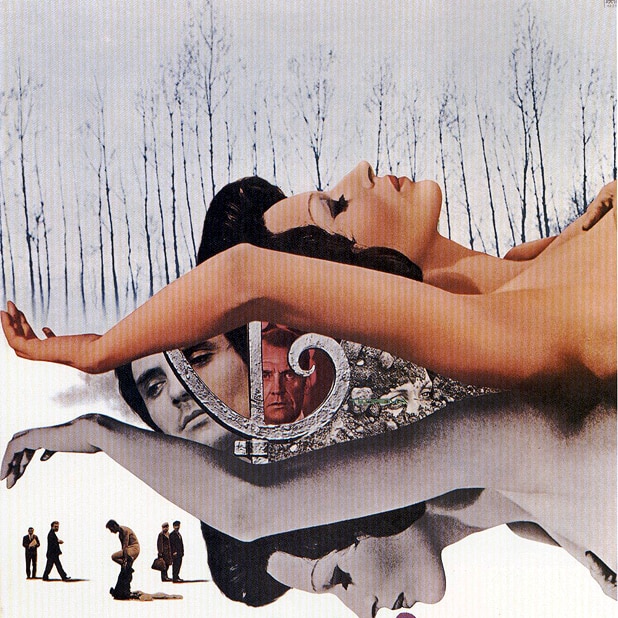

Lovers (Fr) | Dir. Nicole Garcia

Pierre Niney, Stacy Martin and Benoit Magimel star in this Noirish Parisian drama that sees a woman fall for her ex while on holiday with her husband.

Nuevo Orden (Mex-Fr) | Dir. Michel Franco

Franco loves exploring the psychology behind human relationships as he does here again in this latest that sees a high-society wedding gatecrashed by unwelcome guests.

The World To Come (US) | Dir. Mona Fastvold

Physical and emotional privation gives rise to a surprising love story in Norwegian filmmaker Mona Fastvold’s drama set in an US East Coast frontier town during the 1850s.

Le Sorelle Macaluso (It) | Dir. Emma Dante

In Between Dying (Az-US) | Dir. Hilal Baydarov

Out Of Competition – Drama

Lacci (It) – Opening Film | Dir. Daniele Luchetti

Mosquito State (Pol) | Dir. Filip Jan Rymsza

Night In Paradise (S Kor) | Dir. Park Hoon-Jung

The Duke (UK) | Dir. Roger Michell

Jim Broadbent and Helen Mirren lead a cast of Fionn Whitehead, Matthew Goode, Anna Maxwell Martin for this British drama based on the theft of Goya’s portrait of the Duke of Wellington from the National Gallery in London in 1961.

Assandira (It) | Dir. Salvatore Mereu

Love After Love (China) | Dir. Ann Hui

Mandibules (Fr-Bel) | Dir. Quentin Dupieux

Lasciami Andare (It) – Closing Film | Dir. Stafano Mordini

The Human Voice (approximately 30’) is a loose adaptation of the original stage play by Jean Cocteau, directed by Pedro Almodóvar and featuring Tilda Swinton as ‘the voice’. It tells the story of a jilted woman (Swinton), hoping her lover will get in touch. This is Pedro Almodóvar’s first time shooting in English. Alberto Iglesias composed the score.

One Night in Miami by Regina King

Set on the night of February 25, 1964, the story follows a young Cassius Clay (before he became Muhammad Ali) on the night her defeated Sonny Liston to win the title of World Heavyweight Boxing Champion. Clay – unable to stay on at the venue because of Jim Crow-era segregation laws – instead spends the night at the Hampton House Motel in one of Miami’s historically black neighbourhoods, celebrating with three of his closest friends: activist Malcolm X, singer Sam Cooke and football star Jim Brown. The next morning, the four men emerge determined to define a new world for themselves and their people. In One Night in Miami, Kemp Powers explores what happened during these pivotal hours through the dynamic relationship between the four men and the way their friendship, paired with their shared struggles, fueled their path to becoming the civil rights icons they are today.

Out Of Competition – Documentaries

Sportin’ Life (It) | Dir. Abel Ferrara

Crazy, Not Insane (US) | Dir. Alex Gibney

Greta (Swe) | Dir. Nathan Grossman

Salvatore – Shoemaker of Dreams (It) | Dir. Luca Guadagnino

Final Account (UK) | Dir. Luke Holland

Looking at the other side of the coin, Holland cobbles together interviews from those Nazis who perpetrated the Holocaust.

La Verita Su La Dolce Vita (It) | Dir. Giuseppe Pedersoli

Molecole (It) | Dir. Andrea Segre

Paolo Conte, Via Con Me (It) | Dir. Giorgio Verdelli

Narciso Em Ferias (Bra) | Dirs. Renato Terra, Ricardo Calil

Hopper/Welles (USA) | Dir. Orson Welles

Yes, another documentary about Orson Welles – can there ever be too many? This unscripted one captures a conversation between the maverick multi-talented Welles and the ingenu filmmaker Hopper that took place in 1971 over dinner, shooting the breeze over politics, personal issues and, or course, filmmaking. Made available courtesy of The Other Side of the Wind (Venice 2018) producer Filip Jan Rymsza.

City Hall (USA) | Dir. Frederick Wiseman

Out Of Competition – Special Screenings

Princesse Europe (Fra) | Dir. Camille Lotteau

30 Monedas – episode 1 (Spa) – series | Dir. Alex De La Iglesia

Orizzonti

Apples (Greece-Pol-Slovenia) – Opening Film | Dir. Christos Nikou

La Troisième Guerre (Fra) | Dir. Giovanni Aloi

Milestone (India) | Dir. Ivan Ayr

The Wasteland (Iran) | Dir. Ahmad Bahrami

The Man Who Sold His Skin | Dir. Kaouther Ben Hania

I Predatori (It) | Dir. Pietro Castellitto

Mainstream (USA) | Dir. Gia Coppola

Genus Pan (Phil) | Dir. Lav Diaz

Zanka Contact (Fr-Mor-Bel) | Dir. Ismael El Iraki

Guerra E Pace (It-Switz) | Dirs. Martina Parenti, Massimo D’Anolfi

La Buit Des Rois (Ivory Coast-Fr-Can) | Dir. Philippe Lacote

The Furnace (Aus) | Dir. Roderick Mackay

Careless Crime (Iran) | Dir. Shahram Mokri

Gaza Mon Amour | Dirs. Tarzan Nasser, Arab Nasser

Selva Tragica (Mex-Fr-Ger) | Dir. Yulene Olaizola

Nowhere Special (It-Rom-UK) | Dir. Uberto Pasolini

Listen (UK-Port) | Dir. Ana Rocha De Sousa

The Best Is Yet To Come (China) | Dir. Wang Jing

Yellow Cat (Kazakhstan-Fr) | Dir. Adilkhan Yerzhanov

VENICE FILM FESTIVAL 2-12 SEPTEMBER

Dir: Roman Polanski | Wri: Robert Harris | 122’

Dir: Roman Polanski | Wri: Robert Harris | 122’ Dir: Andrey A Tarkovskiy | Russia Doc 97’

Dir: Andrey A Tarkovskiy | Russia Doc 97’

The lineup for the 2018 BFI London Film Festival has been announced, and the public box office is open. The 12-day festival will show over 225 feature-length films from all over the globe – so here are some of the best we’ve seen from this year’s international festival circuit.

The lineup for the 2018 BFI London Film Festival has been announced, and the public box office is open. The 12-day festival will show over 225 feature-length films from all over the globe – so here are some of the best we’ve seen from this year’s international festival circuit.

WOMAN AT WAR (2018) – SACD Winner, Cannes Film Festival 2018

WOMAN AT WAR (2018) – SACD Winner, Cannes Film Festival 2018 THE FAVOURITE

THE FAVOURITE

DOGMAN Best Actor, Marcello Forte, Cannes 2018 | Palm Dog Winner 2018

DOGMAN Best Actor, Marcello Forte, Cannes 2018 | Palm Dog Winner 2018  MADELINE’S MADELINE

MADELINE’S MADELINE MUSEUM – Best Script Berlinale 2018

MUSEUM – Best Script Berlinale 2018 IN FABRIC

IN FABRIC THE WILD PEAR TREE – Palme d’Or, Cannes 2018

THE WILD PEAR TREE – Palme d’Or, Cannes 2018  THEY’LL LOVE ME WHEN I’M DEAD (2018)

THEY’LL LOVE ME WHEN I’M DEAD (2018) Alberto Barbera has announced a stunning line-up of highly anticipated new features and documentaries in celebration of this year’s 71st edition of Venice Film Festival which takes place on the Lido from 28 August until 8 September 2018. 30% of this year’s films are made by women which sounds more positive. Obviously the festival can only programme films offered for screening.

Alberto Barbera has announced a stunning line-up of highly anticipated new features and documentaries in celebration of this year’s 71st edition of Venice Film Festival which takes place on the Lido from 28 August until 8 September 2018. 30% of this year’s films are made by women which sounds more positive. Obviously the festival can only programme films offered for screening. The festival kicks off on the 28th with a remastered 1920 version of THE GOLEM – HOW HE CAME TO BE (ab0ve) complete with musical accompaniment. This year’s festival opening film is Damien Chazelle’s biopic of Neil Armstrong FIRST MAN. There are 21 features and documentaries in the main competition which boasts the latest films from Olivier Assayas (a publishing drama DOUBLE LIVES stars Juliette Binoche), Jacques Audiard (THE SISTERS BROTHERS), Joel and Ethan Coen’s 6-part Western THE BALLAD OF BUSTER SCRUGGS, Brady Corbet’smusical drama VOX LUX; Alfonso Cuaron with ROMA; Luca Guadagnino’s SUSPIRIA sees Tilda Swinton playing 3 parts; Mike Leigh (PETERLOO), Yorgos Lanthimos with an 18th drama entitled THE FAVOURITE; Carlos Reygadas joins from his usual Cannes slot; and Julian Schnabel will present AT ETERNITY’S GATE a drama attempting to get inside the head of Vincent Van Gogh. Not to mention Laszlo Nemes’ Budapest WW1 drama NAPSZÁLLTA, a much awaited second feature and follow up to his Oscar winning Son of Saul.

The festival kicks off on the 28th with a remastered 1920 version of THE GOLEM – HOW HE CAME TO BE (ab0ve) complete with musical accompaniment. This year’s festival opening film is Damien Chazelle’s biopic of Neil Armstrong FIRST MAN. There are 21 features and documentaries in the main competition which boasts the latest films from Olivier Assayas (a publishing drama DOUBLE LIVES stars Juliette Binoche), Jacques Audiard (THE SISTERS BROTHERS), Joel and Ethan Coen’s 6-part Western THE BALLAD OF BUSTER SCRUGGS, Brady Corbet’smusical drama VOX LUX; Alfonso Cuaron with ROMA; Luca Guadagnino’s SUSPIRIA sees Tilda Swinton playing 3 parts; Mike Leigh (PETERLOO), Yorgos Lanthimos with an 18th drama entitled THE FAVOURITE; Carlos Reygadas joins from his usual Cannes slot; and Julian Schnabel will present AT ETERNITY’S GATE a drama attempting to get inside the head of Vincent Van Gogh. Not to mention Laszlo Nemes’ Budapest WW1 drama NAPSZÁLLTA, a much awaited second feature and follow up to his Oscar winning Son of Saul. The out of competition selection is equally exciting and thematically rich. There is Bradley Cooper’s directing debut A STAR IS BORN (left), Charles Manson-themed CHARLIE SAYS from Mary Herron; Amos Gitai’s A TRAMWAY IN JERUSALEM, and Zhang Yimou’s YING (SHADOW). And those whose enjoyed S Craig Zahler’s dynamite Brawl in Cell Block 99 will be pleased to hear that his DRAGGED ACROSS CONCRETE adds Mel Gibson to the previous cast of Jennifer Carpenter and Vince Vaughn. There will be an historic epic set in the time of the French Revolution: UN PEUPLE ET SON ROI features Gaspart Ulliel and Denis Lavant (who also stars in Rick Alverson’s Golden Lion hopeful THE MOUNTAIN) , and Amir Naderi’s MAGIC LANTERN which has the wonderful English talents of Jacqueline Bisset. And talking of England, Mike Leigh’s much gloated over historical epic PETERLOO finally makes it to the competition line-up

The out of competition selection is equally exciting and thematically rich. There is Bradley Cooper’s directing debut A STAR IS BORN (left), Charles Manson-themed CHARLIE SAYS from Mary Herron; Amos Gitai’s A TRAMWAY IN JERUSALEM, and Zhang Yimou’s YING (SHADOW). And those whose enjoyed S Craig Zahler’s dynamite Brawl in Cell Block 99 will be pleased to hear that his DRAGGED ACROSS CONCRETE adds Mel Gibson to the previous cast of Jennifer Carpenter and Vince Vaughn. There will be an historic epic set in the time of the French Revolution: UN PEUPLE ET SON ROI features Gaspart Ulliel and Denis Lavant (who also stars in Rick Alverson’s Golden Lion hopeful THE MOUNTAIN) , and Amir Naderi’s MAGIC LANTERN which has the wonderful English talents of Jacqueline Bisset. And talking of England, Mike Leigh’s much gloated over historical epic PETERLOO finally makes it to the competition line-up